Niaprazine (INN) (brand name Nopron) is a sedative-hypnotic drug of the phenylpiperazine group.[1][2] It has been used in the treatment of sleep disturbances since the early 1970s in several European countries including France, Italy, and Luxembourg.[3][4] It is commonly used with children and adolescents on account of its favorable safety and tolerability profile and lack of abuse potential.[5][6][7][8][9][10]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Nopron |

| Other names | CERM-1709 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Elimination half-life | ~4.5 hours |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.044.014 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

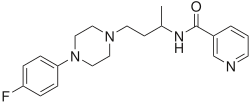

| Formula | C20H25FN4O |

| Molar mass | 356.445 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Originally believed to act as an antihistamine and anticholinergic,[11] niaprazine was later discovered to have low or no binding affinity for the H1 and mACh receptors (Ki = > 1 μM), and was instead found to act as a potent and selective 5-HT2A and α1-adrenergic receptor antagonist (Ki = 75 nM and 86 nM, respectively).[12] It possesses low or no affinity for the 5-HT1A, 5-HT2B, D2, and β-adrenergic, as well as at SERT and VMAT (Ki = all > 1 μM), but it does have some affinity for the α2-adrenergic receptor (Ki = 730 nM).[12]

Niaprazine has been shown to metabolize to the compound para-fluorophenylpiperazine (pFPP) in a similar manner to how trazodone and nefazodone metabolize to meta-chlorophenylpiperazine (mCPP).[13][14] It is unclear what role, if any, pFPP plays in the clinical effects of niaprazine.[12] However, from animal studies it is known that pFPP, unlike niaprazine, does not produce sedative effects, and instead exerts a behavioral profile indicative of serotonergic activation.[13]

Synthesis

editA Mannich reaction using 4-fluorophenylpiperazine (1), 1,3,5-trioxane (2) and acetone gives the ketone (4). Reaction with hydroxylamine produces the oxime, (5), which is reduced with lithium aluminium hydride to give the amine (6). Amide formation with nicotinic acid (7), activated as its acid chloride, yields nilaprazine.[15][16]

References

edit- ^ Elks J (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 862–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- ^ Kent A, Billiard M (2003). Sleep: physiology, investigations, and medicine. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum. ISBN 978-0-306-47406-4.

- ^ Swiss Pharmaceutical Society (2000). Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory (Book with CD-ROM). Boca Raton: Medpharm Scientific Publishers. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- ^ Triggle DJ (1996). Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC. ISBN 978-0-412-46630-4.

- ^ Franzoni E, Masoni P, Mambelli M, Marzano P, Donati C (1987). "[Niaprazine in behavior disorders in children. Double-blind comparison with placebo]". La Pediatria Medica e Chirurgica: Medical and Surgical Pediatrics (in Italian). 9 (2): 185–7. PMID 2958783.

- ^ Bodiou C, Bavoux F (1988). "[Niaprazine and side effects in pediatrics. Cooperative evaluation of French centers of pharmacovigilance]". Thérapie (in French). 43 (4): 307–11. PMID 2903572.

- ^ Ottaviano S, Giannotti F, Cortesi F (October 1991). "The effect of niaprazine on some common sleep disorders in children. A double-blind clinical trial by means of continuous home-videorecorded sleep". Child's Nervous System. 7 (6): 332–5. doi:10.1007/bf00304832. PMID 1837245. S2CID 35908448.

- ^ Montanari G, Schiaulini P, Covre A, Steffan A, Furlanut M (1992). "Niaprazine vs chlordesmethyldiazepam in sleep disturbances in pediatric outpatients". Pharmacological Research. 25 (Suppl 1): 83–4. doi:10.1016/1043-6618(92)90551-l. PMID 1354861.

- ^ Younus M, Labellarte MJ (2002). "Insomnia in children: when are hypnotics indicated?". Paediatric Drugs. 4 (6): 391–403. doi:10.2165/00128072-200204060-00006. PMID 12038875. S2CID 33340367.

- ^ Mancini J, Thirion X, Masut A, et al. (July 2006). "Anxiolytics, hypnotics, and antidepressants dispensed to adolescents in a French region in 2002". Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 15 (7): 494–503. doi:10.1002/pds.1258. PMID 16700077. S2CID 24273650.

- ^ Duchene-Marullaz P, Rispat G, Perriere JP, Hache J, Labrid C (1971). "[Some pharmacodynamical properties of niaprazine, a new antihistaminic agent]". Thérapie (in French). 26 (6): 1203–9. PMID 4401719.

- ^ a b c Scherman D, Hamon M, Gozlan H, et al. (1988). "Molecular pharmacology of niaprazine". Progress in Neuro-psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 12 (6): 989–1001. doi:10.1016/0278-5846(88)90093-0. PMID 2853885. S2CID 40566589.

- ^ a b Keane PE, Strolin Benedetti M, Dow J (February 1982). "The effect of niaprazine on the turnover of 5-hydroxytryptamine in the rat brain". Neuropharmacology. 21 (2): 163–9. doi:10.1016/0028-3908(82)90157-5. PMID 6460945. S2CID 22310059.

- ^ Garattini S, Mennini T (1988). "Critical notes on the specificity of drugs in the study of metabolism and functions of brain monoamines". International Review of Neurobiology. 29: 259–80. doi:10.1016/s0074-7742(08)60089-6. ISBN 9780123668295. PMID 3042665.

- ^ US patent 3712893, J Simond, J Moleyre, R Mauvernay, N Busch, "Butyl-piperazine derivatives", issued 1973-01-23, assigned to Centre Europeen de Recherches Mauvernay

- ^ "Niaprazine". Pharmaceutical Substances. Thieme. Retrieved 2024-07-17.