Sari Nusseibeh (Arabic: سري نسيبة) (born in 1949) is a Palestinian professor of philosophy and former president of the Al-Quds University in Jerusalem. Until December 2002, he was the representative of the Palestinian National Authority in that city. In 2008, in an open online poll, Nusseibeh was voted the 24th most influential intellectual in the world on the list of Top 100 Public Intellectuals by Prospect Magazine (UK) and Foreign Policy (United States).[1]

Sari Nusseibeh | |

|---|---|

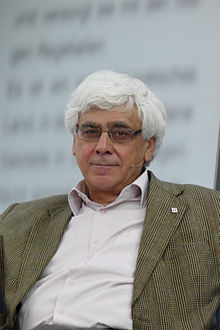

Sari Nusseibeh at 2012 Leipzig Book Fair | |

| President of Al-Quds University | |

| Palestinian National Authority Representative in Jerusalem | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1949 Damascus, Syria |

| Nationality | Palestinian |

| Spouse | Lucy Austin |

| Children | 4 |

| Alma mater | Christ Church, Oxford |

| Occupation | Professor of Philosophy |

Family background

The Nusseibeh boast of a 1,300 year presence in Jerusalem, being descended from Ubayda ibn as-Samit, the brother of Nusaybah bint Ka'ab, a female warrior from the Banu Khazraj of Arabia, and one of the four women leaders of the 14 tribes of early Islam. Ubadya, a companion of Umar ibn al-Khattab, was appointed the first Muslim high judge of Jerusalem after its conquest in 638 C.E., together with an obligation to keep the Holy Rock of Calvary clean.[2] Despite the noble origins, family tradition, in keeping with the belief that all great families have roots in brigandage, transmits a legend that their descent can also be traced through a long line of thieves.[3]

According to family tradition, they retained an exclusive right to the keys of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre down to the Ottoman period, when the Joudeh family obtained a warrant to share possession.[4] To this day, the Nusseibeh family are said to be trustees, and upon receiving the keys from a member of the Joudeh clan, the Nusseibeh are said to turn them over to the warden of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre around dawn every day.[5] Moshe Amirav reports Nusseibeh as quipping, nonetheless, when replying in the negative to a query about his family's possession of the keys, that:'No, there is no longer any need for it. Jesus isn't there any more.'[6]

Nusseibeh's grandfather successively married into three different Palestinian families of notables, the Shihabi, noted for their scholarship; the Darwish of the powerful al-Husayni family; and to the Nashashibi, and thus, in Nusseibeh's words: 'in a matter of a few years [...] managed to stitch together four ancient Jerusalem families, two of which were bitter rivals'.[7]

Biography

Nusseibeh was born in Damascus, Syria, to the politician Anwar Nusseibeh who was a distinguished statesman, prominent in Palestinian and (after 1948) Palestinian-Jordanian politics and diplomacy. His mother, Nuzha Al-Ghussein, daughter of Palestinian political leader Yaqub al-Ghusayn was born in Ramle,[8] into a family of wealthy landed aristocrats with land in Wadi Hnein (now the Israeli town of Nes Ziona),[9] His mother had left Palestine in 1948 to avoid the fighting, and his father lost a leg when wounded while participating in the 1947–48 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine.[10] They moved to Cairo some years later, where his father participated in the formation of the First Palestine Government in exile.[11] On returning to Jerusalem, he lived just a few hundred yards over the other side of No man's land from Amos Oz, and in reading the latter's memoir of his upbringing, was struck by the profound differences between their respective experiences as children in the same city.[12] Their family owned farmland in Karameh which he helped till by driving a tractor during summer vacations. It was to be the site of what in Palestinian memory became known as the bloodbath of their Palestinian Stalingrad.[13] During Israel's conquest of the West Bank in the Six-Day War, Israel troops sacked the family home in Jerusalem, looting it of all of their heirlooms, though the family car was later returned.[14] Some months later, the occupation authorities then expropriated the family's 200 acre country estate in the Jordan Valley.[15]

In the fall of 1967, Nusseibeh went to study philosophy at Christ Church, Oxford. There he became friends with Avishai Margalit, as well as Ahmad Walidi, the only other Palestinian undergraduate there at the time, and son of the distinguished scholar Walid Khalidi.[16][17] It was a period marked by student revolutionary upheavals and it was at this time that Ahmad introduced him to the intricacies of Palestinian political factions, parodied in Monty Python's The Life of Brian.[18] The summers he spent back in Jerusalem, where, in 1968 he began studying Hebrew did a stint of work at the HaZore'a kibbutz,[19] and, the following year, was on hand to help quench the flames caused by Australian Christian fundamentalist arsonist Michael Rohan when the latter tried to burn down the Al-Aqsa Mosque by setting alight Saladin's 1,000 year old Aleppo pulpit.[20]

At Oxford, Nusseibeh met Lucy Austin, the daughter of British philosopher J.L. Austin, and future founder of the NGO MEND. They were married in late 1973 by the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Sheikh Saad al-Din Jalal al-Alami, and their marriage gave them four children: three sons, Jamal, Absal, Buraq, and one daughter, Nuzha.[21] While at Oxford Sari was much drawn to the linguistic philosophy introduced by Ludwig Wittgenstein and developed by Austin. After completing his Oxford degree, he spent a year at the Warburg Institute in London, after hearing a lecture by Abdulhamid Sabra which attracted him to the study of the early Islamic school of Mu'tazilite logicians, the thought of Al-Ghazali and the subsequent discursive victory of the latter, as formulated by the Ash'ari school of theologians.[22]

After a brief period working in Abu Dhabi, Nusseibeh took up doctoral studies on the topic of Islamic Philosophy at from Harvard University, beginning in the fall of 1974, and gained his Ph.D. in (1978).[8][23] He returned to the West Bank in 1978 to teach at Birzeit University (where he remained as professor of philosophy until the university was closed from 1988 to 1990 during the First Intifada). At the same time, he taught classes in Islamic philosophy at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, Israel. Through the early 1980s, he helped to organize the teachers' union at Birzeit, and served three terms as president of the union of faculty and staff there. Nusseibeh is also co-founder of the Federation of Employees in the Education Sector for all of the West Bank.

Political activism

Sari Nusseibeh has long been viewed as a Palestinian moderate. In July 1987, Nusseibeh and Faisal Husseini met with Moshe Amirav, a member of Israel's Likud Party becoming the first prominent Palestinians to meet with a member of the Israeli right. Amirav was testing the waters for a group close to then prime minister Yitzhak Shamir on the possibility of making a historic pact with the PLO and Fatah.[24]

After years of working toward the establishment of a functioning Palestinian state alongside the state of Israel, Nusseibeh was by 2011 referring to the two-state solution as a "fantasy".[25] In What's A Palestinian State Worth? (Harvard University Press, 2011) he called for a "thought experiment" of a single state in which Israel annexed all the territories, and Palestinians would be "second-class citizens" with "civil but not political rights" in which "Jews could run the country while the Arabs could live in it."[26] This specific suggestion has been dismissed as "disingenuous".[27] During this time, Nusseibeh has been speaking of steps toward one version or another of a single-state solution, such as a binational state.[26][28]

The First Intifada

Nusseibeh was also an important leader during the First Intifada, authoring the Palestinian Declaration of Principles[29] and working to strengthen the Fatah movement in the West Bank; Nusseibeh helped to author the "inside" Palestinians' declaration of independence issued in the First Intifada, and to create the 200 political committees and 28 technical committees that were intended to as an embryonic infrastructure for a future Palestinian administration.

First Gulf War

Following the firing of Scud missiles at Tel Aviv, Nusseibeh worked with Israeli Peace Now on a common approach to condemn the killing of civilians in the war. But he was arrested and placed under administrative detention on 29 January 1991, effectively accused of being an Iraqi agent.[30] The arrest was then questioned by British and American officials, and the U.S. administration urged that he should either be charged or else the suspicion would be that the arrest was political. He was adopted as a prisoner of conscience by Amnesty International.[31] and letters of protest were written to The Times by academics including Peter Strawson, Isaiah Berlin and H. L. A. Hart.[32] Some Israelis said the move was designed to discredit Nusseibeh before international opinion.[30] Palestinians saw the arrest as a political warning that Israel did not intend to negotiate with any Palestinian leader, no matter how moderate. For example, Saeb Erekat of An-Najah University said: "This is a message to us Palestinian moderates. The message is, 'You can forget about negotiations after the war because we are going to make sure there is no one to talk to'". He was released without charge shortly after the end of the war, after 90 days of imprisonment in Ramle Prison.[33]

Peace initiatives and activities since 2000

Nusseibeh was not politically active during much of the Oslo Peace Process but was appointed as the PLO Representative in Jerusalem in 2001.[34] During this period Nusseibeh began to strongly suggest that Palestinians give up their Right of Return in exchange for a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.[35] A number of Palestinian organizations have strongly condemned his views on this issue.[36]

Nusseibeh criticised the militarization of the intifada in January 2002 and called for the renunciation of suicide bombings and the establishment of Palestine as a demilitarized state: "A Palestinian state should be demilitarized—not because that's what Israel demands, but in our own interest." Some senior Israel figures, such as Uzi Landau rebuffed the proposal as a trick.[37]

In 2002 Sari Nusseibeh and former Shin Bet director, Ami Ayalon published The People's Voice, an Israeli-Palestinian civil initiative that aims to advance the process of achieving peace between Israel and the Palestinians, and a draft peace agreement that called for a Palestinian state based on Israel's 1967 borders and for a compromise on the Palestinian Right of Return. The People's Voice Initiative was officially launched on June 25, 2003.

In 2002, Yasser Arafat appointed Nusseibeh as the PLO's representative in East Jerusalem, a position he assumed after the sudden death of Faisal Husseini.[34]

In 2008, Nusseibeh said that the quest for the two-state solution was floundering. He called on Palestinians to start a debate on the idea of a one-state solution.[38]

Affiliations

Nusseibeh is head and founder of the Palestinian Consultancy Group, co-founder and member of several Palestinian institutions including the Jerusalem Friends of the Sick Society, the Federation of Employees in the Education Sector in the West Bank, the Arab Council for Public Affairs, the Committee Confronting the Iron Fist, and the Jerusalem Arab Council. He is also on the advisory board of The International Center for Ethics, Justice and Public Life at Brandeis University.[39]

Internationally, Nusseibeh is a member of the McGill Middle East Program's Executive and Management Committees. In November 2007, following the publication of Once Upon a Country: A Palestinian Life, he traveled to Montreal, Canada, to lecture on the MMEP and his vision of peace.

See also

Endnotes

- ^ Prospect Magazine 2008.

- ^ Nusseibeh 2009, p. 18.

- ^ Nusseibeh 2009, p. 15.

- ^ Dekker & Medearis 2010, p. 175 The Joudeh family conserve a different version, according to which Saladin handed the keys over to their clan 10 days after his conquest of the Kingdom of Jerusalem from the Crusaders.Historic records attest to a transfer of the keys to a Muslim family, neutral to the contentious issue, when squabbling Christian families could not agree on the right of possession. (Masalha 2007, p. 108).

- ^ Nusseibeh 2009, pp. 15–20.

- ^ Amirav 2009, p. 200.

- ^ Nusseibeh 2009, p. 24

- ^ Jump up to: a b Remnick 2008, p. 332.

- ^ Nusseibeh 2009, p. 34.

- ^ Nusseibeh 2008, p. 198.

- ^ Nusseibeh 2008, p. 199.

- ^ Nusseibeh 2009, pp. 11–12

- ^ Nusseibeh 2009, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Nusseibeh 2009, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Nusseibeh 2009, pp. 109, 117, 136.

- ^ Nusseibeh 2009, p. 104

- ^ Benedikt 2004.

- ^ Nusseibeh 2009, pp. 104–105

- ^ Nusseibeh 2009, pp. 113–115.

- ^ Nusseibeh 2009, p. 118.

- ^ Nusseibeh 2012, pp. 130–132, 232.

- ^ Nusseibeh 2009, pp. 121–128.

- ^ Nusseibeh 2009, pp. 132–134.

- ^ Nusseibeh 2009, p. 253

- ^ Spiegel 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b El Moussaoui 2012.

- ^ Shulman 2012.

- ^ Nusseibeh 2014.

- ^ see Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 17, No. 3, Spring 1988, p.63–65 for the text of the Declaration of Principles, also known as the Fourteen Demands

- ^ Jump up to: a b King 2007, p. 180.

- ^ Amnesty International 1991.

- ^ Nusseibeh 2009, p. 163.

- ^ Nusseibeh 2009, pp. 314–321.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Eldar 2002.

- ^ [1] Archived May 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [2] Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ BBC 2002.

- ^ Ross, Oakland. Palestinians revive idea of one-state solution. The Toronto Star.

- ^ [3] Archived September 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

References

- Amirav, Moshe (2009). Jerusalem Syndrome: The Palestinian-Israeli Battle for the Holy City. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-845-19347-8.

- "Israel and the Occupied Territories: Dr. Sari Nusseibeh: prisoner of conscience held in administrative detention". Amnesty International. 21 March 1991. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- Avnery, Uri (September 5, 2010). "Uri Avnery on Sari Nusseibeh and the Two-State vs One-State Solution". Palestine-Mandate. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- "Arafat aide proposes demilitarised state". BBC News. BBC News. 13 January 2002. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- Benedikt, Linda (9 January 2004). "Interview with Sari Nusseibeh". Media Monitors Network. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Bird, Kai (2010). Divided City: Coming of Age Between the Arabs and Israelis. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780857200198.

- Dekker, Ted; Medearis, Carl (2010). Tea with Hezbollah: Sitting at the Enemies Table Our Journey Through the Middle East. Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-58829-6.

- DPA (May 27, 2005). "Union urges Al-Quds to fire Sari Nusseibeh". Haaretz. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- Eldar, Akiva (20 December 2002). "Arafat deposes Sari Nusseibeh as Jerusalem chief". Haaretz. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- Nusseibeh, Sari (6 September 2012). El Moussaoui, Naima (ed.). "Interview with Sari Nusseibeh: Plea for Radical Pragmatism". Qantara.de. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- isotalo, Riina (2007). "Palestinian return:Reflections on Unifying Discourses, Dispersing Practices and Residual narratives". In Benvenisti, Eyal; Gans, Chaim; Hanafi, Sari (eds.). Israel and the Palestinian Refugees. Beiträge zum ausländischen öffentlichen Recht und Völkerrecht. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 159–187. ISBN 978-3-540-68161-8.

- Killgore, Andrew I. (March 1991). "The True Crime of Palestinian Professor Sari Nusseibeh". Washington Report on Middle Eastern Affairs. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- King, Mary Elizabeth (2007). A Quiet Revolution: The First Palestinian Intifada and Nonviolent Resistance. Nation Books. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-786-73326-2. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- Lis, Jonathan; Regular, Arnon (29 April 2004). "Dr. Sari Nusseibeh arrested for hiring illegal Palestinian workers". Haaretz. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- Masalha, Nur (2007). The Bible and Zionism: Invented Traditions, Archaeology and Post-Colonialism in Palestine- Israel. Zed Books. ISBN 9781842777619.

- Nusseibeh, Sari (2000). "The Future of Jerusalem A Palestinian Perspective". In Ma'oz, Moshe; Nusseibeh, Sari (eds.). Jerusalem: points of friction, and beyond. BRILL. pp. 7–10. ISBN 978-90-411-8843-4. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- Nusseibeh, Sari (24 September 2001). "What next?". Haaretz. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- Nusseibeh, Sari (2008). "Negotiating the City: A perspective of a Jerusalemite". In Mayer, Tamar; Mourad, Suleiman A. (eds.). Jerusalem: Idea and Reality. Routledge. pp. 198–204. ISBN 978-1-134-10287-7.

- Nusseibeh, Sari (2009) [2007]. Once Upon A Country: A Palestinian Life. London: Halban Publishers. ISBN 978-1-905559-05-3. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- Nusseibeh, Sari (2012). What Is a Palestinian State Worth?. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-05949-8. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Nusseibeh, Sari (21 February 2012). Doerry, Martin; von Mittelstädt, Juliane (eds.). "A Palestinian Take on the Mideast Conflict: 'The Pursuit of a Two-State Solution Is a Fantasy'". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Nusseibeh, Sari (25 June 2014). "How Israel Can Avoid a Hellish Future". Haaretz. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- "Intellectuals—the results". Prospect Magazine. July 2008. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Remnick, David (2008). "Rage and reason:Saari Nusseibeh and the PLO". Reporting: Writings from the New Yorker. Pan Macmillan. pp. 330–344. ISBN 978-0-330-47129-9.

- Rubenberg, Cheryl (2003). The Palestinians: In Search of a Just Peace. Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-58826-225-7. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- Rubinstein, Danny (12 November 2001). "An Exception to the Rule". Haaretz. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- Wallach, John; Wallach, Janet (1994). The New Palestinians: The Emerging Generation of. Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-559-58429-6.

- Shulman, David (24 February 2012). "Israel & Palestine: Breaking the Silence". New York Review of Books. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Sylvia Murphy, Candy's Children (Novel) partially set in a remembered Palestine. (S.A.Greenland Imprint, 2007) ISBN 978-0-9550512-1-0

Published writings

Books

- No Trumpets, No Drums: A Two-State Solution of the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict, New York: Hill & Wang, 1991

- Once Upon a Country: A Palestinian Life, written with Anthony David; New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, London: Halban Publishers, 2007 ISBN 978-1-905559-05-3

- Palestine: A State is Born (Selections of Newspapers/Magazines articles between 1987-1990 ) Palestine Information Office :The Hague, 1990.

- What Is a Palestinian State Worth?. Harvard University Press. 2011. pp. 234. ISBN 978-0-674-04873-7.

- The Story of Reason in Islam. Stanford University Press, 2016. ISBN 978-0-804-79461-9

Other works

- A Formula for Narrative Selection: A Commentary on Writing the Arab- Israeli Conflict, Perspectives on Politics, Vol 3/No1 (March, 2005)

- The Limit Of Reason (or Why Dignity is not Negotiable), APA Newsletters, (Vo.04, Number1), 2004.

- Singularidad y pluralidad en la identidad: el caso del prisionero palestino, La Pluralidad y sus atributos (Fundacion Duques de Soria) 2002.

- Personal and National Identity: A Tale of Two Wills. Philosophical Perspectives on the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict, ed. Tomas Kapitan, (Armonk, N.Y., and London: Sharpe, N.E.) 1997.

- Epistemology, The Routledge History of Islamic Philosophy, ed. Oliver Leaman.( London: Routledge, Kegan and Paul), 1995.

- Al-Hurriyyah Bayn Alhadd Wa’l Mutlaq (Absolute and Restricted Freedom). London: Al-Saqi, 1995.

- Al-Hizb al-Siyasi Wa’l dimoqratiyyah (Political Parties and Democracy). In Azmat al-hizb al-Siyasi al-Falastini.( Ramallah: Muwatin) 1996

- Can Wars be Just? in But Was It Just? Reflections on the Morality of the Gulf War, with Jean Elshtaine, et al. (New York: Doubleday) 1992.

- Review of F. Zimmermann's Al-Farabi's Commentary and Short Treatise on Aristotle's De Interpretatione, History and Philosophy of Logic, 13 (1992), 115–132.

- Al-Aql Al Qudsi: Avicenna's Subjective Theory of Knowledge. Studia Islamica (1989), 39–54.

- Selections (including translations) from the Holy Qur'an. In Bartlett's Familiar Quotations, 15th ed., 1984.

- Review of Islamic Life and Thought, by S. A. Nasr.( TLS) March 1982:267.

- Masharif al-Mantiq (Introductory Symbolic Logic). (Jerusalem: Arab Studies Society) 1982.

- On Subatomic Particles and Scientific Posits, with Basheer El-Issa. (Birzeit Journal of Chemistry) 1981.

- Avicenna : Medicine and Scepticism. Koroth Vol.8, No 1- 2 (1981): 9-20.

- Quelques figures et themes de la Philosophie Islamique. Review in Asian and African Studies 14 (1980), 207–209.

- Herbert Marcuse wa’l metamarxiyyah." Al-Jadid, July 1

External links

- Sari Nusseibeh's web page

- NPR interview on Oct 18, 2001.

- One on One with Sari Nusseibeh: Once upon a conflict - interview with The Jerusalem Post 26 April 2007

- Haaretz interview, Aug. 15, 2008

- Biography at the Wayback Machine (archived October 28, 2009)

- Interview with Sari Nusseibeh "Human Values Unite, Religious Values Divide!" at the Wayback Machine (archived September 6, 2010)

- Symposium: Sari Nusseibeh's "What Is a Palestinian State Worth?", Reason Papers: A Journal of Interdisciplinary Normative Studies, October 2012, pp. 15-69