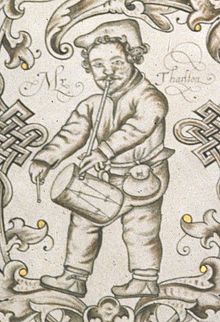

Richard Tarlton (died 5 September 1588) was an English actor of the Elizabethan era. He was the most famous clown of his era, known for his extempore comic doggerel verse, which came to be known as "Tarltons". He helped to turn Elizabethan theatre into a form of mass entertainment paving the way for the Shakespearean stage. After his death many witticisms and pranks were attributed to him and were published as Tarlton's Jests.

Tarlton was also an accomplished dancer, musician and fencer. He was also a writer, authoring a number of jigs, pamphlets and at least one full-length play.

Early life

editInformation on Tarlton's family background is meagre. His father's first name is unknown. His mother's first name was Katherine, but her maiden name is also unknown. A later lawsuit establishes that he had a sister named Helen. His birthplace is also unknown, although more than a century after Tarlton's death Thomas Fuller said that he was born at Condover in Shropshire, where his father was a pig farmer, and that the family later moved to Ilford in Essex.[1]

Career

editTradition claims that Tarlton started his career in London as either an apprentice, a swineherd in Ealing, or a water-carrier; it is not impossible that he was all three.[2] By 1583, when he is mentioned as one of the original members of the Queen's Men, he was already an experienced actor.[3]

He was an early yet extraordinary influence on Elizabethan clowns. His epitaph says: "he of clowns to learn still sought/ But now they learn of him they taught". Tarlton was the first to study natural fools and simpletons to add knowledge to his characters. His manner of performance combined the styles of the medieval Vice, the professional minstrel, and the amateur Lord of Misrule. During the play, he took it upon himself to police hecklers by delivering a devastating rhyme when necessary. He would spend time after the play in a battle of wits with the audience. He worked with Queen Elizabeth's Men at the Curtain Theatre at the beginning of their career in 1583. The 1600 publication Tarlton's Jests tells how Tarlton, upon his retirement, recommended Robert Armin take his place.[4]

He was Queen Elizabeth's favourite clown. He had a talent for improvising doggerel on subjects suggested by his audience; in fact, improvised doggerel verse became known for a time as "Tarltons".[5] To cash in on his popularity, a great number of songs and witticisms of the day were attributed to him, and after his death the text Tarlton's Jests, containing many jokes in fact older than he was, made several volumes. Other books, and several ballads, coupled his name with their titles. Some have suggested that the evocation of Yorick in Hamlet's soliloquy was composed in memory of Tarlton.[3]

In addition to his other talents, Tarlton was a fencing master.[5] He wrote at least one play, The Seven Deadly Sins (1585); though it was enormously popular in its day, no copy has survived. Besides ballads and a play, Tarlton wrote several pamphlets starting in the 1570s, one of which was A True report of this earthquake in London (1580). These were apparently genuine, though after his death a variety of other works were attributed to him as well. Gabriel Harvey refers to him as early as 1579, indicating that Tarlton had already begun to acquire the reputation that rose into fame in later years. That fame transcended the social limits that judged players to be little more than rogues.

Tarlton, according to one of his sons, gambled away the family's entire fortune. Tarlton lived in Drayton Manor House, Hanwell where he is rumoured to be buried.[citation needed] Drayton Manor is now Drayton Manor High School.[citation needed]

Tarlton made his last will on 3 September 1588, describing himself as "Richard Tarlton, one of the Grooms of the Queen's Majesty's Chamber". In the will he entrusted the son he had illegitimately fathered, Philip Tarlton, to the care of "my most loving mother, Katherine Tarlton, widow, and my very loving and trusty friends Robert Adams, gentleman, and my fellow, William Johnson, one also of the Grooms of her Majesty's Chamber".[6] He died on 5 September, at the home of Emma Ball, a "woman of bad reputation" and was buried the same day at St Leonard's, Shoreditch.[5]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Thomson 2004.

- ^ Richard Dutton et al., eds., Hanwell Shakespeare, p. 24.

- ^ a b Chisholm 1911.

- ^ Chettle, Tarlton's Jests: and News out of purgatory The forgeries by John Payne Collier had not yet been exposed when this 1844 edition of Tarlton's Jests: and News out of purgatory was published. Therefore this edition can’t be trusted when Collier is referred to, as he is several times in the introduction. And one of Collier’s forgeries is included in the edition, as though it were authentic, which it is not. It is titled “Tarlton’s Jiggs of a horse loade of Fooles", and appears in the introduction beginning on page xx.

- ^ a b c Stephen, Sir Leslie. Dictionary of National Biography, Volume 55. Macmillan. 1898. p. 370.

- ^ Honigmann 1993, p. 57.

Bibliography

edit- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Tarlton, Richard". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Honigmann, E.A.J. (1993). Playhouse Wills. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 57–8. ISBN 9780719030161. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- Carlyle, Edward Irving (1898). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 55. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Thomson, Peter (2004). "Tarlton, Richard (d. 1588)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/26971. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Dutton, Richard, Alison Gail Findlay, and Richard L. Wilson, eds. Lancastrian Shakespeare: Region, Religion, and Patronage. Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2004.

- Gurr, Andrew. The Shakespearean Stage 1574–1642. Third edition, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- Peter Thomson (17 June 2013). Shakespeare's Theatre. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-11364-2.