Taivoan or Taivuan, is a Formosan language spoken until the end of the 19th century by the indigenous Taivoan people of Taiwan. Taivoan used to be regarded as a dialect of Siraya, but now more evidence has shown that they should be classified as separate languages.[1] The corpora previously regarded as Siraya like the Gospel of St. Matthew and the Notes on Formulary of Christianity translated into "Siraya" by the Dutch people in the 17th century should be in Taivoan majorly.[2]

| Taivoan | |

|---|---|

| Rara ka maka-Taivoan | |

| Pronunciation | [taivu'an] |

| Native to | Taiwan |

| Region | Southwestern, around present-day Tainan, Kaohsiung. Also among some migration communities along Huatung Valley. |

| Ethnicity | Taivoan |

| Extinct | end of 19th century; revitalization movement |

Austronesian

| |

| Latin (Sinckan Manuscripts), Han characters (traditional) | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | tvx |

| Glottolog | taiv1237 |

| Linguasphere | 30-FAA-bb |

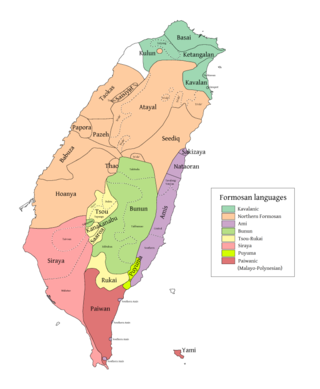

(pink) Taivoan | |

| Coordinates: 23°06′N 120°27′E / 23.100°N 120.450°E | |

Since the January 2019 code release, SIL International has recognized Taivoan as an independent language and assigned the code tvx.[3]

Classification

editThe Taivoan language used to be regarded as a dialect of Siraya. However, more evidences have shown that it belongs to an independent language spoken by the Taivoan people.

Documentary evidence

editIn "De Dagregisters van het Kasteel Zeelandia" written by the Dutch colonizers during 1629–1662, it was clearly said that when the Dutch people would like to speak to the chieftain of Cannacannavo (Kanakanavu), they needed to translate from Dutch to Sinckan (Siraya), from Sinckan to Tarroequan (possibly a Paiwan or a Rukai language), from Tarroequan to Taivoan, and from Taivoan to Cannacannavo.[4][5]

"...... in Cannacannavo: Aloelavaos tot welcken de vertolckinge in Sinccans, Tarrocquans en Tevorangs geschiede, weder voor een jaer aengenomen" — "De Dagregisters van het Kasteel Zeelandia", pp.6–8

Linguistic evidence

editA comparison of numerals of Siraya, Taivoan (Tevorangh dialect), and Makatao (Kanapo dialect) with Proto-Austronesian language show the difference among the three Austronesian languages in southwestern Taiwan in the early 20th century:[6][7]

| PAn | Proto-Siraya | Siraya | Mattauw | Taivoan | Makatao | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UM | Gospel | Kongana | Tevorangh | Siaurie | Eastern | Kanapo | Bankim | ||||

| 1 | *asa | *saat | sa-sat | saat | sasaat | isa | caha' | sa'a | caca'a | na-saad | saat |

| 2 | *duSa | *ðusa | sa-soa | ruha | duha | rusa | ruha | zua | raruha | ra-ruha | laluha |

| 3 | *telu | *turu | tu-turo | turo | turu | tao | toho | too | tatoo | ra-ruma | taturu |

| 4 | *Sepat | *səpat | pa-xpat | xpat | tapat | usipat | paha' | sipat, gasipat | tapat | ra-sipat | hapat |

| 5 | *lima | *rǐma | ri-rima | rima | tu-rima | hima | hima | rima, urima | tarima | ra-lima | lalima |

| 6 | *enem | *nəm | ni-nam | nnum | tu-num | lomu | lom | rumu, urumu | tanum | ra-hurum | anum |

| 7 | *pitu | *pitu | pi-pito | pito | pitu | pitu | kito' | pitoo, upitoo | tyausen | ra-pito | papitu |

| 8 | ---

*walu |

*kuixpa

--- |

kuxipat

--- |

kuixpa

--- |

pipa

--- |

vao

--- |

kipa'

--- |

---

waru, uwaru |

rapako | ---

ra-haru |

tuda |

| 9 | ---

*Siwa |

*ma-tuda

--- |

matuda

--- |

matuda

--- |

kuda

--- |

siva

--- |

matuha

--- |

---

hsiya |

ravasen | ---

ra-siwa |

--- |

| 10 | --- | *-ki tian | keteang | kitian | keteng | masu | kaipien | --- | kaiten | ra-kaitian | saatitin |

In 2009, Li (2009) further proved the relationship among the three languages, based on the latest linguistic observations below:

| PAn | Siraya | Taivoan | Makatao | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sound change (1) | *l | r | Ø~h | r |

| Sound change (2) | *N | l | l | n |

| Sound change (3) | *D, *d | s | r, d | r, d |

| Sound change (4) | *k *S |

-k- -g- |

Ø Ø |

-k- ---- |

| Morphological change (suffices for future tense) |

-ali | -ah | -ani |

| PAn | Siraya | Taivoan | Makatao | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sound change (1) | *telu | turu | toho | toru | three |

| *lima | rima | hima | rima | five, hand | |

| *zalan | darang | la'an | raran | road | |

| *Caŋila | tangira | tangiya | tangira | ear | |

| *bulaN | vural | buan | buran | moon | |

| *luCuŋ | rutong | utung | roton | monkey | |

| ruvog | uvok, huvok | ruvok | cooked rice | ||

| karotkot | kau | akuwan | river | ||

| mirung | mi'un'un | mirun | to sit | ||

| meisisang | maiyan | mairang | big | ||

| mururau | mo'owao, mowaowao | ----- | to sing | ||

| Sound change (2) | *ma-puNi | mapuli | mapuri | mapuni | white |

| tawil | tawin | tawin | year | ||

| maliko | maniku | maneku | sleep, lie down | ||

| maling | manung | bimalong | dream | ||

| *qaNiCu | litu | anito | ngitu | ghost | |

| paila | paila | paina | buy | ||

| ko | kuri, kuli | koni | I | ||

| Sound change (3) | *Daya | saya | daya | raya | east |

| *DaNum | salom | rarum | ralum | water | |

| *lahud | raus | raur | ragut, alut | west | |

| sapal | rapan, hyapan | tikat | leg | ||

| pusux | purux | ----- | country | ||

| sa | ra, da | ra, da | and | ||

| kising | kilin | kilin | spoon | ||

| hiso | hiro | ----- | if | ||

| Sound change (4) | *kaka | kaka | aka | aka | elder siblings |

| ligig | li'ih | ni'i | sand | ||

| matagi-vohak | mata'i-vohak | ----- | to regret | ||

| akusey | kasay | asey | not have | ||

| Tarokay | Taroay | Tarawey | (personal name) |

Based on the discovery, Li attempted two classification trees:[2]

1. Tree based on the number of phonological innovations

- Sirayaic

- Taivoan

- Siraya–Makatao

- Siraya

- Makatao

2. Tree based on the relative chronology of sound changes

- Sirayaic

- Siraya

- Taivoan–Makatao

- Taivoan

- Makatao

Li (2009) considers the second tree (the one containing the Taivoan–Makatao group) to be the somewhat more likely one.

Criticism against Candidius' famous assertion

editTaivoan was considered by some scholars as a dialectal subgroup of the Siraya ever since George Candidius included "Tefurang" in the eight Siraya villages which he claimed all had "the same manners, customs and religion, and speak the same language."[9] However, American linguist Raleigh Ferrell reexaminates the Dutch materials and says "it appear that the Tevorangians were a distinct ethnolinguistic group, differing markedly in both language and culture from the Siraya." Ferrell mentions that, given that Candidius asserted that he was well familiar with the eight supposed Siraya villages including Tevorang, it's extremely doubtful that he ever actually visited the latter: "it is almost certain, in any case, that he had not visited Tevorang when he wrote his famous account in 1628. The first Dutch visit to Tevorang appears to have been in January 1636 [...]"[1]

Lee (2015) regards that, when Siraya was a lingua franca among at least eight indigenous communities in southwestern Taiwan plain, Taivoan people from Tevorangh, who has been proved to have their own language in "De Dagregisters van het Kasteel Zeelandia", might still need the translation service from Wanli, a neighbor community that shared common hunting field and also a militarily alliance with Tevorangh.[5]

Li noted in his "The Lingue Franche in Taiwan" that, Siraya exerted its influence over neighbouring languages in the southwestern plains in Taiwan, including Taivoan to the east and Makatao to the South in the 17th century, and became lingua franca in the whole area.[10]

Phonology

editThe following is the phonology of the language:[11]

Vowels

edit| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i ⟨i, y⟩ | u ⟨u⟩ | |

| Mid | e ⟨e⟩ | ə ⟨e⟩ | |

| Open | a ⟨a⟩ | o ⟨o⟩ |

Consonants

edit| Bilabial | Dental | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m ⟨m⟩ | n ⟨n⟩ | ŋ ⟨ng⟩ | ||||

| Plosive | voiceless | p ⟨p⟩ | t ⟨t⟩ | k ⟨k⟩ | ʔ ⟨'⟩ | ||

| voiced | b ⟨b⟩ | d ⟨d⟩ | g ⟨g⟩ | ||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f ⟨f⟩ | s ⟨s⟩ | x ⟨x⟩ | h ⟨h⟩ | ||

| voiced | v ⟨v⟩ | z ⟨z⟩ | |||||

| Affricate | unaspirated | t͡s ⟨c⟩ | |||||

| aspirated | t͡sʰ ⟨ts⟩ | ||||||

| Liquid | rhotic | r ⟨r⟩ | |||||

| lateral | l ⟨l⟩ | ||||||

| Approximant | w ⟨w⟩ | j ⟨y⟩ | |||||

It's likely that there were no /g/, /ts/, and /tsʰ/ in the 17th–19th century Taivoan, although Adelaar claims c preceding i or y be sibilant or affricate[12] and so could be /ts/ or /ʃ/. However, the three sounds appeared after the 20th century, especially in Tevorangh dialect in Siaolin, Alikuan, and Dazhuang, and also in some words in Vogavon dialect in Lakku, for example:[13][14]

- /g/: agang /a'gaŋ (crab), ahagang /aha'gaŋ/ or agaga' /aga'ga?/ (red), gupi /gu'pi/ (Jasminum nervosum Lour.), Anag /a'nag/ (the Taivoan Highest Ancestral Spirit), kogitanta agisen /kogitan'ta agi'sən/ (the Taivoan ceremonial tool to worship the Highest Ancestral Spirits), magun /ma'gun/ (cold), and agicin /agit͡sin/ or agisen /agisən/ (bamboo fishing trap).

- /t͡s/: icikang /it͡si'kaŋ/ (fish), vawciw /vaw't͡siw/ (Hibiscus taiwanensis Hu), cawla /t͡saw'la/ (Lysimachia capillipes Hemsl.), ciwla /t͡siw'la/ (Clausena excavata Burm. f.), and agicin /agit͡sin/ (bamboo fishing trap). The sound also clearly appears in a recording of the typical Taivoan ceremonial song "Kalawahe" sung by Taivoan in Lakku that belongs to Vogavon dialect.[15]

The digraph ts recorded in the early 20th century may represent /t͡sʰ/ or /t͡s/:

- /t͡sʰ/ or /t͡s/: matsa (door, gate), tabutsuk (spear), tsakitsak (arrow), matsihaha (to laugh), tsukun (elbow), atsipi (a sole of the foot), tsau (dog). Only one word is attested in Vogavon dialect in Lakku: katsui (pants, trousers).[6]

Some scholar in Formosan languages suggest it's not likely that /t͡sʰ/ and /t͡s/ appear in a Formosan language simultaneously, and therefore ts may well represent /t͡s/ as c does, not /t͡sʰ/.

Stress

editIt's hard to tell the actual stressing system of Taivoan in the 17th–19th century, as it's been a dormant language for nearly a hundred years. However, since nearly all the existing Taivoan words but the numerals pronounced by the elders fall on the final syllable, there has been a tendency to stress on the final syllable in modern Taivoan for language revitalization and education, compared to modern Siraya that the penultimate syllable is stressed.

Grammar

editPronouns

editThe Taivoan personal pronouns are listed below with all the words without asterisk being attested in corpora in the 20th century :

| Type of Pronoun | Independent | Nominative | Genitive | Oblique |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1s | iau | kuri | -ku | iyaw-an |

| 2s | imhu | ko | -ho | imhu-an |

| 3s | *teni | *ta teni | -tin | *tini-an |

| 1p.i | *imita | kita | *-(m)ita | *imita-n |

| 1p.e | *imian | *kame | *-(m)ian | *imian-an |

| 2p | imomi | kamo, kama | *-(m)omi | imomi-an |

| 3p | *naini | *ta naini | -nin | *naini-an |

Numerals

editTaivoan has a decimal numeral system as following:[6][12]

| 1 | tsaha' | 11 | saka |

| 2 | ruha | 12 | bazun |

| 3 | toho | 13 | kuzun |

| 4 | paha' | 14 | langlang |

| 5 | hima | 15 | linta |

| 6 | lom | 16 | takuba |

| 7 | kito' | 17 | kasin |

| 8 | kipa' | 18 | kumsim |

| 9 | matuha | 19 | tabatak |

| 10 | kaipien | 20 | kaitian |

| Examples of higher numerals | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | tu-tuhu kaipien | ||

| 60 | lo-lom kaipien | ||

| 99 | matuha kaipien ab ki matuha | ||

| 100 | ka'atuxan | ||

| 4,000 | paha' katununan | ||

| 5,000 | hima katununan | ||

Examples

editWords and phrases

editSome Taivoan people in remote communities like Siaolin, Alikuan, Laolong, Fangliao, and Dazhuang, especially the elders, still use some Taivoan words nowadays, such as miunun "welcome" (originally "please be seated"), mahanru (in Siaolin, Alikuan), makahanru (in Laolong) "thank you", "goodbye" (originally "beautiful"), tapakua "wait a moment".[13]

Songs

editMany Taivoan songs have been recorded and some ceremonial songs like "Kalawahe" and "Taboro" are still been sung during every Night Ceremony annually. Some examples are:

Kalawahe (or "the Song out of the Shrine")[16]

edit- Wa-he. Manie, he mahanru e, he kalawahe, wa-he.

- Talaloma e, he talaloma e, he kalawahe, wa-he.

- Tamaku e, he tamaku e, he kalawahe, wa-he.

- Saviki e, he saviki e, he kalawahe, wa-he.

- Rarom he, he rarom he, he kalawahe, wa-he.

Panga (or "the Song of Offerings")

edit- Ho i he, rarom mahanru ho i he, rarom taipanga ho i he.

- Ho i he, hahu mahanru ho i he, hahu taipanga ho i he.

- Ho i he, hana mahanru ho i he, hana taipanga ho i he.

- Ho i he, saviki mahanru ho i he, saviki taipanga ho i he.

- Ho i he, iruku mahanru ho i he, tuku taipanga ho i he.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Based on the Siraya vocabulary found in the Utrecht Manuscript written in the 17th century.

- ^ Based on the Siraya vocabulary found in the Gospel of St. Matthew written in the 17th century.

- ^ Attested in Siraya's Kongana community in the early 20th century.

- ^ Attested among Tevorangh-Taivoan communities, including Siaolin, Alikuan, and Kahsianpoo, in the early 20th century.

- ^ Attested mainly in Suannsamna.

- ^ Attested mainly in Dazhuang.

- ^ Attested in Makatao's Kanapo community in the early 20th century.

References

edit- ^ a b Ferrell, Raleigh (1971). "Aboriginal Peoples of the Southwestern Taiwan Plains". Bulletin of the Institute of Ethnology. 32: 217–235.

- ^ a b Li, Paul Jen-kuei (2009). "Linguistic Differences Among Siraya, Taivuan, and Makatau". In Adelaar, A; Pawley, A (eds.). Austronesian Historical Linguistics and Culture History: A Festschrift for Robert Blust. Pacific Linguistics 601. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. pp. 399–409. hdl:1885/34582. ISBN 9780858836013.

- ^ "639 Identifier Documentation: tvx". SIL International. 2019-01-25. Retrieved 2019-01-29.

- ^ De Dagregisters van het Kasteel Zeelandia, Taiwan: 1629–1662 (in Dutch). ʼS-Gravenhage: M. Nijhoff. 1986.

- ^ a b Lee, Jui-Yuan (2015). From Single to Group: The Formation of Sideia in the 17th Century. Department of History: National Cheng Kung University.

- ^ a b c d Tsuchida, Shigeru; Yamada, Yukihiro; Moriguchi, Tsunekazu (1991). Linguistic Materials of the Formosan Sinicized Populations I: Siraya and Basai. Tokyo: The University of Tokyo Department of Linguistics.

- ^ Blust, Robert; Trussel, Stephen (2018-05-12). "The Austronesian Comparative Dictionary, web edition". trussel2.com. Retrieved 2018-05-26.

- ^ Murakami, Naojirô (1933). "Sinkan Manuscripts", Memoirs of the Faculty of Literature and Politics, Taihoku Imperial University, Vol.2, No.1. Formosa: Taihoku Imperial University.

- ^ Campbell, William (1903). Formosa under the Dutch: Described from Contemporary Records. London: Kegan Paul. pp. 9. ISBN 978-957-638-083-9.

- ^ Li, Paul Jen-kuei (1996). "The Lingue Franche in Taiwan". In Wurm, Stephen A.; Mühlhäusler, Peter; Tryon, Darrell T. (eds.). Atlas of Languages of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

- ^ Alexander, Adelaar (2014). Phonology and Spelling System Reconstruction. Siraya languages study and revival seminars.

- ^ a b Adelaar, Alexander (2011). Siraya: Retrieving the Phonology, Grammar and Lexicon of a Dormant Formosan Language. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. p. 34. doi:10.1515/9783110252965. ISBN 978-3-11-025296-5.

- ^ a b Zhǒng huí Xiǎolín Cūn de jìyì: Dàwǔlǒng mínzú zhíwù jì bùluò chuánchéng 400 nián rénwén zhì 種回小林村的記憶 : 大武壠民族植物暨部落傳承400年人文誌 [A 400-Year Memory of Xiaolin Taivoan: Their Botany, Their History, and Their People] (in Chinese). Gaoxiong Shi: Gao xiong shi shan lin qu ri guang xiao lin she qu fa zhan xie hui. 2017. ISBN 978-986-95852-0-0.

- ^ Zhang, Zhenyue 張振岳 (2010). Dàzhuāng píngpǔ Xīlāyǎzú wénwù túshuō yǔ mínsú zhíwù tú zhì 大庄平埔西拉雅族文物圖說與民俗植物圖誌 [Illustrations of Cultural Relics and Ethnobotany of Pingpu Siraya in Dazhuang] (in Chinese). Hualian Shi: Hualian Xian wenhuaju. pp. 8–14. ISBN 978-986-02-5684-0.

- ^ "Gāoxióng Xiàn Dàwǔlǒng qún qiān xì---Kalawahe (jiālāwǎhēi) liù guī xīnglóng pān ānrán lǐngchàng/wángshùhuā dá chàng" 高雄縣大武壟群牽戲---Kalawahe(加拉瓦嘿) 六龜興隆潘安然領唱/王樹花答唱. YouTube (in Chinese). 2012-12-23. Retrieved 2018-05-30.

- ^ Taivoan Dance Theatre (2015), 歡喜來牽戲 (Let's Dance a Round Dance) (in Chinese), Kaohsiung: Taivoan Dance Theatre