The mitochondrial theory of ageing has two varieties: free radical and non-free radical. The first is one of the variants of the free radical theory of ageing. It was formulated by J. Miquel and colleagues in 1980[1] and was developed in the works of Linnane and coworkers (1989).[2] The second was proposed by A. N. Lobachev in 1978.[3]

The mitochondrial free radical theory of ageing (MFRTA) proposes that free radicals produced by mitochondrial activity damage cellular components, leading to ageing.

Mitochondria are cell organelles which function to provide the cell with energy by producing ATP (adenosine triphosphate). During ATP production electrons can escape the mitochondrion and react with water, producing reactive oxygen species, ROS for short. ROS can damage macromolecules, including lipids, proteins and DNA, which is thought to facilitate the process of ageing.

In the 1950s Denham Harman proposed the free radical theory of ageing, which he later expanded to the MFRTA.

When studying the mutations in antioxidants, which remove ROS, results were inconsistent. However, it has been observed that overexpression of antioxidant enzymes in yeast, worms, flies and mice were shown to increase lifespan.

Molecular basis

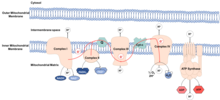

editMitochondria are thought to be organelles that developed from endocytosed bacteria which learned to coexist inside ancient cells. These bacteria maintained their own DNA, the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which codes for components of the electron transport chain (ETC). The ETC is found in the inner mitochondrial membrane and functions to transfer energy derived from food into ATP molecules. The process is called oxidative phosphorylation, because ATP is produced from ADP in a series of redox reactions. Electrons are transferred through the ETC from NADH and FADH2 to oxygen, reducing oxygen to water.

ROS

editROS are highly reactive, oxygen-containing chemical species, which include superoxide, hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radical. If the complexes of the ETC do not function properly, electrons can leak and react with water, forming ROS. Normally leakage is low and ROS is kept at physiological levels, fulfilling roles in signaling and homeostasis. In fact, their presence at low levels lead to increased life span, by activating transcription factors and metabolic pathways involved in longevity. At increased levels ROS cause oxidative damage by oxidizing macromolecules, such as lipids, proteins and DNA. This oxidative damage to macromolecules is thought to be the cause of ageing. Mitochondrial DNA is especially susceptible to oxidative damage, due to its proximity to the site of production of these species.[4] Damaging of mitochondrial DNA causes mutations, leading to production of ETC complexes, which do not function properly, increasing ROS production, increasing oxidative damage to macromolecules.

UPRmt

editThe mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt) is turned on in response to mitochondrial stress. Mitochondrial stress occurs when the proton gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane is dissipated, mtDNA is mutated, and/or ROS accumulates, which can lead to misfolding and reduced function of mitochondrial proteins. Stress is sensed by the nucleus, where chaperones and proteases are upregulated, which can correct folding or remove damaged proteins, respectively.[5] Decrease in protease levels are associated with ageing, as mitochondrial stress will remain, maintaining high ROS levels.[6] Such mitochondrial stress and dysfunction has been linked to various age-associated diseases, including cardiovascular diseases, and type-2 diabetes.[7]

Mitochondrial metabolites

editAs the mitochondrial matrix is where the TCA cycle takes place, different metabolites are commonly confined to the mitochondria. Upon ageing, mitochondrial function declines, allowing escape of these metabolites, which can induce epigenetic changes,[8] associated with ageing.

Acetyl-coenzyme A (Acetyl-CoA) enters the TCA cycle in the mitochondrial matrix, and is oxidized in the process of energy production. Upon escaping the mitochondria and entering the nucleus, it can act as a substrate for histone acetylation.[9] Histone acetylation is an epigenetic modification, which leads to gene activation. At a young age, acetyl-CoA levels are higher in the nucleus and cytosol, and its transport to the nucleus can extend lifespan in worms.[10][11]

Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (NAD+) is produced in the mitochondria and upon escaping to the nucleus, can act as a substrate for sirtuins.[12] Sirtuins are family of proteins, known to play a role in longevity. Cellular NAD+ levels have been shown to decrease with age.[13]

DAMPs

editDamage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) are molecules that are released during cell stress. Mitochondrial DNA is a DAMP, which only becomes available during mitochondrial damage. Blood mitochondrial DNA levels become elevated with age, contributing to inflamm-ageing, a chronic state of inflammation characteristic of advanced age.[14]

Mitochondrial-derived peptides

editMitochondrial DNA has been known to encode 13 proteins. Recently, other short protein coding sequences have been identified, and their products are referred to as mitochondria-derived peptides.[15]

The mitochondrial-derived peptide, humanin has been shown to protect against Alzheimer's disease, which is considered an age-associated disease.[16]

MOTS-c has been shown to prevent age-associated insulin resistance, the main cause of type 2 diabetes.

Humanin and MOTS-c levels have been shown to decline with age, and their activity seems to increase longevity.[17]

Mitochondrial membrane

editAlmaida-Pagan and coworkers found that mitochondrial membrane lipid composition changes with age, when studying Turquoise killifish.[18] The proportion of monounsaturated fatty acids and the overall phospholipid content decreased with age.

History

editIn 1956 Denham Harman first postulated the free radical theory of ageing, which he later modified to the mitochondrial free radical theory of ageing (MFRTA).[19] He found ROS as the main cause of damage to macromolecules, known as "ageing". He later modified his theory because he found that mitochondria were producing and being damaged by ROS, leading him to the conclusion that mitochondria determine ageing. In 1972, he published his theory in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society.[20]

Evidence

editIt has been observed that with age, mitochondrial function declines and mitochondrial DNA mutation increases in tissue cells in an age-dependent manner. This leads to increase in ROS production and potential decrease in the cell's ability to remove ROS. Most long-living animals have been shown to be more resistant to oxidative damage and have lower ROS production, linking ROS levels to lifespan.[21][22][23][24][25] Overexpression of antioxidants, which reduce ROS, has also been shown to increase lifespan.[26][27] Bioinformatics analysis showed that amino acid composition of mitochondrial proteins correlate with longevity (long-living species are depleted in cysteine and methionine), linking mitochondria to the process of ageing.[28][29] By studying expression of certain genes in C. elegans,[30] Drosophila,[31] and mice [32] it was found that disruption of ETC complexes can extend life – linking mitochondrial function to the process of ageing.

Evidence supporting the theory started to crumble in the early 2000s. Mice with reduced expression of the mitochondrial antioxidant, SOD2, accumulated oxidative damage and developed cancer, but did not age faster.[33] Overexpression of antioxidants reduced cellular stress, but did not increase mouse life span.[34][35] The naked mole-rat, which lives 10-times longer than normal mice, has been shown to have higher levels of oxidative damage.[36]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Miquel, J.; Economos, A. C.; Fleming, J.; Johnson, J. E. (1980-01-01). "Mitochondrial role in cell aging". Experimental Gerontology. 15 (6): 575–591. doi:10.1016/0531-5565(80)90010-8. ISSN 0531-5565. PMID 7009178. S2CID 38511082.

- ^ Linnane, AnthonyW; Ozawa, Takayuki; Marzuki, Sangkot; Tanaka, Masashi (1989-03-25). "Mitochondrial DNA Mutations as an Important Contributor to Ageing and Degenerative Diseases". The Lancet. 333 (8639): 642–645. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(89)92145-4. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 2564461. S2CID 11933110.

- ^ Lobachev A.N.Role of mitochondrial processes in the development and aging of organism. Aging and cancer (PDF), Chemical abstracts. 1979 v. 91 N 25 91:208561v.Deposited Doc., VINITI 2172-78, 1978, p. 48

- ^ Kowald; Kirkwood (2018). "Resolving the Enigma of the Clonal Expansion of mtDNA Deletions". Genes (Basel). 9 (3): 126. doi:10.3390/genes9030126. PMC 5867847. PMID 29495484.

- ^ Nargund; et al. (2015). "Mitochondrial and nuclear accumulation of the transcription factor ATFS-1 promotes OXPHOS recovery during the UPR(mt)". Molecular Cell. 58 (1): 123–133. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2015.02.008. PMC 4385436. PMID 25773600.

- ^ Bota; et al. (2005). "Downregulation of the human Lon protease impairs mitochondrial structure and function and causes cell death". Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 38 (1): 665–677. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.11.017. PMID 15683722. S2CID 32448357.

- ^ Kim; Wei; Sowers (2008). "Role of mitochondrial dysfunction in insulin resistance". Circulation Research. 102 (4): 401–414. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.165472. PMC 2963150. PMID 18309108.

- ^ Frezza (2017). "Mitochondrial metabolites: undercover signalling molecules". Interface Focus. 7 (2): 20160100. doi:10.1098/rsfs.2016.0100. PMC 5311903. PMID 28382199.

- ^ Menzies; Zhang; Katsuyaba; Auwerx (2016). "Protein acetylation in metabolism - metabolites and cofactors". Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 12 (1): 43–60. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2015.181. PMID 26503676. S2CID 19151622.

- ^ Shi; Tu (2015). "Acetyl-CoA and the regulation of metabolism: mechanisms and consequences". Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 33: 125–131. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2015.02.003. PMC 4380630. PMID 25703630.

- ^ Benayoun; Pollina; Brunet (2015). "Epigenetic regulation of ageing: linking environmental inputs to genomic stability". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 16 (1): 593–610. doi:10.1038/nrm4048. PMC 4736728. PMID 26373265.

- ^ Imai; Guarente (2016). "It takes two to tango: NAD+ and sirtuins in aging/longevity control". npj Aging and Mechanisms of Disease. 2: 16017. doi:10.1038/npjamd.2016.17. PMC 5514996. PMID 28721271.

- ^ Schultz; Sinclair (2016). "Why NAD(+) Declines during Aging: It's Destroyed". Cell Metabolism. 23 (6): 965–966. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.022. PMC 5088772. PMID 27304496.

- ^ Pinti; et al. (2014). "Circulating mitochondrial DNA increases with age and is a familiar trait: Implications for "inflamm-aging"". European Journal of Immunology. 44 (5): 1552–1562. doi:10.1002/eji.201343921. PMID 24470107. S2CID 5407086.

- ^ Kim; et al. (2017). "Mitochondrially derived peptides as novel regulators of metabolism". The Journal of Physiology. 595 (21): 6613–6621. doi:10.1113/JP274472. PMC 5663826. PMID 28574175.

- ^ Kim; et al. (2017). "Mitochondrially derived peptides as novel regulators of metabolism". The Journal of Physiology. 595 (21): 6613–6621. doi:10.1113/JP274472. PMC 5663826. PMID 28574175.

- ^ Kim; et al. (2017). "Mitochondrially derived peptides as novel regulators of metabolism". Journal of Physiology. 595 (21): 6613–6621. doi:10.1113/JP274472. PMC 5663826. PMID 28574175.

- ^ Almaida-Pagan; et al. (2019). "Age-related changes in mitochondrial membrane composition of Nothobranchius furzeri.: comparison with a longer-living Nothobranchius species". Biogerontology. 20 (1): 83–92. doi:10.1007/s10522-018-9778-0. PMID 30306289. S2CID 254287563.

- ^ Harman (1956). "Aging: a theory based on free radical and radiation chemistry". Journal of Gerontology. 11 (3): 298–300. doi:10.1093/geronj/11.3.298. hdl:2027/mdp.39015086547422. PMID 13332224.

- ^ Harman (1972). "A biologic clock: the mitochondria?". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 20 (4): 145–147. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1972.tb00787.x. PMID 5016631. S2CID 396830.

- ^ Martin; et al. (1996). "Genetic analysis of ageing: role of oxidative damage and environmental stresses". Nature Genetics. 13 (1): 25–34. doi:10.1038/ng0596-25. PMID 8673100. S2CID 9358797.

- ^ Liang; et al. (2003). "Genetic mouse models of extended lifespan". Experimental Gerontology. 38 (11–12): 1353–1364. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2003.10.019. PMID 14698816. S2CID 136263.

- ^ Lambert; et al. (2007). "Low rates of hydrogen peroxide production by isolated heart mitochondria associate with long maximum lifespan in vertebrate homeotherms". Aging Cell. 6 (5): 607–618. doi:10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00312.x. PMID 17596208. S2CID 22676318.

- ^ Ungvari; et al. (2011). "Extreme longevity is associated with increased resistance to oxidative stress in Arctica islandica, the longest-living non-colonial animal". The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 66 (7): 741–750. doi:10.1093/gerona/glr044. PMC 3143345. PMID 21486920.

- ^ Barja; et al. (2014). "The mitochondrial free radical theory of aging". Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science. 127: 1–27. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-394625-6.00001-5. ISBN 9780123946256. PMID 25149212.

- ^ Sun; et al. (2002). "Induced overexpression of mitochondrial Mn-superoxide dismutase extends the life span of adult Drosophila melanogaster". Genetics. 161 (2): 661–672. doi:10.1093/genetics/161.2.661. PMC 1462135. PMID 12072463.

- ^ Orr; Sohal (1994). "Extension of life-span by overexpression of superoxide dismutase and catalase in Drosophila melanogaster". Science. 263 (5150): 1128–30. Bibcode:1994Sci...263.1128O. doi:10.1126/science.8108730. PMID 8108730.

- ^ Moosmann; Behl (2008). "Mitochondrially encoded cysteine predicts animal lifespan". Aging Cell. 7 (1): 32–46. doi:10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00349.x. PMID 18028257.

- ^ Aledo; et al. (2011). "Mitochondrially encoded methionine is inversely related to longevity in mammals". Aging Cell. 10 (2): 198–207. doi:10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00657.x. PMID 21108730.

- ^ Rea; et al. (2007). "Relationship between mitochondrial electron transport chain dysfunction, development, and life extension in Caenorhabditis elegans". PLOS Biology. 5 (10): e259. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050259. PMC 1994989. PMID 17914900.

- ^ Copeland; et al. (2009). "Extension of Drosophila life span by RNAi of the mitochondrial respiratory chain". Current Biology. 19 (19): 1591–1598. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.08.016. PMID 19747824.

- ^ Liu; et al. (2005). "Evolutionary conservation of the clk-1-dependent mechanism of longevity: loss of mclk1 increases cellular fitness and lifespan in mice". Genes & Development. 19 (20): 2424–2434. doi:10.1101/gad.1352905. PMC 1257397. PMID 16195414.

- ^ Van Remmen; et al. (2003). "Life-long reduction in MnSOD activity results in increased DNA damage and higher incidence of cancer but does not accelerate aging". Physiological Genomics. 16 (1): 29–37. doi:10.1152/physiolgenomics.00122.2003. PMID 14679299. S2CID 9159294.

- ^ Huang; et al. (2000). "Ubiquitous overexpression of CuZn superoxide dismutase does not extend life span in mice". The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 55 (1): B5-9. doi:10.1093/gerona/55.1.b5. PMID 10719757.

- ^ Pérez; et al. (2009). "Is the oxidative stress theory of aging dead?". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects. 1790 (10): 1005–1014. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.06.003. PMC 2789432. PMID 19524016.

- ^ Andziak; et al. (2006). "High oxidative damage levels in the longest-living rodent, the naked mole-rat". Aging Cell. 5 (6): 463–471. doi:10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00237.x. PMID 17054663.