The London Beer Flood was an accident at Meux & Co's Horse Shoe Brewery, London, on 17 October 1814. It took place when one of the 22-foot-tall (6.7 m) wooden vats of fermenting porter burst. The escaping liquid dislodged the valve of another vessel and destroyed several large barrels: between 128,000 and 323,000 imperial gallons (580,000–1,470,000 L; 154,000–388,000 US gal) of beer were released in total.

The resulting wave of porter destroyed the back wall of the brewery and swept into an area of slum dwellings known as the St Giles rookery. Eight people were killed, five of them mourners at the wake being held by an Irish family for a two-year-old boy. The coroner's inquest returned a verdict that the eight had lost their lives "casually, accidentally and by misfortune".[1] The brewery was nearly bankrupted by the event; it avoided collapse after a rebate from HM Excise on the lost beer. The brewing industry gradually stopped using large wooden vats after the accident. The brewery moved in 1921, and the Dominion Theatre is now where the brewery used to stand. Meux & Co went into liquidation in 1961.

Background

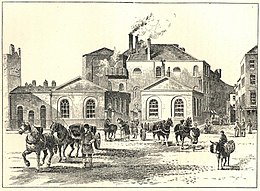

editIn the early nineteenth century the Meux Brewery was one of the two largest in London, along with Whitbread.[2] In 1809 Sir Henry Meux purchased the Horse Shoe Brewery, at the junction of Tottenham Court Road and Oxford Street.[3] Meux's father, Sir Richard Meux, had previously co-owned the Griffin Brewery in Liquor-Pond Street (now Clerkenwell Road), in which he had constructed the largest vat in London, capable of holding 20,000 imperial barrels.[4][a]

Henry Meux emulated his father's large vat,[4] and constructed a wooden vessel 22 feet (6.7 m) tall and capable of holding 18,000 imperial barrels.[b] Eighty long tons (eighty-one metric tons) of iron hoops were used to strengthen the vat.[5][6] Meux brewed only porter, a dark beer that was first brewed in London and was the most popular alcoholic drink in the capital.[7][8] Meux & Co brewed 102,493 imperial barrels in the twelve months up to July 1812.[9][c] Porter was left in the large vessels to mature for several months, or up to a year for the best quality versions.[8]

At the rear of the brewery ran New Street, a small cul-de-sac that joined on to Dyott Street;[d] this was within the St Giles rookery.[10][11][12] The rookery, which covered an area of eight acres (3.2 ha), "was a perpetually decaying slum seemingly always on the verge of social and economic collapse", according to Richard Kirkland, the professor of Irish literature.[13] Thomas Beames, the preacher of Westminster St James, and author of the 1852 work The Rookeries of London: Past, Present and Prospective, described the St Giles rookery as "a rendezvous of the scum of society";[14] the area had been the inspiration for William Hogarth's 1751 print Gin Lane.[15]

17 October 1814

editAt around 4:30 in the afternoon of 17 October 1814, George Crick, Meux's storehouse clerk, saw that one of the 700-pound (320 kg) iron bands around a vat had slipped. The 22-foot (6.7 m) tall vessel was filled to within four inches (ten centimetres) of the top with 3,555 imperial barrels of ten-month-old porter.[16][17][e] As the bands slipped off the vats two or three times a year, Crick was unconcerned. He told his supervisor about the problem, but was told "that no harm whatever would ensue".[18] Crick was told to write a note to Mr Young, one of the partners of the brewery, to have it fixed later.[19]

An hour after the hoop fell off, Crick was standing on a platform thirty feet (9.1 m) from the vat, holding the note to Mr Young, when the vessel, with no indication, burst.[20] The force of the liquid's release knocked the stopcock from a neighbouring vat, which also began discharging its contents; several hogsheads of porter were destroyed, and their contents added to the flood.[1][f] Between 128,000 and 323,000 imperial gallons[g] were released.[16][h] The force of the liquid destroyed the rear wall of the brewery; it was 25 feet (7.6 m) high and two and a half bricks thick.[20] Some of the bricks from the back wall were knocked upwards, and fell onto the roofs of the houses in the nearby Great Russell Street.[17]

A wave of porter some 15 feet (4.6 m) high swept into New Street, where it destroyed two houses[6][17] and badly damaged two others.[27][28] In one of the houses a four-year-old girl, Hannah Bamfield, was having tea with her mother and another child. The wave of beer swept the mother and the second child into the street; Hannah was killed.[i] In the second destroyed house, a wake was being held by an Irish family for a two-year-old boy; Anne Saville, the boy's mother, and four other mourners (Mary Mulvey and her three-year-old son, Elizabeth Smith and Catherine Butler) were killed.[29] Eleanor Cooper, a 14-year-old servant of the publican of the Tavistock Arms in Great Russell Street, died when she was buried under the brewery's collapsed wall while washing pots in the pub's yard.[1] Another child, Sarah Bates, was found dead in another house in New Street.[30] The land around the building was low-lying and flat. With insufficient drainage, the beer flowed into cellars, many of which were inhabited, and people were forced to climb on furniture to avoid drowning.[17][31]

All those in the brewery survived, although three workmen had to be rescued from the rubble;[1][16] the superintendent and one of the workers were taken to Middlesex Hospital, along with three others.[19][22]

17 to 19 October

editStories later arose of hundreds of people collecting the beer, mass drunkenness and a death from alcohol poisoning a few days later.[32] The brewing historian Martyn Cornell states that newspapers of the time made no reference to the revelry, or of the later death; instead, the newspapers reported that the crowds were well-behaved.[23] Cornell points out that the popular press of the time did not like the immigrant Irish population that lived in St Giles, so if there had been any misbehaviour, it would have been reported.[6]

The area surrounding the rear of the brewery showed a "scene of desolation [that] presents a most awful and terrific appearance, equal to that which fire or earthquake may be supposed to occasion".[33] Watchmen at the brewery charged people to view the remains of the destroyed beer vats, and several hundred spectators came to view the scene.[23] The mourners killed in the cellar were given their own wake at The Ship public house in Bainbridge Street. The other bodies were laid out in a nearby yard by their families; the public came to see them and donated money for their funerals.[17] Collections were taken up more widely for the families.[34]

Coroner's inquest

editThe coroner's inquest was held at the Workhouse of the St Giles parish on 19 October 1814; George Hodgson, the coroner for Middlesex, oversaw proceedings.[35] The details of the victims were read out as:

- Eleanor Cooper, age 14

- Mary Mulvey, age 30

- Thomas Murry, age 3 (Mary Mulvey's son)

- Hannah Bamfield, age 4 years 4 months

- Sarah Bates, age 3 years 5 months

- Ann Saville, age 60

- Elizabeth Smith, age 27

- Catherine Butler, age 65.[1]

Hodgson took the jurors to the scene of the events, and they viewed the brewery and bodies before evidence was taken from witnesses.[35] The first witness was George Crick, who had seen the event happen in full; his brother was one of the men who had been injured at the brewery. Crick said that hoops on the vats failed three or four times a year, but without any previous problems. Accounts were also heard from Richard Hawse—the landlord of the Tavistock Arms, whose barmaid had been killed in the accident—and several others. The jury returned a verdict that the eight had lost their lives "casually, accidentally and by misfortune".[1][35]

Later

editAs the coroner's inquest reached a verdict of an act of God, Meux & Co did not have to pay compensation.[17] Nevertheless, the disaster—the lost porter, the damage to the buildings and the replacement of the vat—cost the company £23,000. After a private petition to Parliament they recovered about £7,250 from HM Excise, saving them from bankruptcy.[3][j]

The Horse Shoe Brewery went back into business soon afterwards,[23] but closed in 1921 when Meux moved their production to the Nine Elms brewery in Wandsworth, which they had purchased in 1914.[37] At the time of its closure the site covered 103,000 square feet (9,600 m2).[38] The brewery was demolished the following year and the Dominion Theatre was later built on the site.[16][39] Meux & Co went into liquidation in 1961.[37] As a result of the accident, large wooden tanks were phased out across the brewing industry and replaced with lined concrete vessels.[16][25]

See also

editNotes and references

editNotes

edit- ^ 20,000 imperial barrels equates to 3,300,000 L; 720,000 imp gal; 860,000 US gal.

- ^ 18,000 imperial barrels equates to 2,900,000 L; 650,000 imp gal; 780,000 US gal

- ^ 102,493 imperial barrels equates to 16,774,000 L; 3,690,000 imp gal; 4,431,000 US gal.

- ^ New Street was demolished as part of redevelopment in the twentieth century; Dyott Street still runs along approximately the same course.[10][11]

- ^ 3,555 imperial barrels equates to 581,800 L; 128,000 imp gal; 153,700 US gal.

- ^ A hogshead equates to 54 imperial gallons.[21]

- ^ 128,000 to 323,000 imperial gallons equates to 580,000–1,470,000 L; 1,020,000–2,580,000 imp pt; 154,000–388,000 US gal.

- ^ Sources disagree on the amount of beer released. Figures include:

- ^ Both Mrs Bamfield and the second child spent time in hospital in a critical condition, but later recovered.[1]

- ^ £23,000 in 1814 equates to approximately £2,032,000 in 2023; £7,250 in 1814 equates to approximately £641,000 in 2023, according to calculations based on the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[36]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g "Dreadful Accident at H Meux & Co's Brewhouse". The Times.

- ^ Henderson 2005, p. 148.

- ^ a b Hornsey 2007, p. 450.

- ^ a b Glover 2012, Chapter 27.

- ^ Brinch Kissmeyer & Garrett 2012, p. 348.

- ^ a b c d Eschner 2017.

- ^ Hornsey 2007, pp. 486–487.

- ^ a b Dornbusch & Garrett 2012, p. 662.

- ^ Overall 1870, p. 74.

- ^ a b "UCL Bloomsbury Project: Dyott Street". University College London.

- ^ a b "UCL Bloomsbury Project: New Street". University College London.

- ^ Mayhew 1862, p. 299.

- ^ Kirkland 2012, p. 16.

- ^ Beames 1852, p. 19.

- ^ Beames 1852, p. 24.

- ^ a b c d e f "The London Beer Flood". The History Press.

- ^ a b c d e f Klein 2014.

- ^ "Dreadful Accident at H. Meux & Co's Brewhouse". Caledonian Mercury.

- ^ a b "Dreadful Accident at Meux & Co's Brewhouse". London Courier and Evening Gazette.

- ^ a b "Accident at Meux's Brewhouse". Morning Chronicle.

- ^ Foster 1992, p. 14.

- ^ a b Makepeace 2015.

- ^ a b c d Tingle 2014.

- ^ Overall 1870, p. 75.

- ^ a b Johnson, Historic UK.

- ^ Clarkson 2014, p. 1005.

- ^ Cornell 2010, p. 61.

- ^ "Dreadful Accident". Evening Mail.

- ^ "The Catastrophe at Mr Meux's". Morning Post (20 October).

- ^ "The Catastrophe at Mr Meux's". Morning Post (21 October).

- ^ "Dreadful Catastrophe at Meux & Co's Brewhouse". Northampton Mercury.

- ^ "A real beer tsunami" Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ "Dreadful Accident". Morning Post.

- ^ Urban 1814, p. 390.

- ^ a b c "Coroner's Inquest". Kentish Gazette.

- ^ Clark 2018.

- ^ a b Richmond & Turton 1990, p. 233.

- ^ "The Estate Market". The Times.

- ^ Protz 2012, p. 583.

Sources

editBooks

edit- Beames, Thomas (1852). The Rookeries of London: Past, Present and Prospective. London: T. Bosworth. OCLC 828478078.

- Brinch Kissmeyer, Anders; Garrett, Oliver (2012). "Fermentation vessels". In Garrett, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Beer. New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195367133.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-536713-3.

- Clarkson, Janet (2014). Food History Almanac: Over 1,300 Years of World Culinary History, Culture and Social Influence. Lanham, MA: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-2715-6.

- Cornell, Martyn (2010). Amber, Gold and Black: The History of Britain's Great Beers. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-5567-9.

- Dornbusch, Horst; Garrett, Oliver (2012). "Porter". In Garrett, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Beer. New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195367133.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-536713-3.

- Foster, Terry (1992). Porter. Boulder, CO: Brewers Publications. ISBN 978-0-9373-8128-1.

- Glover, Brian (2012). The Lost Beers & Breweries of Britain. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-4456-2049-7.

- Henderson, W. O. (2005). Industrial Britain Under the Regency, 1814–18: The Diaries of Escher, Bodmer, May And De Gallois 1814–18. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-38220-5.

- Hornsey, Ian S. (2007). A History of Beer and Brewing. London: Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 978-1-84755-002-6.

- Mayhew, Henry (1862). London Labour and the London Poor. Vol. 4. London: Charles Griffin & Co. OCLC 633789935.

- Overall, William Henry (1870). The Dictionary of Chronology, Or Historical and Statistical Register. London: W. Tegg.

- Protz, Roger (2012). Oliver, Garrett (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Beer. New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195367133.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-536713-3.

- Richmond, Lesley; Turton, Alison (1990). The Brewing Industry: A Guide to Historical Records. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-3032-1.

Journals

edit- Kirkland, Richard (Spring 2012). "Reading the Rookery: The Social Meaning of an Irish Slum in Nineteenth-Century London". New Hibernia Review / Iris Éireannach Nua. 16 (1): 16–30. doi:10.1353/nhr.2012.0000. JSTOR 23266637. S2CID 144980722.

Newspapers

edit- "Accident at Meux's Brewhouse". Morning Chronicle. 20 October 1814. p. 3.

- "Coroner's Inquest". Kentish Gazette. 25 October 1814. p. 3.

- "Dreadful Accident". Morning Post. 19 October 1814. p. 3.

- "The Catastrophe at Mr Meux's". Morning Post. 20 October 1814. p. 3.

- "The Catastrophe at Mr Meux's". Morning Post. 21 October 1814. p. 3.

- "Dreadful Accident". Evening Mail. 19 October 1814. p. 3.

- "Dreadful Accident at H. Meux & Co's Brewhouse". Caledonian Mercury. 24 October 1814. p. 2.

- "Dreadful Accident at Meux & Co's Brewhouse". London Courier and Evening Gazette. 20 October 1814. p. 2.

- "Dreadful Accident at H. Meux & Co's Brewhouse". The Times. 20 October 1814. p. 3.

- "Dreadful Catastrophe at Meux & Co's Brewhouse". Northampton Mercury. 22 October 1814. p. 3.

- "The Estate Market". The Times. 23 February 1922. p. 22.

- Tingle, Rory (17 October 2014). "What really happened in the London Beer Flood 200 years ago?". The Independent.

- Urban, Sylvanus (1814). The Gentleman's Magazine: And Historical Chronicle. From July To December 1814. Vol. LXXXIV. London: Nichols.

Internet

edit- Clark, Gregory (2018). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- "'A real beer tsunami'. Remembering the big British beer flood of October, 1814 with brewing historian Martyn Cornell". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 17 October 2014. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- Eschner, Kat (4 August 2017). "This 1814 Beer Flood Killed Eight People". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- Johnson, Ben. "The London Beer Flood of 1814". Historic UK. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- Klein, Christopher (17 October 2014). "The London Beer Flood". History.com. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- "The London Beer Flood". The History Press. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- Makepeace, Margaret (17 October 2015). "The London Beer Flood 1814 – Untold lives blog". British Library. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- "UCL Bloomsbury Project: Dyott Street". University College London. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- "UCL Bloomsbury Project: New Street". University College London. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

51°31′01″N 00°07′48″W / 51.51694°N 0.13000°W