Seán McGarry (2 August 1886 – 9 December 1958) was a 20th-century Irish nationalist and politician.[1] A longtime senior member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), he served as its president from May 1917 until May 1918 when he was one of a number of nationalist leaders arrested for his alleged involvement in the so-called German Plot.

Seán McGarry | |

|---|---|

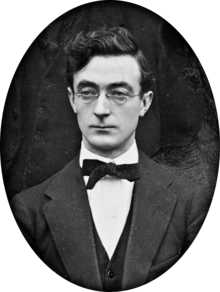

McGarry, c. 1915 | |

| Teachta Dála | |

| In office August 1923 – 30 October 1924 | |

| Constituency | Dublin North |

| In office May 1921 – June 1922 | |

| Constituency | Dublin Mid |

| President of the Irish Republican Brotherhood | |

| In office November 1917 – May 1919 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas Ashe |

| Succeeded by | Harry Boland |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 2 August 1886 Dundrum, Dublin, Ireland |

| Died | 9 December 1958 (aged 72) Dublin, Ireland |

| Political party | |

| Spouse | Tomasina McGarry |

| Children | 3 |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | |

| Battles/wars | |

Biography

editHe was born in number 17, Pembroke Cottages, Dundrum, Dublin in 1886. An active member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, McGarry was a close friend of Bulmer Hobson and was frequently arrested or imprisoned by British authorities for his activities with the IRB during the early 1900s. McGarry participated in the 1916 Easter Rising as an aide-de-camp to Tom Clarke[2] and sentenced to eight years penal servitude for his role in the failed rebellion.[3]

He was sent to Frongoch internment camp in Wales, but was eventually released. McGarry assisted Michael Collins in his efforts to reorganise the Irish Republican Brotherhood and, at the Volunteer Executive Meeting held in late 1917, he was elected General Secretary of the Irish Volunteers.[4][5]

On the night of 17 May 1918, McGarry was arrested, along with seventy-three other Irish nationalist leaders, and deported to England, where they were held in custody without charge. The day following their arrest, he and the others were charged with conspiring "to enter into, and have entered into, treasonable communication with the German enemy".[6] In his absence, Harry Boland was selected for the Supreme Council and became his successor as president of the IRB.[7]

He was only imprisoned a short time when he took part in the famous escape from Lincoln Jail with Seán Milroy and Éamon de Valera on 3 February 1919.[8] He and Milroy had managed to smuggle out a postcard, a comical sketch of McGarry to his wife, allowing a copy of the key to their cell to be made. They were later assisted by Harry Boland and Michael Collins who awaited them outside the prison.[9]

A month later, McGarry gave a dramatic speech at a Sinn Féin concert held at the Mansion House, Dublin before going into hiding.[10]

Throughout the Irish War of Independence, McGarry served as a commander and was eventually elected to Second Dáil in the 1921 elections as a Sinn Féin Teachta Dála (TD) representing Dublin Mid.[11] He, like the majority of those in the Irish Republican Brotherhood, supported the Anglo-Irish Treaty and was involved in debates against de Valera during the controversy, most especially discussing the status of Sinn Féin as a political entity.[12]

He was re-elected as a Pro-Treaty Sinn Féin TD in the 1922 general election, siding with the Free State government during the Irish Civil War. Liam Lynch and other members of the anti-Treaty IRA planned the assassination of McGarry among other TDs supporting the Public Safety Bill. As one anti-Treaty volunteer told Ernie O'Malley, "Seán McGarry was often drunk in Amiens St. and the boys wanted to shoot him and the Staters there but I wouldn't let them..."[13]

On 10 December 1922, shortly before the first meeting of the Free State parliament, a fire was deliberately set by irregulars (anti-Treatyites) at his family home. His seven-year-old son, Emmet, was badly burned and died as a result. Seán McGarry was one of four targeted by anti-Treatyites during the December Free State executions. De Valera publicly denounced the attack.[14][15]

McGarry was re-elected as a Cumann na nGaedheal TD in the 1923 general election for Dublin North. Dissatisfied and disillusioned with Cumann na nGeadhael, he resigned from the party after the Irish Army Mutiny and joined Joseph McGrath's National Party.[16] He resigned his seat in October 1924.[17][18]

After retiring from politics, he worked for the Irish Hospitals Trust.[1]

Gallery

edit-

British Army military intelligence file for Seán McGarry

-

Mugshot of Seán McGarry taken by Dublin Metropolitan Police circa 1916

Further reading

edit- De Búrca, Pádraig and John F. Boyle. Free State Or Republic?: Pen Pictures of the Historic Treaty Session of Dáil Éireann. Dublin: Talbot Press Ltd., 1922.

- Darrell Figgis: Recollections of the Irish War. New York: Doubleday, Doran & Co., 1928.

- Knirck, Jason K. Imagining Ireland's Independence: The Debates Over the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2006; ISBN 0-7425-4148-7

- O'Donoghue, Florence. No Other Law: The Story of Liam Lynch and the Irish Republican Army, 1916–1923. Dublin: Irish Press, 1954.

References

edit- ^ a b White, Lawrence William (October 2009). "McGarry, Seán". Dictionary of Irish Biography. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ My Fight for Ireland's Freedom, Kathleen Clarke, RP 1997; ISBN 0-86278-245-7, p. 75

- ^ McHugh, Roger Joseph. Dublin, 1916. London: Arlington Books, 1966. (pg. 206)

- ^ Hopkinson, Michael, ed. Frank Henderson's Easter Rising: Recollections of a Dublin Volunteer. Cork: Cork University Press, 1998 (p. 81); ISBN 1-85918-143-0

- ^ Bell, J. Bowyer. The Secret Army: The IRA. Somerset: Transaction Publishers, 1997 (p. 17) ISBN 1-56000-901-2

- ^ Tansil, Charles. America and the Fight for Irish Freedom 1866–1922. New York: Devin-Adir Co., 2007. (pp. 254-56)

- ^ Fitzpatrick, David. Harry Boland's Irish Revolution. Cork: Cork University Press, 2003 (p. 114) ISBN 1-85918-386-7

- ^ Macardle, Dorothy (1965). The Irish Republic. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 283.

- ^ Brown, Darren. The Greatest Escape Stories Ever Told: Twenty-five Unforgettable Tales. Guilford, Connecticut: Globe Pequot, 2002. (p. 153); ISBN 9781592284801

- ^ McConville, Sean. Irish political offenders, 1848–1922: Theatres of War. New York: Routledge, 2003. (p. 644) ISBN 0-415-21991-4

- ^ "Seán McGarry". Oireachtas Members Database. Retrieved 9 December 2008.

- ^ Laffin, Michael. The Resurrection of Ireland: The Sinn Féin Party, 1916–1923. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 1999. (p. 367); ISBN 0-521-65073-9

- ^ Hopkinson, Michael, ed. Frank Henderson's Easter Rising: Recollections of a Dublin Volunteer. Cork: Cork University Press, 1998 (pp. 7–8); ISBN 1-85918-143-0

- ^ Valiulis, Maryann Gialanella. Portrait of a Revolutionary: General Richard Mulcahy and the Founding of the Irish Free State. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1992. (pp. 183–184); ISBN 0-8131-1684-8

- ^ Cathal, Liam. Blood on the Shamrock: A Novel of Ireland's Civil War, 1916–1921. Cincinnati: St. Padriac Press, 2006. (pg. xlvi)

- ^ Manning, Maurice and Moore McDowell. Electricity Supply in Ireland: The History of the ESB. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan, 1984 (p. 70)

- ^ "Seán McGarry". ElectionsIreland.org. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

- ^ Coogan, Tim Pat. De Valera: Long Fellow Long Shadow. London: Hutchinson, 1995.