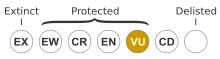

Synemon plana, commonly known as the golden sun moth, is a diurnal moth native to Australia and throughout its range, it is currently classified as vulnerable under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.[1]

| Synemon plana | |

|---|---|

| |

| Synemon plana male (left) and female (right) | |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Lepidoptera |

| Family: | Castniidae |

| Genus: | Synemon |

| Species: | S. plana

|

| Binomial name | |

| Synemon plana Walker, 1854

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Taxonomy

editA description of the species was published in 1854 (Lepidoptera: Castniidae), as a medium-sized (wingspan 31–34 mm), day-flying moth species.[2] Up until recently, the species had been listed as critically endangered, attracting the status of a flagship species towards the conservation of natural temperate grassland.[3]

Description

editThe golden sun moth is a medium sized, day-flying moth with distinct green eyes and clubbed antennae. The antennae are a notable feature of Synemon plana; as most other moths have brushy antennae. Listed as vulnerable under the EPBC Act 1999,[1] it is synonymous with Rytidosperma species of grasses and is almost completely confined to grasslands which include many of these grass species. At least a 40% cover of Rytidosperma species is optimal for the species.[4]

Male Synemon plana are dull in colour, the forewings consisting of dark brown, patterned with pale grey and the hind wings are brown with darker brown patches.[2] Female Synemon plana are brighter in colour with the forewings of brown and grey patterns,

the forewings are a bright golden brown colouring with dark brown patches on the outer margin of the hindwings. This golden colouring gives Synemon plana its common name, the golden sun moth.[3] Female Synemon plana are generally flightless, with small hindwings in comparison to the male.

Life cycle

editThe life cycle of the golden sun moth is relatively well understood. Longevity is estimated to be about two years (Edwards 1994), however, genetic evidence suggests that generation time may actually be 12 months (Clarke 1999). After mating, it is believed that the females lay up to 200 eggs at the base of the Rytidosperma tussocks. The eggs hatch after 21 days. The larvae tunnel underground while feeding before digging a vertical tunnel to the surface, where the pupa remains for six weeks until maturation. Adult moths emerge from the soil between the end of October and mid January and are only active during the hottest part of the day (most males are only active at temperatures above 22 °C).[3] At this larval stage, the moth remains underground for two to three years, feeding on the roots of native perennial grasses including speargrass (Austrostipa spp.), wallaby grass (Rytidosperma spp.) and Bothriochloa. This is based on evidence of case pupa shells and tunnels connecting to nearby tussocks. Recent discoveries suggest that the larvae may also feed on introduced grass species, with the presence of cast pupa shells protruding from the introduced Chilean needle grass (Nassella neesiana) tussocks.

The immature stages of the golden sun moth have not yet been described. Possible variation in the length of the larval stage of the golden sun moth may create the flexibility needed for a population to survive harsh years. When females emerge from the tunnel as adults, they already possess fully developed eggs, and begin to search for a mate, flashing the vivid orange hindwings to attract the attention of patrolling males.

Adults only live for one to two days, as they lack functional mouthparts and are unable to feed.[3]

Distribution

editThe golden sun moth endemic to Australia, is primarily confined in south-eastern native temperate grasslands which possess a high density of wallaby grasses (e.g. Rytidosperma spp.).[5]

Historically, the golden sun moth maintained a wide and likely continuous distribution in native temperate grasslands and open grassy woodlands at the time of European settlement, occurring across areas with highly dense populations of wallaby grasses.[3] Moth populations occurred in New South Wales (NSW) from Winburndale, near Bathurst, on the Yass Plains and south across large areas of the Australian Capital Territory (ACT). They were historically recorded in Victoria over vast areas surrounding Bendigo, Mansfield, Eildon, Nhill, Williamstown and Salisbury, to Bordertown in South Australia. Today, only around one per cent of the two million hectares of native temperate grasslands remain due to agricultural conversion, with weeds dominating much of this area.[6]

Currently, golden sun moth populations have reduced, becoming highly fragmented, with there being 125 known sites throughout its range post-1990.[3] This includes 48 occurring in NSW, 45 in Victoria and 32 in the ACT where majority of these populations do not exceed 5 hectares in area.[3]

Habitat

editPotential habitat for the moth includes any areas which have or once had grassy woodlands or native grasslands throughout the historical range of the species. The golden sun moth has been known to inhabit substantially degraded grasslands, including those dominated by the introduced Chilean needlegrass (Nassella neesiana). Two threatened ecological vegetation communities listed under the EPBC Act are known habitat sources for the moth – the ‘Natural Temperate Grassland of the Southern Tablelands of NSW and the ACT', and the ‘Natural Temperate Grassland of the Victorian Volcanic Plain’ (see EPBC Act Policy Statement 3.8).

Conservation Listing

editAs of December 7, 2021, under the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act), the golden sun moth is listed as vulnerable.[1][7] It has also been listed as a vulnerable taxon under the Victorian Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 and the New South Wales Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016. [7] It is also listed as endangered under the Australian Capital Territory Nature Conservation Act 2014.[7] The golden sun moth national recovery plan is in preparation by the NSW Department of Environment and Climate Change. [citation needed]

Conservation

editGolden sun moth populations have undergone substantial surveying and study, including through mitochondrial DNA analysis and allonym electrophoresis.[8][9][6] Conventional management actions for the species have included measures to improve habitat quality for the golden sun-moth, via the re-establishment of native grasses, weed and biomass removal, as well as efforts to reduce their mortality rates through predator control.[10][11] In environments where remnant habits co-exist with urban, management using a biodiversity sensitive urban design has been explored.[11]

Sightings

editIn January 2021, a moth was sighted and photographed by a man walking his dog in Wangaratta, Victoria.[12] The sighting was considered significant due to its distance from previously established populations, which was described as being "(...) The first sighting for sure within cooee of Wangaratta".

Threats and Impacts

editThe major threat to existing golden sun moth populations is the loss and degradation of grassland habitat and the subsequent changes in vegetative composition.[5] Predation, frequent and/or intense fire and their small, isolated and fragmented populations are also likely threats.[3] The native grasslands and grassy woodlands habitat of the moth are the most threatened of all vegetation types in Australia, with an estimated 99.5% being heavily altered or destroyed.[4][5] The integrity of this minuscule remaining native grassland has been impacted further by introduced pasture grasses and clovers, outcompeting the native Austrostipa and Rytidosperma species, as well as contributing to other ramifications. Predation from birds including the willie wagtail (Rhipidura leucophyrs), starling (Sturnus vulgaris), magpie lark (Grallina cyanoleuca) and welcome swallow (Hirundo neoxena), as well as predatory insects such as the robber fly (Asilidae) can contribute to adult golden sun moth mortality. While the golden sun moth is locally abundant at many small patches, majority of these sites are public areas and therefore, at risk to disturbance. The fragmentation and isolation of these populations further prohibits the ability for relatively immobile females to recolonise areas, reducing genetic change.[3][8]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c Conservation Advice for Synemon plana (Golden Sun Moth) (PDF). Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment. 2021.

- ^ a b Clarke, Geoffrey M. (2000-10-12), "Inferring demography from genetics: a case study of the endangered golden sun moth, Synemon plana", Genetics, Demography and Viability of Fragmented Populations, Cambridge University Press, pp. 213–226, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511623448.015, ISBN 978-0-521-78207-4

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Richter, Anett; Osborne, Will; Hnatiuk, Sarah; Rowell, Alison (2013-09-12). "Moths in fragments: insights into the biology and ecology of the Australian endangered golden sun moth Synemon plana (Lepidoptera: Castniidae) in natural temperate and exotic grassland remnants". Journal of Insect Conservation. 17 (6): 1093–1104. doi:10.1007/s10841-013-9589-1. ISSN 1366-638X.

- ^ a b O'Dwyer, C. & P.M. Attiwill (1999). "A comparative study of habitats of the Golden Sun Moth Synemon plana Walker (Lepidoptera: Castniidae): implications for restoration". Biological Conservation. 89 (2): 131–142. Bibcode:1999BCons..89..131O. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(98)00157-8.

- ^ a b c Kutt, A. S.; McKenzie, V. J.; Wills, T. J.; Retallick, R. W. R.; Dalton, K.; Kay, N.; Melero-Blanca, E. (2014-08-12). "Spatial and temporal determinants of golden sun mothSynemon planadistribution". Austral Ecology. 40 (1): 100–107. doi:10.1111/aec.12181. ISSN 1442-9985.

- ^ a b Gibson, L.; New, T. R. (2006-11-17). "Problems in studying populations of the golden sun-moth, Synemon plana (Lepidoptera: Castniidae), in south eastern Australia". Journal of Insect Conservation. 11 (3): 309–313. doi:10.1007/s10841-006-9037-6. ISSN 1366-638X.

- ^ a b c Department of the Environment (2022). "Species Profile and Threats Database Synemon plana - Golden Sun Moth". Canberra: Department of Environment.

- ^ a b Clarke, Geoffrey M.; O'Dwyer, Cheryl (March 2000). "Genetic variability and population structure of the endangered golden sun moth, Synemon plana". Biological Conservation. 92 (3): 371–381. Bibcode:2000BCons..92..371C. doi:10.1016/s0006-3207(99)00110-x. ISSN 0006-3207.

- ^ Clarke, Geoffrey M.; Whyte, Liam S. (2003). "Phylogeography and population history of the endangered golden sun moth (Synemon plana) revealed by allozymes and mitochondrial DNA analysis". Conservation Genetics. 4 (6): 719–734. Bibcode:2003ConG....4..719C. doi:10.1023/b:coge.0000006114.33543.32. ISSN 1566-0621.

- ^ Douglas, Fabian (June 2004). "A dedicated reserve for conservation of two species of Synemon (Lepidoptera: Castniidae) in Australia". Journal of Insect Conservation. 8 (2–3): 221–228. doi:10.1007/s10841-004-1354-z. ISSN 1366-638X.

- ^ a b Mata, Luis; Garrard, Georgia E.; Kutt, Alex S.; Wintle, Bonnie C.; Chee, Yung En; Backstrom, Anna; Bainbridge, Brian; Urlus, Jake; Brown, Geoff W.; Tolsma, Arn D.; Yen, Alan L.; New, Timothy R.; Bekessy, Sarah A. (2016-09-06). "Eliciting and integrating expert knowledge to assess the viability of the critically endangered golden sun-moth Synemon plana". Austral Ecology. 42 (3): 297–308. doi:10.1111/aec.12431. hdl:11343/291697. ISSN 1442-9985.

- ^ Critically endangered golden sun moth found by man walking dog in Wangaratta, Jackson Peck, ABC News Online, 2021-02-01