Navnirman Andolan (lit. 'the movement for constructive reforms')[1] was a socio-political movement in 1974 in Gujarat by students and middle-class people against economic crisis and corruption in public life. The movement focused on different issues during its duration. It had broadly three goals: the resignation of the Chief Minister; the dissolution of the Gujarat Legislative Assembly; and the social reconstruction.[1] It was one of the successful agitations in the history of post-independence India that resulted in the dissolution of an elected government of the state.[2][3][4]

| Nav Nirman Movement | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Date | 20 December 1973 - 16 March 1974 | |||

| Location | Gujarat, India | |||

| Caused by | Economic crisis and corruption in public life | |||

| Goals | Resignation of Chief Minister, dissolution of state legislative assembly, social reconstruction | |||

| Methods | Protest march, street protest, riot, hunger strike, strike | |||

| Resulted in | Legislative assembly dissolved and fresh elections | |||

| Parties | ||||

| ||||

| Lead figures | ||||

| Violence and action | ||||

| Death(s) | 108[1] | |||

| Injuries | 310[1] | |||

| Arrested | 8237[1] | |||

Background

editIn 1972 Gujarat Legislative Assembly election, the Congress (R) had secured 140 out of 167 seats in the assembly. The internal politics of the party resulted in Chimanbhai Patel becoming the Chief Minister of Gujarat in July 1973 replacing Ghanshyam Oza. There were allegations of corruption against him.[2][1] The urban middle class was facing economic crisis due to the high price of food.[2][3][4]

Movement

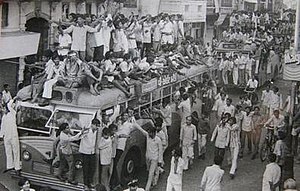

editIn mid-December 1973, at Morbi Engineering College, the students protested against the rise in food fees in mess and damaged furnitures of the department of mechanical engineering and the laboratory. Total 40 students were suspended and the college was closed indefinitely.[1] On 20 December 1973, the students of L. D. College of Engineering in Ahmedabad went on strike in protest against a 20% hike in hostel food fees.[5][6][1] The price rise was related to the withdrawal of the subsidized foodgrains. The same type of strike also organised on 3 January 1974 at Gujarat University resulted in clashes between the police and the students. On students, several rounds of teargas shells were launched and they were lathicharged. On that night, total 326 students were arrested. The students demanded the release and treatment of the arrested students and reinstitution of the subsidized foodgrains. The protesting students formed the committee and met the Chief Minister regarding their demands of the reduction in food fees and the police brutality. As the demands were not fulfilled, the students called for three-day bandh (general strike) of schools and colleges.[1][4] An indefinite strike started on 7 January 1974 in the educational institutions. Their demands were related to food and education.[4]

On 10 January 1974, 14th August Shramjivi Samiti, a committee formed from the 62 employee unions of private sectors and government offices, organised general strike against the inflation and corruption.[1] The strike became violent in Ahmedabad and Vadodara for two days.[4] Middle-class people and some factory workers also joined the protests in Ahmedabad; they also attacked some ration shops.[2] The protests were supported by several organisations such as Gujarat University Area Teachers' Association.[1] By mid-January 1974, students, lawyers and professors organised and formed a lead committee, later known as the Nav Nirman Yuvak Samiti, to voice their grievances and guide the protests.[2][4][1] Similar independent Nav Nirman Samitis were formed in several parts of Gujarat.[1] A statewide strike was organised on 25 January 1974 and resulted in clashes between the police and the people in at least 33 towns.[2] The government imposed a curfew in 44 towns and the agitation spread across Gujarat.[4] The army was called in to restore the peace in Ahmedabad on 28 January 1974.[2][7] The political parties Congress (O), Swatantra Party and Jansangh had also organised their protest programmes.[1]

Several union leaders and student leaders were arrested under the Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA) so several leaders hid themselves. On 29 January 1974, the Police Commissioner Office issued warrants against them which was challenged in the Gujarat High Court three days later. The High Court gave interim relief to the leaders and asked the Police Commissioner to not arrest until the next hearing.[1]

The protesters demanded Chimanbhai Patel's resignation.[4] The protests were continued for 63 days in 23 towns and cities of the state.[1] Due to the pressure of the protests, Indira Gandhi, then the Prime Minister of India, asked Chimanbhai Patel to resign. He resigned on 9 February 1974.[3][4][8] Consequently, the students sought the resignation of the members of the legislative assembly (MLAs) of ruling party as they believed that they are also responsible for the corruption. They started visiting MLAs in their respective constituencies and started forcing them to resign.[1] Opposition parties demanded the dissolution of the assembly.[2]

On 15 February 1974, 15 MLAs of Congress (O) and four MLAs of Congress (R) resigned. Three Jan Sangh MLAs also resigned.[2][1] More and more MLAs resigned as the time progressed. Despite reports from three observers from the national headquarters of the Congress (R), the state Congress (R) was reluctant to dissolve the assembly. Total 214 students went to New Delhi to dialogue with senior Congress (R) leaders but were arrested and jailed for a week for organising protest against the parliament. On 5 March 1974, more than 500 students carried out the sildent rally which travelled 30 km in Delhi.[1]

Following writ petition on 24 February 1974 in the High Court against the Speaker of the assembly for not accepting the resignation of the MLAs, the Speaker accepted the resignation of 18 MLAs the next day.[1] By March, the students had forced 95 of 167 MLAs to resign. Morarji Desai, leader of Congress (O), went on an indefinite fast on 12 March 1974 in support of the demand. On 16 March 1974, the assembly was dissolved and the governor imposed the president's rule, bringing an end to the agitation.[2][3][4][8]

Protest methods and metrics

editOut of 137 protest programmes, 110 were non-violent and the rest were violent. During the protests, the leaders had appealed for non-violent protest. The protest methods included bandhs, satyagrahas, dharanas, rallies, processions and self-imposed curfews. Some unique methods of protest employed included the state transport bus hijackings, the welcome of the Army, burning effigies and conducting last rites of the politicians, organising mock legislative assembly, mock elections, death bell ringing at night, sending protest postcards, sending letters written with blood to the politicians, mock court hearings against politicians, mock cricket match between protestors and politicians.[1] The violent protest methods included arson and vandalism of public and private properties, looting and stone-pelting.[1]

The state government deployed the local police, the state reserve police, the paramilitary forces and the army to maintain the situation. They employed arrests, prohibitory orders, curfews, use of teargas shells, baton charge and firing.[1]

The movement lasted 73 days. Total 103 people died according to official figures which included 88 deaths from police firing. Of these 88, total 61 were below age of 30. Total 310 people were injured according to official figures.[1] According to other figures, between 1,000 to 3,000 people were injured.[2][3] Total 8,053 people were arrested under various laws and 184 were arrested under MISA.[1] The police had fired 1405 rounds of bullets, used 4342 teargas shells and 1654 instances of baton charges.[1]

Aftermath

editThe Nav Nirman Yuvak Samiti demanded the fresh elections and opposition parties supported this. Morarji Desai, leader of Congress (O), again went on an indefinite fast on 6 April 1975 to support it.[2] The fresh elections were held on 10 June 1975 and the result was declared on 12 June 1975.[2] Meanwhile, Chimanbhai Patel formed a new party named Kisan Mazdoor Lok Paksh and contested on his own. Congress (R), which won only 75 seats, lost the elections. Janata Morcha; the coalition of Congress (O), Jan Sangh, Praja Socialist Party (PSP) and Lok Dal; won 88 seats and Babubhai J. Patel became the new chief minister. This government lasted only nine months and the president's rule was imposed in March 1976.[3] Congress won the elections in December 1976 and Madhav Singh Solanki became the new Chief Minister.[2][3]

Impact and legacy

editJayaprakash Narayan visited Gujarat on 11 February 1974, after Chimanbhai Patel's resignation, though he was not involved in the movement. The Bihar Movement had already begun in Bihar. It inspired him to lead it and turn it into a total revolution movement, which resulted in the Emergency.[2][4] On 12 June 1975, the court verdict on Indira Gandhi's electoral malpractice was declared which disqualify her from the parliament and thus she imposed the Emergency.[2] Later Janata Morcha became precursor of the Janata Party, which formed the first non-Congress government winning the general election against Indira Gandhi in 1977, and Morarji Desai became prime minister.[3][9][10]

Congress formed a new caste-based election combination known as KHAM (Kshtriya-Harijan-Adivasi-Muslim) in late 1970s to elevate itself in politics. The upper caste sensed it as the end of their political importance and reacted strongly against the imposition of reservations in 1981.[5] This ultimately provoked the anti-Mandal riots in 1985, which helped the rise of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in Gujarat.[11]

Chimanbhai Patel became chief minister again with the BJP support in 1990.[2]

The agitation helped local leaders of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and its student organization ABVP to establish themselves in politics. Narendra Modi who later served as the Chief Minister of Gujarat from 2001 to 2014, and was subsequently elected as the Prime Minister of India in 2014, was one of them.[2]

The Navnirman movement reflected the anger of middle-class people and students at the prevalent economic crisis and corruption in government. It also showed the people's power to change the government by forcing it to resign by protesting.[2][8] The movement raised the political awareness among the youth and promoted students' leadership.[1]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Bhagat-Ganguly, Varsha (2014). "Revisiting the Nav Nirman Andolan of Gujarat". Sociological Bulletin. 63 (1): 95–112. ISSN 0038-0229.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Ananth, V. Krishna (2011). India Since Independence: Making Sense of Indian Politics. Pearson Education India. p. 117. ISBN 978-81-317-3465-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Dhar, P. N. (2000). Excerpted from 'Indira Gandhi, the "emergency", and Indian democracy' published in Business Standard. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195648997. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Shah, Ghanshyam (20 December 2007). "Pulse of the people". India Today. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ a b jain, Arun Kumar (1978). Political Science. FK Publication. p. 114. ISBN 9788189611866.

- ^ "नवनिर्माणांच्या शिल्पकार" [Architect of Navnirman Movement]. Loksatta (in Marathi). 11 June 2016. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "1974: India inspired by Gujarat uprising". The Times of India. 18 February 2017. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ a b c Bhagat-Ganguly, Varsha (2014). "Revisiting the Nav Nirman Andolan of Gujarat". Sociological Bulletin. 63 (1): 95–112. doi:10.1177/0038022920140106. S2CID 185751051.

- ^ Katherine Frank (2002). Indira: The Life of Indira Nehru Gandhi. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 371. ISBN 978-0-395-73097-3.

- ^ "The Rise of Indira Gandhi". Library of Congress Country Studies. Retrieved 27 June 2009.

- ^ Sanghavi, Nagindas (15 October 2010). Mehta, Nalin; Mehta, Mona G. (eds.). "From Navnirman to the anti-Mandal riots: the political trajectory of Gujarat (1974–1985)" [Gujarat Beyond Gandhi: Identity, Conflict and Society]. South Asian History and Culture. Issue 4. 1 (4): 480–493. doi:10.1080/19472498.2010.507021. S2CID 144157465.

Further reading

edit- Krishna, Ananth V. (1 September 2011). India Since Independence: Making Sense of Indian Politics. Pearson Education India. p. 117. ISBN 9788131734650.

- Sheth, Pravin N. (1977). Nav Nirman & political change in India: from Gujarat 1974 to New Delhi 1977. Vora.