This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2008) |

Raymond Benjamin Caldwell (April 26, 1888 – August 17, 1967) was an American professional baseball pitcher who played in Major League Baseball for the New York Yankees, Boston Red Sox, and Cleveland Indians from 1910 to 1921. He was known for throwing the spitball, and he was one of the 17 pitchers allowed to continue throwing the pitch after it was outlawed in 1920.[1]

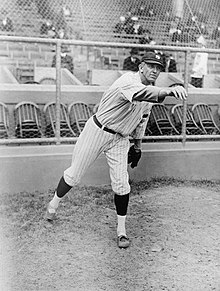

| Ray Caldwell | |

|---|---|

Caldwell with the New York Yankees in 1918 | |

| Pitcher | |

| Born: April 26, 1888 Corydon, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| Died: August 17, 1967 (aged 79) Salamanca, New York, U.S. | |

Batted: Left Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| September 9, 1910, for the New York Yankees | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| September 29, 1921, for the Cleveland Indians | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Win–loss record | 134–120 |

| Earned run average | 3.22 |

| Strikeouts | 1,006 |

| Stats at Baseball Reference | |

| Teams | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

Caldwell was notorious during his playing career for his addiction to alcohol and partying; he possessed a self-destructive streak that many of his contemporaries believed stopped him from reaching his potential.[2] In 1924, Miller Huggins wrote: "Caldwell was one of the best pitchers that ever lived, but he was one of those characters that keep a manager in a constant worry. If he had possessed a sense of responsibility and balance, Ray Caldwell would have gone down in history as one of the greatest of all pitchers."[3]

Early life

editCaldwell was born in the (now mostly abandoned) town of Corydon, Pennsylvania, located just south of the New York state line near Cattaraugus County. He was the son of Anna (née Archer) and Walter Caldwell. The family later moved to Salamanca in the same county where Ray grew up and completed high school.[4]

Playing career

editHe began his professional career with the McKeesport Tubers of the Ohio–Pennsylvania League in 1910 and recorded 18 wins before being signed by the New York Highlanders in September of that year. In his rookie season he went 14–14 with an earned run average of 3.35, he also recorded a batting average of .272 (during the course of the season he played 11 games in the outfield, and also made numerous appearances as a pinch hitter).

Persistent problems with his throwing arm led to a record of 8–16 and an earned run average of 4.47 in 1912. He regained his form the following year, going 9–8 with 2.41 earned run average for a newly renamed Yankees club that finished 37 games below .500. The 1914 season was the greatest of his career, going 17–9 with a 1.94 earned run average for another Yankees team that finished well below .500. During the course of the season he had numerous run-ins with manager Frank Chance, resulting in his being fined on several occasions for drunkenness and general poor conduct. Towards the end of the season, Caldwell asked team owner Frank Farrell to rescind his fines—which by that point accounted for a substantial proportion of his annual wages. Farrell, fearing that Caldwell would follow former teammates Russ Ford and Hal Chase in accepting an offer to pitch for the Buffalo Buffeds of the Federal League, agreed to let Caldwell off. As a consequence of this, Frank Chance, feeling that his authority had been irrevocably undermined, handed in his resignation as manager of the Yankees.

In 1915, Caldwell once again posted a winning record—19–16, with an earned run average of 2.89—for a Yankees team that finished 14 games below .500. He also contributed four home runs during the course of the season, enough to finish ninth in the American League in that category, despite having more than 200 fewer at bats than anyone else inside the top 10.

The Yankees were a winning team in 1916, but Caldwell had major struggles, both on and off the field. His difficulties on the mound were not helped by his continuing to pitch with a broken patella. By the end of July his record was 5–12, and he had recorded an earned run average of 2.99. It was at this point that Caldwell, whose alcoholism had become increasingly pronounced during the course of the season, went AWOL. Bill Donovan, the Yankees manager—who prior to this had always turned a blind eye to Caldwell's personal problems—issued a fine and suspended him for two weeks. However, Caldwell failed to return to the club after this period had elapsed and he was suspended for the rest of the season.

Caldwell did not return to the Yankees until the following March, more than a week into spring training. Caldwell's whereabouts during the intervening seven months, although much speculated on, were never revealed. Donovan and the Yankees owner, Til Huston, both of whom had strongly criticized Caldwell during his absence, decided to give him another chance, largely influenced by his apparent good condition. However, once again, his performances on the field were overshadowed somewhat by his actions off it. He finished the year 13–16 with a 2.86 earned run average for yet another Yankees team that finished well short of .500. During the course of the season he again served a team-imposed suspension for getting drunk and failing to report for duty. He was charged with grand larceny half-way through the season for allegedly stealing a ring, and was also taken to court by his wife, who sued for alimony after he abandoned her and their son.

In 1918, Caldwell once again failed to complete a season with the Yankees. Injuries hampered him on the mound, but he still managed to compile a batting average of .291 during 151 at-bats. Prior to leaving the club, Caldwell went 9–8 with an earned run average of 3.06. Caldwell left the Yankees in mid-August to join a shipbuilding firm in order to avoid military service after being picked in the draft. Joining a shipbuilding company was attractive to Caldwell, as it was for others, because it offered him the chance of playing baseball for the company rather than actually working on the assembly line. Despite this, the Yankees had not given Caldwell permission to leave the club mid-season and it was decided that he should be traded. In the winter of that year Caldwell was traded to the Boston Red Sox in a deal that also saw Duffy Lewis and Ernie Shore go the other way.

Caldwell was released by the Red Sox in July 1919 after a poor start to the season, in which he compiled an earned run average of 3.94 (his record, however, was 7–4). Caldwell finished the season with the Indians, managed by player-manager Tris Speaker. When he met Speaker to sign a contract, he was initially confused by the wording, as it did not tell him to avoid alcohol after pitching games. Speaker told him it was intentional, aiming for Caldwell to stick to a specific regimen: pitch, drink, sleep the hangover the next day, then come back for wind sprints two days later and batting practice the day after that.[5] Caldwell was struck by lightning while playing for the Cleveland Indians against the Philadelphia Athletics in 1919; despite being knocked unconscious, he refused to leave the game, having pitched 8+2⁄3 innings, and went on to record the final out for the win.[4][2] For the six starts Caldwell made that year with Cleveland, he went 5–1 with a 1.71 earned run average. This included the game where he was struck by lightning and a no-hitter against his former longtime teammates, the New York Yankees, on September 10.

In his first full season with the Indians, in 1920, Caldwell went 20–10, with a 3.86 earned run average. The Indians went on to win the World Series that year, although Caldwell's contribution to that success proved to be negligible. He started Game 3, but recorded just one out, having given up two hits, a walk, and an earned run, before being lifted by Tris Speaker (the Indians did not come back from this, and Caldwell was charged with the loss).

Caldwell's final season in the majors was in 1921, during which he primarily worked from the bullpen. His record was 6–6, with an earned run average of 4.90. After leaving the Indians, Caldwell went on to spend many years playing for various clubs in the minor leagues, including the Kansas City Blues and the Birmingham Barons. At the age of 43, Caldwell faced 21-year-old Houston Buffaloes star Dizzy Dean in the opening game of the 1931 Dixie Series, which Dean had promised to win. Writer Zipp Newman later dubbed the matchup "the strength of youth versus the guile of the years". Caldwell pitched a shutout and also knocked in the only run to give the Barons a 1–0 victory on the way to winning the series.[6]

Caldwell's long-established reputation dissuaded any major league outfit from giving him another chance.

Caldwell was a very good hitting pitcher in his career, posting a .248 batting average (289-for-1164) with 138 runs, eight home runs, 114 RBIs and 78 base on balls. He had 10 or more RBI in a season six times, with a career high 20 RBI with the 1915 New York Yankees. He also played at all three outfield positions and first base in the majors.

Later life

editCaldwell bought a farm in Frewsburg in 1940 and worked at the train station at Ashville as a telegrapher for the Buffalo, Rochester and Pittsburgh Railway. He later worked as a steward and bartender at the Lakewood Rod & Gun Club, where his fourth wife, Estelle, was a cook.[4]

Caldwell died in Salamanca, New York, on August 17, 1967, and is buried in Randolph. He was inducted into the Chautauqua Sports Hall of Fame in 2010.[4]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ "Ray Caldwell - BaseballBiography.com". baseballbiography.com. August 22, 2022. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ a b Brady, Erik (April 20, 2022). "Remembering Salamanca's own 'Remarkable Ray Caldwell,' who brought the heat and survived the lightning". The Buffalo News. Archived from the original on April 20, 2022. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- ^ Miller Huggins. San Francisco Chronicle, March 14, 1924.

- ^ a b c d "Ray Caldwell – Chautauqua Sports Hall of Fame". www.chautauquasportshalloffame.org. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ "The incredible story of the MLB pitcher who survived a lightning strike to finish a game". ESPN.com. August 24, 2021. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ "Ray Caldwell". SABR.org. n.d. Retrieved July 13, 2024.

References

edit- Spatz, Lyle (2000). Yankees Coming, Yankees Going: New York Yankee Player Transactions, 1903 Through 1999. Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland, ISBN 0-7864-0787-5.

External links

edit- Career statistics from Baseball Reference, or Baseball Reference (Minors)