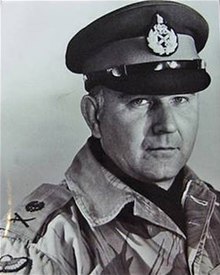

Lieutenant General George Peter Walls GLM DCD MBE (1927[1] – 20 July 2010) was a Rhodesian soldier. He served as the Head of the Armed Forces of Rhodesia during the Rhodesian Bush War from 1977 until his exile from the country in 1980.[2][3]

George Peter Walls | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s) | Peter |

| Born | 1927 Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia (now Harare, Zimbabwe) |

| Died | 20 July 2010 (aged 82–83) George, Western Cape, South Africa |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1946–1980 |

| Rank | Lieutenant General |

| Unit | |

| Commands | |

| Battles / wars | |

| Awards | |

| Spouse(s) | Eunice (wife) |

| Relations | Three daughters and a son |

Early life

editGeorge Peter Walls was born in Salisbury, the capital of the British self-governing colony of Southern Rhodesia, in 1927. His mother was Philomena and father was George Walls, a pilot, who had seen service with the Royal Air Force (RAF) in the First World War. He received his initial education at Plumtree School in Southern Rhodesia.

Early military career

editIn the closing months of the Second World War, he left Southern Rhodesia for England, where he received his initial military education at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst.[1] He was commissioned on 16 March 1946 into the Black Watch regiment of the British Army.[4]

Return to Africa

editResigning his commission in the British Army, apparently dissatisfied with a proposal to transfer him to another regiment from the Black Watch, he returned home and re-enlisted with the Rhodesian Army, first as a non-commissioned officer in the Southern Rhodesian Staff Corps, and then as an officer in the Northern Rhodesia Regiment.[5]

Malayan Emergency

editIn 1951, Walls was promoted to the rank of Captain at the age of 24 years, and was appointed second-in-command of a reconnaissance unit that Rhodesia despatched to fight in the Malayan Emergency. On arrival in Malaya this unit was renamed "C" Squadron, Special Air Service, and Walls, proving his fighting and leadership qualities in the Malayan jungle, was promoted to the rank of Major, and appointed as the unit's Commanding Officer. On the conclusion of the victorious campaign after 2 years, Walls was appointed an M.B.E. (Military) in 1953.[6]

Southern Rhodesia

editReturning home to Southern Rhodesia, Walls continued as a career soldier, holding a succession of General Staff posts in the Rhodesian Army, and attending the British Army's Staff College in England for training as a future senior officer. In November 1964, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel and appointed to be the Commanding Officer of the 1st Battalion of the Rhodesian Light Infantry.

With the advent of global decolonisation, Southern Rhodesia came under increasing political pressure from the Colonial Office and the United Nations to introduce universal suffrage and majority rule. In response, Ian Smith, then Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia, and his Cabinet issued a unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) from the United Kingdom in November 1965, claiming that Southern Rhodesia was now independent as a dominion within the Commonwealth called Rhodesia. During this period, Brigadier Sam Putterill, Walls' commanding officer, reproached him for permitting his men to wear paper party hats at a regimental Christmas dinner printed with the words, "RLI for UDI." Rhodesia declared itself a republic in 1970.

General Staff Officer

editAfter UDI, in the new Rhodesia, Walls was promoted to Brigadier, and appointed to the command of the Rhodesian Army's 2nd Brigade. In the late 1960s he was appointed to the post of the Rhodesian Army's Chief of Staff, with the rank of Major-General. In 1972 he was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant General and appointed to the post of the Commander-in-Chief of the Rhodesian Army.[7] In 1977 he was appointed as the head of Rhodesian Joint Operations Command, becoming de facto with this office the Head of the Rhodesian Armed Forces.[3][8]

Rhodesian Bush War

editAs international pressure upon the Rhodesian government to admit more indigenous Africans into the country's governance increased during the late 1960s, exerted by crippling economic sanctions, guerrilla activity intensified among the Shona and the Ndebele with support from the Chinese and Soviet governments, as a part of their Cold War strategy against Western presence in Africa. This support brought in modern weapons and training for the tribal forces, and the guerrilla activity escalated through the 1970s into full-scale guerrilla warfare (known as the Rhodesian Bush War) in the Rhodesian countryside between the guerillas and the Rhodesian authorities – with Walls as the leader of the armed forces directing operations in the increasingly besieged nation. Many of these operations involved incursion raids into the neighbouring territories of Zambia, Mozambique, Tanzania, Botswana and Angola, which were covertly harbouring the guerrillas of the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA) and the Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA).

In 1973, after a study as to the nature of the opponents that Rhodesia was facing, Walls summoned Ronald Reid-Daly and asked him to assemble a new army unit in response to the strategic nature of the escalating guerilla tactics of Rhodesia's adversaries. The new unit needed to combine cross-border insurgency warfare to take the fight to the enemies' bases of operation in territory under hostile governmental control (which collectively virtually encircled Rhodesia), with domestic policing counter-insurgency operations of a more traditional colonial nature, both disciplines being drawn heavily from the experiences that both Walls and Reid-Daly had learned when they had fought alongside one another in the Malayan Emergency twenty years earlier. The new unit was the Selous Scouts.[9]

In 1976, Walls oversaw the introduction of indigenous Africans into the Rhodesian Army as commissioned officers for the first time.[10]

In 1977, Walls was appointed as Rhodesia's Commander, Combined Operations, commanding the nation's military and police forces, providing him with almost 50,000 men under his orders in increasingly severe fighting. On 3 April 1977, in a sign that time was running out for Rhodesia amid economic sanctions, Walls announced that the government would launch a campaign to win the "hearts and minds" of Rhodesia's indigenous African populations to undermine support for the guerrilla campaigns.[11]

In May 1977, General Walls received intelligence reports of a ZANLA force massing in the town of Mapai, in the neighbouring country of Mozambique, and he launched an attack across the border to remove the threat. At this time Walls briefed the press that the Rhodesian forces were changing tactics from "contain and hold" to "search and destroy", and adopting a military policy of "hot pursuit when necessary." On 30 May 1977, a force of around five hundred Rhodesian troops crossed the border into Mozambique (which had only gained independence from Portugal in 1975), engaging the enemy with support from the Rhodesian Air Force (RhAF), and paratroopers conveyed in Second World War-era C-47 Dakotas. At the end of the operation, General Walls announced that it had killed 32 guerrillas for the loss of one Rhodesian pilot in action. Mozambique's government disputed the number of casualties, stating it had shot down four Rhodesian aircraft and taken several Rhodesian prisoners of war, which the Rhodesian government denied.[12][13][14] Walls announced a day later that the Rhodesian Army would occupy the captured area of Mozambique until it had removed nationalist guerrillas from it. Kurt Waldheim, the Secretary-General of the United Nations, condemned the incident on 1 June, and political pressure, led by the United States, prompted the Rhodesian government to order its forces out of Mozambique.[12]

In November 1977, Walls commanded another raid into Mozambique entitled Operation Dingo, inflicting heavy losses on ZANLA guerrillas quartered there. In a candid admission to the press, Walls gave an insight to the nature of the conflict that Rhodesia found itself in when he stated in an interview in September 1978 that: "There is no single day of the year when we are not operating beyond our borders."[15]

In 1977, rumours began circulating in the Rhodesian press that Walls had become deeply pessimistic about the future of Rhodesia, and that he had been quietly preparing to abandon the country and personally relocate his family into South Africa, and had covertly purchased property there for this purpose. Seeking to scotch these allegations, with the attenuation they would have to the military morale of the troops still fighting under his command, he publicly issued a denial they had any basis in truth.[16]

On 4 September 1978 a combined NATJOC meeting was held which Ian Smith attended. This was the day after the first Viscount tragedy. It appears that in the meeting after Smith had left the meeting, the Generals or elements of NATJOC rebelled and decided to approach the British Government to find out if a coup was staged, what would be the British Government's position, if Rhodesia was returned to British rule. Declassified minutes of the British Cabinet meeting of 7 September 1978 shows that the British were approached (cab-128-64 of the British archives). Any approach by these senior Generals would hand the British a significant advantage in future negotiations. This also compromised Ian Smith's hand at the Lancaster House Conference.

On 4 November 1978, Walls announced to the press that 2,000 nationalist guerrillas had been persuaded to lay down their arms (this figure has been placed by subsequent historical research at closer to no more than 50).[11]

On 12 February 1979, in an attempt to assassinate Walls, ZIPRA shot down Air Rhodesia Flight 827 with a Soviet-made SAM-7 missile. Flight 827 was a regularly scheduled flight from Kariba to Salisbury. The aircraft was a Vickers Viscount known as The Umniati, and the second civilian Viscount they had shot down. All 55 passengers and 4 crew on board were killed. But Walls and his wife had missed the flight and were aboard a second Viscount which took off 15 minutes later, and which landed unharmed at Salisbury. The Zimbabwe African People's Union leader Joshua Nkomo appeared on British domestic television laughing about this incident, declaring that Walls was responsible for the passengers' deaths because he was the "biggest military target", and this justified the action.[17] The Rhodesian government responded to the attack by air-strikes on ZIPRA bases within the borders of Angola and Zambia.[18]

With the nation increasingly pressured by sanctions, the Rhodesian government offered an amnesty to the nationalist guerrillas operating in the field in March 1979, printing and distributing 1.5 million leaflets entitled: "TO ALL ZIPRA FORCES". The leaflets were printed with the signatures of Prime Minister Ian Smith, the ZANU founder Ndabaningi Sithole, United African National Council leader Abel Muzorewa, Chief Jeremiah Chirau, and Walls. Any who abandoned the Bush War were offered suffrage, food and medical treatment. Following this in April 1979, Walls issued an order to the Selous Scouts Regiment to train, organise, and support militants who had defected to the Rhodesian government's authority as part of Operation Favour.[11] However this hearts and minds approach had only limited success, and the Bush War continued unabated. Following the Internal Settlement, Zimbabwe Rhodesia's government concluded a ceasefire with the Patriotic Front ahead of negotiations in London.

Zimbabwe

editIn late 1979, at a peace conference held in at Lancaster House in London, the UK, the Government of Zimbabwe Rhodesia, and the Patriotic Front guerrilla leaders, concluded the Lancaster House Agreement, leading to elections in March 1980 with universal suffrage extended to all the country's citizens. The election was won by ZANU-PF and its leader Robert Mugabe, who became Prime Minister of the newly declared nation of Zimbabwe on its formal independence in April 1980.

Amid the international community's welcome of these developments, Lieutenant-General Walls publicly announced to the press his support for the new government and national dispensation of the Zimbabwean state.[19] This caused some surprise in military, political and diplomatic circles involved, and acrimony between himself and Rhodesia's last Prime Minister, Ian Smith (who had known Walls' father when they had served together in the Royal Air Force),[20] who privately accused him of betrayal[21] during the negotiations in London for the Lancaster House Agreement.[22] In consequence of his newly found conciliatory demeanour, Walls was maintained as the Commanding Officer of the new Zimbabwe national army by the new Government to oversee the integration of the black nationalist guerrilla units into its regular armed forces.

Whilst the Western press and governments praised Mugabe's early announcements of his aim of reconciliation with the white community, tensions swiftly developed on the ground.[1] On 17 March 1980, only a few days after the election of the new government, a rumour of a coup attempt led Mugabe to confront Walls with the question: "Why are your men trying to kill me?" Walls replied: "If they were my men you would be dead."[23]

Whites continued to leave the country for South Africa, and relations between the two men continued to deteriorate. In an interview with the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) in August 1980, Walls stated that he had requested British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher annul the March 1980 election results prior to the official announcement of the result. His request was based on the grounds that Robert Mugabe's forces had used intimidation of voters at the hustings and polling stations to win. Walls stated that there had also been multiple breaches of military aspects of the Lancaster House Agreement's terms.[24] He noted that the British Government had not even replied to his request.

On 12 August 1980, the British Government issued a statement in response to the interview stating that Antony Duff, at that time the Deputy Governor of Salisbury, had replied to Walls in March 1980, notifying him that it would not interfere with the election.[2] Walls also later revealed that he had raised the same concerns during the election and transfer of power in March 1980 with the British Government's Foreign and Commonwealth Office officials who were overseeing the election, led by Lord Soames as the last Governor of Southern Rhodesia (who were more concerned that the Rhodesian military were about to stage a coup d'état to prevent the handover of power to the native African electorate), but had been told that they were not willing to annul the election process as Mugabe had, in their assessment, the overwhelming support of the native African population anyway, and the US government would be against it.[25]

In response to the release of the interview with the BBC, the Zimbabwean Minister of Information, Nathan Shamuyarira, issued a statement that the new Government: "Would not be held ransom by racial misfits", and suggested that "all those Europeans who do not accept the new order should pack their bags." He also stated that the Zimbabwean government was now considering legal or administrative action against Lt. Gen. Walls for his comments in the BBC interview. On returning from a meeting in the US with President Jimmy Carter, Prime Minister Mugabe, on hearing of the interview, said: "We are certainly not going to have disloyal characters in our society."

Walls returned to Zimbabwe after the interview, telling Peter Hawthorne of Time magazine: "To stay away at this time would have appeared like an admission of guilt." Subsequently, the government removed him from his military post at the head of its armed forces and passed an order essentially precluding his presence within Zimbabwe's territory. Walls left the country at the end of 1980 to live in exile in South Africa.[26][27]

Military awards

editWhilst a temporary major in the Southern Rhodesia Far East Volunteer Unit (Staff Corps) he was awarded the M.B.E. in recognition of his service in Malaya.[28]

Walls was the only recipient of the Grand Officer (Military Division) of the Rhodesian Legion of Merit. He was entitled to the post-nominal letters G.L.M. His ribbons are as follows.[29]

| Ribbon | Description | Notes |

| Zimbabwean Independence Medal | ||

| Grand Officer of the Legion of Merit |

| |

| Defence Cross for Distinguished Service | ||

| General Service Medal | ||

| Exemplary Service Medal | ||

| Member of the Order of the British Empire |

| |

| War Medal 1939–1945 | ||

| General Service Medal (1918) |

| |

| Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal |

|

Final years

editWalls settled with his wife at Plettenberg Bay in the Western Cape of South Africa, where he spent the remainder of his life in obscurity away from the public eye.

At the turn of the century, as Zimbabwe became an economically chaotic state, the Government began to seize the properties and farmsteads of the remaining white farming population in an atmosphere of escalating menace and violence. Paranoia also increased in the Government about perceived potential threats from the previous era to its rule becoming a focus for popular discontent; this was publicly displayed by articles appearing in state controlled press outlets[30] circulating rumours that Walls had covertly been crossing the border into Zimbabwe from South Africa to support the Movement for Democratic Change. Obert Mpofu, ZANU-PF Party Deputy Secretary for Security stated publicly that Walls had been seen in the vicinity of the Victoria Falls. Walls subsequently denied these reports in response to press enquiries, with: "It's utter bloody rubbish, I haven't been out of the Western Cape this year, except to go to Johannesburg once. I haven't been in Zimbabwe since I left in 1980. I have no connection with any group whatsoever in Zimbabwe."[26] The Daily News later reported the Zimbabwean Government had confused Walls with Peter Wells, an English agronomist who had visited Harare to assist African farmers with water management.

During the night of 23 February 2001, a gang of black Zimbabweans attacked Walls' son, George, in Harare. Identifying themselves as Bush War veterans, they waylaid his car, demanded to know his father's whereabouts, and then proceeded to assault him, cutting his face and stabbing him in the thigh.[31]

Death

editGeneral Walls died in his 83rd year on 20 July 2010 at George Airport (formerly P.W. Botha Airport) on the outskirts of George in the Western Cape, South Africa, whilst traveling with his wife for a holiday at the Kruger National Park.

His funeral was conducted on 27 July 2010 at St. Thomas' (Anglican) Church, Randburg, Gauteng, South Africa.

Personal life

editWalls was survived by his wife, Eunice, and four children from his first marriage: three daughters named Patricia, Marion, and Valerie, and one son named George.[32][33]

References

edit- ^ a b c -2010 Walls: "We will make it work" Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine Time magazine and CNN

- ^ a b Kalley, Jacqueline Audrey. Southern African Political History: A chronological of key political events from independence to mid-1997, 1999. Page 711–712.

- ^ a b Peter Abbott and Philip Botham. Modern African Wars (1): Rhodesia 1965–80, 1986. Page 11.

- ^ "No. 37544". The London Gazette (Supplement). 23 April 1946. p. 2038.

- ^ Obituary for Lt. Gen. Peter Walls, 'Daily Telegraph' 27 July 2010.

- ^ Obituary for Lt. Gen. Peter Walls, 'The Guardian' newspaper (England), 28 July 2010.

- ^ Obituary for Lt. Gen. Peter Walls, 'The Guardian', 28 July 2010.

- ^ Wood, J. R. T. 'So Far and No Further!' Rhodesia's Bid for Independence During the Retreat from Empire 1959, 2005, p. 244

- ^ 'Lt. Gen. Peter Walls obituary, 'Daily Telegraph', 27 July 2010.

- ^ AFP Report, 'First black officers graduate into Rhodesian Army', 11 June 1977 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-SqmYYNH6rA

- ^ a b c Rhodesia Psychological Operations 1965–1980 Psychological Operations

- ^ a b Kalley, Jacqueline Audrey. Southern African Political History: A chronological of key political events from independence to mid-1997, 1999. Page 224.

- ^ Smith Takes a Dangerous New Gamble TIME magazine and CNN

- ^ Getting ready for war TIME magazine and CNN

- ^ Preston, Matthew. Ending Civil War: Rhodesia and Lebanon in Perspective, 2004. Page 65.

- ^ AFP Report, 'General Peter Walls presents troops with trophy Gweru', 26 August 1979 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H2qGmbZpwAA

- ^ Again, death on "Flight SAM-7" TIME magazine and CNN

- ^ Sibanda, Eliakim M. The Zimbabwe African People's Union, 1961–87: A Political History of Insurgency in Southern Rhodesia, 2004. Page 196.

- ^ "We will make it work!", interview with Lt. Gen. Peter Walls, 'Time' Magazine, 24 March 1980.

- ^ Lt.Gen Peter Walls obituary, 'Daily Telegraph' 27 July 2010.

- ^ Obituary Lt. Gen. Peter Walls, 'Daily Telegraph', 27 July 2010.

- ^ 'Bitter Harvest, The Great Betrayal', by Ian Smith (Pub. Blake Publishing, 2008).

- ^ Raymond, Walter John. Dictionary of Politics: Selected American and Foreign Political and Legal Terms, 1992. Page 557.

- ^ Interview with Peter Walls, 'End of Empire' Part 14 Granada Television documentary (1985).

- ^ Interview with Peter Walls, 'End of Empire', Episode #14 television documentary, Granada Television (1985).

- ^ a b Zanu-PF's Walls 'manhunt' backfires Archived 30 November 2003 at the Wayback Machine Dispatch

- ^ A soldier faces his critics TIME magazine and CNN

- ^ "No. 39839". The London Gazette (Supplement). 28 April 1953. p. 2405.

- ^ AFP Report, 'General Peter Walls Press Conference', 20 July 1980 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3EK4sVtVEQs

- ^ 'The Herald' (Zimbabwe) 20 December 2000.

- ^ Blair, David (27 February 2001). "Ex-Rhodesian army chief's son attacked". The Daily Telegraph. Harare.

- ^ Cowell, Alan (22 July 2010). "Peter Walls, General in Zimbabwe, Dies at 83". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ "Lieutenant-General Peter Walls". www.telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 7 January 2022.