Nakalipithecus nakayamai, sometimes referred to as the Nakali ape,[1] is an extinct species of great ape from Nakali, Kenya, from about 9.9–9.8 million years ago during the Late Miocene. It is known from a right jawbone with 3 molars and from 11 isolated teeth. The jawbone specimen is presumed female as the teeth are similar in size to those of female gorillas and orangutans. Compared to other great apes, the canines are short, the enamel is thin, and the molars are flatter. Nakalipithecus seems to have inhabited a sclerophyllous woodland environment.

| Nakalipithecus Temporal range: Tortonian,

| |

|---|---|

| |

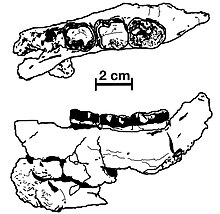

| Top and side views of the Nakalipithecus holotype, a jawbone and the molars | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Superfamily: | Hominoidea |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Genus: | †Nakalipithecus Kunimatsu et al., 2007 |

| Species: | †N. nakayamai

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Nakalipithecus nakayamai Kunimatsu et al., 2007

| |

Taxonomy

edit| Hominidae | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Two hypotheses on Nakalipithecus taxonomy[2] |

Nakalipithecus was first described from a right jawbone, the holotype KNM-NA46400, and eleven isolated teeth excavated in 2005 by a team of Japanese and Kenyan researchers in mud flow deposits in the Nakali area of northern Kenya's former Rift Valley Province, hence the genus name Nakalipithecus ("Nakali ape"). The species name is in honour of the late Japanese geologist Katsuhiro Nakayama who worked on the expedition. The specimen dates to about 9.9–9.8 million years ago in the Late Miocene. The specimens are housed by the National Museums of Kenya. The holotype preserves all 3 lower molars, and the isolated teeth are: a left first incisor, a right first incisor, a right canine, a right third upper premolar, a left third upper premolar, a right left fourth upper premolar, a left fourth upper premolar, a right first upper molar, a right third upper molar, a left third upper molar, and a left fourth lower premolar.[3]

It is debated if great apes evolved in Africa or Eurasia given the abundance of early fossil apes species in the latter and the paucity in the former, despite all modern great apes except the orangutan being known from Africa. The first Miocene African ape, Samburupithecus, was discovered in 1982.[4] It is unclear how Nakalipithecus is related to other apes. It is possible these Late Miocene African apes were stem great apes closely related to the last common ancestor of all modern African apes, which existed about 9–8 million years ago.[3]

Nakalipithecus and the 9 million year old Greek Ouranopithecus macedoniensis exhibit many similarities with each other, but Nakalipithecus has more basal (primitive) traits, which could indicate that it was the ancestor or closely related to the ancestor of Ouranopithecus. Ouranopithecus, in turn, is postulated to be closely related to australopithecines and the human line. This would show that apes evolved in Africa. However, evidence of common ancestry can also be interpreted as convergent evolution, with similar dental adaptations caused by inhabiting a similar environment, though Ouranopithecus seems to have consumed more hard objects than Nakalipithecus.[3] A 2017 study on deciduous fourth premolars—deciduous teeth are less affected by environmental factors as they soon fall out and are replaced by permanent teeth—found that Nakalipithecus and later African apes (including australopithecines) shared more similarities with each other than to Eurasian apes, though drew no clear conclusion on the Nakalipithecus–Ouranopithecus relationship.[5]

Nakalipithecus has also been proposed to have been the ancestor to the 8 million year old Chororapithecus, which possibly represents an early member of the gorilla line; if both of these are correct, then Nakalipithecus could potentially represent an early gorilla.[2]

Anatomy

editNakalipithecus has an overall large size, with teeth similar in size to those of female gorillas and orangutans. The specimen is thus presumed female. The Samburupithecus specimen was also about the same size. Unlike other apes, the canines are short, and as long as they are wide—about 10.7 mm × 10.5 mm (0.42 in × 0.41 in) in height and width respectively. For comparison, the left first incisor is 10.8 mm × 8.6 mm (0.43 in × 0.34 in). The premolars are elongated, and the protoconid (the cusp on the tongue side) of the third premolar is oriented more cheekwards, which is a distinguishing characteristic of Miocene African apes from Miocene Eurasian apes. Compared to African apes contemporary with Nakalipithecus, the tooth enamel on the molars is thinner, and the cusps (which project outward from the tooth) are less inflated, creating a wider basin. In the holotype, the first, second, and third molars are 15.6 mm × 14 mm (0.61 in × 0.55 in), 16.2 mm × 15.8 mm (0.64 in × 0.62 in), and 19.5 mm × 15.1 mm (0.77 in × 0.59 in), respectively. Like modern and some contemporary apes, but unlike earlier East African apes, the first molar is relatively large, with a first molar to second molar ratio of 85%. Like Ouranopithecus and early Sivapithecus (Sivapithecus is known from the Indian subcontinent), but unlike most contemporary and future apes, the third molar was much larger than the second, with a third molar to second molar ratio of 115%, though this ratio is smaller than that of the later Southeast Asian Khoratpithecus. The mandible is less robust (heavily built) than those of contemporary Eurasian Miocene apes, except for Ouranopithecus.[3]

Palaeobiology

editDuring the Late Miocene, East Africa, the Sahara, the Middle East, and Southern Europe all appear to have been predominantly seasonal sclerophyllous evergreen woodland environments. Nakali appears to have been dominated by C3 (forest) plants. Nakalipithecus is known from the Upper Beds, which comprise lakeside or riverine deposits.[3] Climate change caused the expansion of grasslands in Africa from 10–7 million years ago, likely fragmenting populations of forest-dwelling primates, leading to extinction.[6]

Nakali has also yielded a black rhino specimen,[7] the pig Nyanzachoerus, an antelope, the hippo Kenyapotamus, the rhino Kenyatherium, the giraffe Palaeotragus,[8] the horse Hipparion,[9] the elephant-like proboscideans Deinotherium and (possibly) Choerolophodon,[8] and the colobine monkey Microcolobus.[10] The third premolar of a small nyanzapithecine ape was also found in Nakali,[11][6] and Samburupithecus was nearly contemporaneous with Nakalipithecus, and was discovered 60 km (37 mi) to the north of Nakali.[3]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Kiarie, Maina. "Nakalipithecus". Enzi Museum. Retrieved 8 August 2023.

- ^ a b Katoh, S.; Beyene, Y.; Itaya, T.; et al. (2016). "New geological and palaeontological age constraint for the gorilla–human lineage split". Nature. 530 (7589): 215–218. Bibcode:2016Natur.530..215K. doi:10.1038/nature16510. PMID 26863981. S2CID 205247254.

- ^ a b c d e f Kunimatsu, Y.; Nakatsukasa, M.; Sawada, Y.; Sakai, T. (2007). "A new Late Miocene great ape from Kenya and its implications for the origins of African great apes and humans". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (49): 19220–19225. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10419220K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0706190104. PMC 2148271. PMID 18024593.

- ^ Yasui, Kinya; Nakano, Yoshihiko; Ishida, Hidemi (March 1987). "Excavation at the Fossil-Hominoid-Bearing Locality, Site-SH22 in the Samburu Hills, Northern Kenya". African Study Monographs. Supplementary Issue. 5: 169–174. doi:10.14989/68329. ISSN 0286-9667.

- ^ Morita, W.; Morimoto, N.; Kunimatsu, Y.; et al. (2017). "A morphometric mapping analysis of lower fourth deciduous premolar in hominoids: Implications for phylogenetic relationship between Nakalipithecus and Ouranopithecus". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 116 (5–6): 655–669. Bibcode:2017CRPal..16..655M. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2016.10.004. hdl:2115/71435.

- ^ a b Kunimatsu, Y.; Sawada, Y.; Sakai, T.; et al. (2017). "The latest occurrence of the nyanzapithecines from the early Late Miocene Nakali Formation in Kenya, East Africa". Anthropological Science. 125 (2): 45–51. doi:10.1537/ase.170126.

- ^ Handa, N.; Nakatsukasa., M.; Kunimatsu, Y.; Nakaya, H. (2019). "Additional specimens of Diceros (Perissodactyla, Rhinocerotidae) from the Upper Miocene Nakali Formation in Nakali, central Kenya". Historical Biology. 31 (2): 262–273. doi:10.1080/08912963.2017.1362560. S2CID 135074081.

- ^ a b Benefit, B. R.; Pickford, M. (1986). "Miocene fossil cercopithecoids from Kenya". Physical Journal of Anthropology. 69 (4): 441–464. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330690404.

- ^ Nakaya, H.; Uno, K.; Fukuchi, A.; et al. (13 September 2010). Late Miocene paleoenvironment of hominoids—mesowear analysis of fossil ungulate cheek teeth from northern Kenya. International Primatological Society. Vol. 26. doi:10.14907/primate.26.0.147.0. 147.

- ^ Nakatsukasa, M.; Mbua, E.; Sawada, Y.; et al. (2010). "Earliest colobine skeletons from Nakali, Kenya". Physical Journal of Anthropology. 143 (3): 365–382. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21327. PMID 20949609.

- ^ Kunimatsu, Y.; Nakatsukasa, M.; Sawada, Y. (2016). "A second hominoid species in the early Late Miocene fauna of Nakali (Kenya)". Anthropological Science. 124 (2): 75–83. doi:10.1537/ase.160331.

External links

edit- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).

- "Mama, Is That You? Possible Ape Ancestor Found". Discovery News. Version of 2007-NOV-12. Retrieved 2007-NOV-13. Contains photo of fossil.