Snakes (also known as serpents) are an important motif in Chinese mythology. There are various myths, legends, and folk tales about snakes. Chinese mythology refers to these and other myths found in the historical geographic area(s) of China. These myths include Chinese and other languages, as transmitted by Han Chinese as well as other ethnic groups (of which fifty-six are officially recognized by the current administration of China).[1]

Snakes often appear in myth, religion, legend, or tales as fantastic beings unlike any possible real snake, often having a mix of snake with other body parts, such as having a human head, or magical abilities, such as shape-shifting. One famous snake that was able to transform back and forth between a snake and a human being was Madam White Snake in the Legend of the White Snake.

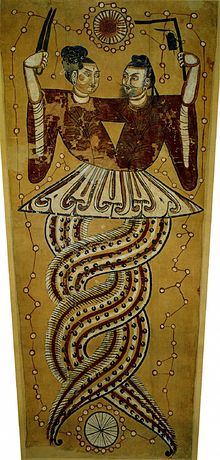

Other snakes or snake-like beings sometimes include deities, such as Fuxi and Nüwa and Gong Gong. Sometimes, Fuxi and Nuwa are described as snakes with human heads and sometimes as humans with dragon or serpent tails.

Myth versus history

editIn the study of historical Chinese culture, many of the stories that have been told regarding characters and events which have been written or told of the distant past have a double tradition: one tradition which presents a more historicized and one which presents a more mythological version.[2]

Snake-like deities

editRiver deities

editIn ancient China, some of the river gods which were worshiped were depicted in the form of some sort of snake or snake-like being:[3]

Directional deities of the north

editIn the ancient China of the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), worship of Four Directional deities developed, the directions were east, south, west, and north. With the direction of the middle, there were five major directions, each associated with a divine being or beings, a season, and a color (with the "middle direction" being associated with the emperor and the color yellow). This set of correlations of five whatevers included many more than mentioned here, in the elaborated philosophical system of Wǔ Xíng (五行), although some of the basics related to directional deities was much older.

The north was associated with a pair of divine beings, the Dark Warrior (Xuán Wǔ, 玄武), a tortoise-and-snake creature, with the season of winter, and with the color black[4] (also often considered to be a deepish shade of blue). Each of the directions was also associated with one of the wǔ xíng, or five "elements" (sometimes also translated as "phases" or "materials"): that of the north was water.

According to Anthony Christie, the tortoise-and-snake combination was known as the Black Warrior. And, that although the worship of the other directions was an ancient practice, the worship of the north was usually avoided because the north was considered the dwelling place of a destructive deity of the ocean wind. However, the worship of the north was practiced, with sacrificial ceremonies to the Black Warrior, by the rulers of the Han dynasty, which claimed to rule with the protection of water and the north.[5] Although the Black Warrior is generally depicted as a snake entwining around a turtle, sometimes, they are viewed as two separable generals.[6]

Deities from snake

editBai Suzhen and Xiaoqing became deities from snakes.[7]

The nine-headed baby

editIn Chinese mythology, Jiuying (九嬰, "the nine-headed baby") is an ancient monster with nine snake-like heads, capable of spouting water and breathing fire. Its name comes from its cry, which resembles a baby’s wail. During the reign of Emperor Yao, when ten suns appeared in the sky and caused widespread suffering, Jiuying was among the creatures that terrorized the people. To protect them, Emperor Yao sent the divine archer Hou Yi, who shot and killed Jiuying near the fierce waters. The creature is mentioned in ancient texts such as the Huainanzi.[8]

Culture

editIn Chinese culture, mythologized snakes and snake-like beings have various roles, including the calendar system, poetry, and literature.

Zodiacal snake

editIn Chinese culture, years of the Snake are sixth in the cycle, following the Dragon Years, and recur every twelfth year. The Chinese New Year does not fall on a specific date, so it is essential to check the calendar to find the exact date on which each Snake Year actually begins. Snake years include: 1905, 1917, 1929, 1941, 1953, 1965, 1977, 1989, 2001, 2013, and 2025. The 12 "zodiacal" (that is, yearly) animals recur in a cycle of sixty years, with each animal occurring five times within the 60-year cycle, but with different aspects each of those 5 times. Thus, 2013 is a year of the yin water Snake, and actually starts on February 10, 2013 and lasts through January 30, 2014. The previous year of the yin water Snake was 1953.[9]

In Thai culture, the year of the Snake is instead the year of the little Snake, and the year of the Dragon is the year of the big Snake.

According to one mythical legend, there is a reason for the order of the 12 animals in the 12-year cycle. The story goes that a race was held to cross a great river, and the order of the animals in the cycle was based upon their order in finishing the race. In this story, the Snake compensated for not being the best swimmer by hitching a hidden ride on the Horse's hoof, and when the Horse was just about to cross the finish line, jumping out, scaring the Horse, and thus edging it out for sixth place.[citation needed]

The same 12 animals are also used to symbolize the cycle of hours in the day, each being associated with a two-hour time period. The "hour" of the Snake is 9:00 to 11:00 a.m., the time when the sun warms up the earth, and Snakes slither out of their holes.

The reason the animal signs are referred to as "zodiacal" is because a person's personality is said to be influenced by the animal sign(s) ruling the time of birth, together with elemental aspect of that animal sign within the sexegenary (60 year) cycle. Similarly, the year governed by a particular animal sign is supposed to be characterized by it, with the effects particularly strong for people who were born in a year governed by the same animal sign.[9]

Characters

editThe usual and general Chinese word and character for Snake is shé (Chinese: 蛇; pinyin: shé; lit. 'Snake or Snakes'). As a zodiacal sign, the Snake is associated with Chinese: 巳; pinyin: sì, a proper noun referring to the 6th of the 12 Earthly Branches, or to the double-hour of 9-00-11:00 a.m.

The Five Noxious Creatures

editOn the fifth day of the fifth month of the Chinese calendar is the festival of the Double Fifth (Duanwu). Many of the activities traditional on this holiday involve expelling various sources of potential evil influences. One of these involves driving away the Five Noxious Creatures (wu du), of which the Snake is one.[10]

Real and legendary

editSome reports of fantastic snakes may belong more properly to the field of cryptozoology, legend, or folktale, rather than mythology or religion.

An example of this, is the "sudden striker" snake of Sunzi's Art of War that was supposed to be able to fight with both head and tail, and was used as a simile for how a general who is expert at military deployment does so. The Sudden Striker snake supposedly lived on "Mount Ch'ang": (Roger T. Ames believes this to have been Mount Heng, but written with a different character to avoid a naming taboo on the given name of Han Wendi).[11]

Other snake-like or reptilian creatures

editOther members of certain types of Chinese dragon are considered especially snake-like, such as the Teng, which is sometimes known as the "flying snake-dragon". Some reptilians are not at all snake-like, such as the Ao.[12]

See also

editGeneral

editSpecific

edit- Bāshé (巴蛇), giant, elephant-eating snake.

- Chī (螭) or chīlóng (螭龍), a "hornless dragon".

- Chinese dragon, Chinese dragons tend toward snake taxonomy.

- Chì-sōng-zǐ (赤松子), sometimes said to have a serpent-endowed concubine.

- Gǔ (蠱), including use of snake-venom.

- Marquis of Sui's pearl, also known as Suí-Hóu-Zhū (隨侯珠), an amazing luminous pearl given to a ruler of Sui state by a grateful snake whose life he had saved.

- Nāga (那伽), in China, generally more considered to be a dragon.

- Snake-wine (shé-jiǔ, 蛇酒), a type of wine with alleged medicinal or tonic qualities.

- Xiāngliǔ (Xiāng-Liǔ, 相柳), also known as Xiāngyáo (Xiāng-Yáo, 相繇), a nine-headed snake or dragon.

- Zhúlóng (燭龍), also known as Zhúyīn (燭陰), a divine torch-dragon.

Notes

edit- ^ Yang, 2005: page 4

- ^ Yang, 2005: pages 12–13

- ^ Eberhard: 2003[1986], page 268

- ^ Christie, 1968: page 46

- ^ Christie, 1968: pages 82–83

- ^ Uschan, Michael V. (9 May 2014). Chinese Mythology. Greenhaven Publishing LLC. ISBN 978-1-4205-1146-8.

- ^ "全台唯一白蛇廟 小龍年到香火盛│TVBS新聞網". TVBS (in Chinese). 26 January 2013.

- ^ 淮南子 (in Chinese). 一個人. 28 July 2015. p. 43.

- ^ a b 2016 Snake Feng Shui Guide & Chinese Zodiac Forecast. Book Book.

- ^ Eberhard: 2003[1986], "Noxious Creatures, The Five", pages 208–209

- ^ Ames, 1993: page 158 and note 200 on page 294

- ^ "Guiguzi," China's First Treatise on Rhetoric: A Critical Translation and Commentary. SIU Press. 19 August 2016. ISBN 978-0-8093-3526-8.

References

edit- Ames, Roger, translation, introduction, and comments. (1993). Sunzi, et al. The Art of Warfare: The First English Translation Incorporating the Recently Discovered Yin-ch'üeh-shan Texts. (New York:Ballantine Books). ISBN 0-345-36239-X

- Christie, Anthony (1968). Chinese Mythology. Feltham: Hamlyn Publishing. ISBN 0600006379.

- Eberhard, Wolfram (2003 [1986 (German version 1983)]), A Dictionary of Chinese Symbols: Hidden Symbols in Chinese Life and Thought. London, New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-00228-1

- Hawkes, David, translation, introduction, and notes (2011 [1985]). Qu Yuan et al., The Songs of the South: An Ancient Chinese Anthology of Poems by Qu Yuan and Other Poets. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-044375-2

- Yang, Lihui, et al. (2005). Handbook of Chinese Mythology. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533263-6

- Yu, Anthony C., editor, translator, and introduction (1980 [1977]). The Journey to the West. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-97150-6