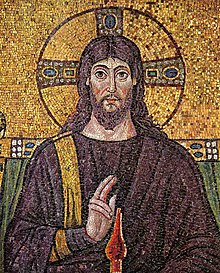

The messiah complex is a mental state in which a person believes they are a messiah or prophet and will save or redeem people in a religious endeavour.[1][2] The term can also refer to a state of mind in which an individual believes that they are responsible for saving others.

Religious delusion

editThe term messiah complex is not addressed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), as it is not a clinical term nor diagnosable disorder. However, the symptoms as a proposed disorder closely resemble those found in individuals with delusions of grandeur or with grandiose self-images that veer towards the delusional.[3] An account specifically identified it as a category of religious delusion, which pertains to strong fixed beliefs that cause distress or disability. It is the type of religious delusion that is classified as grandiose while the other two categories are persecutory and belittled.[4] According to philosopher Antony Flew, an example of this type of delusion was the case of Paul, who declared that God spoke to him, telling him that he would serve as a conduit for people to change.[5] The Kent–Flew thesis argued that his experience entailed auditory and visual hallucinations.[5]

Examples

editIn terms of the attitude wherein an individual sees themselves as having to save another or a group of poor people, there is the notion that the action inflates their own sense of importance and discounts the skills and abilities of the people they are helping to improve their own lives.[6]

The messiah complex is most often reported in patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. When a messiah complex is manifested within a religious individual after a visit to Jerusalem, it may be identified as a psychosis known as Jerusalem syndrome.[7]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Messiah Complex Psychology". flowpsychology.com. 11 February 2014. Archived from the original on 21 March 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ^ Kelsey, Darren (2017). Media and Affective Mythologies: Discourse, Archetypes and Ideology in Contemporary Politics. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 155. ISBN 978-3319607580.

- ^ Haycock, Dean (2016). Characters on the Couch: Exploring Psychology through Literature and Film: Exploring Psychology through Literature and Film. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 151. ISBN 978-1440836985.

- ^ Clarke, Isabel (2010). Psychosis and Spirituality: Consolidating the New Paradigm (2d ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. p. 240. ISBN 978-0470683484.

- ^ a b Habermas, Gary; Flew, Antony (2005). Resurrected?: An Atheist and Theist Dialogue. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 9. ISBN 0742542254.

- ^ Corbett, Steve; Fikkert, Brian (2014). Helping Without Hurting in Short-Term Missions: Leader's Guide. Moody Publishers. ISBN 978-0802491886.[page needed]

- ^ "Dangerous delusions: The Messiah Complex and Jerusalem Syndrome". Freethought Nation. Archived from the original on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2015.