The Camp on Blood Island is a 1958 British World War II film, directed by Val Guest for Hammer Film Productions and starring André Morell, Carl Möhner, Edward Underdown and Walter Fitzgerald.

| The Camp on Blood Island | |

|---|---|

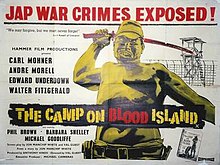

UK theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Val Guest |

| Written by | Jon Manchip White |

| Produced by | Anthony Hinds |

| Starring | André Morell Carl Möhner Edward Underdown Walter Fitzgerald Phil Brown Barbara Shelley Michael Goodliffe |

| Cinematography | Jack Asher |

| Edited by | Bill Lenny |

| Music by | Gerard Schurmann |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 82 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $3,500,000 (worldwide rentals)[1] |

The film is set in a Japanese prisoner of war camp in Japanese-occupied British Malaya and deals with the brutal, sadistic treatment of Allied prisoners of war by their captors. On its release, the film was promoted with the tag line "Jap War Crimes Exposed!", alongside a quote from Lord Russell of Liverpool, "We may forgive, but we must never forget", and an image of a Japanese soldier wielding a samurai sword.

From its powerful opening sequence of a man being forced to dig his own grave before being shot dead, an intertitle follows, stating "this is not just a story - it is based on brutal truth", The Camp on Blood Island is noted for a depiction of human cruelty and brutality which was unusually graphic for a film of its time. It received some contemporary allegations of going beyond the bounds of the acceptable and necessary into gratuitous sensationalism.

A prequel, The Secret of Blood Island, was released in 1964.

Plot

editEmperor Hirohito announces Japan's surrender to the Allies in a recorded radio address across the Empire on August 15, 1945, marking the end of the Pacific War. Crucially, this news has not reached the Japanese at the "Blood Island" prisoner-of-war camp, where commandant Colonel Yamamitsu, has told senior allied officer Colonel Lambert, he will order the massacre of the entire camp, including a nearby camp for women and children, if Japan surrenders. The news of the end of the war is known to Colonel Lambert, and former rubber planter Piet van Elst (or 'Dutch') from their secret radio receiver.

Colonel Lambert does not inform most of the other prisoners, but decides they must prevent the Japanese from learning the truth. He arranges to sabotage the Japanese radio and sends Dr. Robert Keiller to try to reach a Malay village, where partisans will be able to get a message to the Allies. These activities lead to savage reprisals by the Japanese, with threats of worse to come. Lambert is the commanding officer, so he is expected to give orders. However the other prisoners do not know of Yamamitsu's threat, or that the war is over.

Having been forced continually to justify his at times apparently illogical and counter-productive decisions, Lambert explains the situation to some senior prisoners, including former governor Cyril Beattie, whose wife and son are in interned in the women's camp, and priest Paul Anjou. Beattie thinks Lambert's approach is wrong, and that they should tell the Japanese. Anjou has been passing messages to the women via Mrs. Beattie, whilst delivering burial services in Latin, which the Japanese do not understand.

A U.S. Navy plane crashes onto the island and the pilot, Lt. Commander Peter Bellamy, flags down a Japanese truck, but is unable to communicate with the Japanese. A captured Dr. Keiller is lying in the truck and manages to tell Bellamy not to reveal that the war is over. The truck stops at the women's camp and Keiller is shot dead. The Japanese return to the men's camp, with Bellamy, and Keiller's body. Bellamy is questioned and beaten, but does not reveal the news.

Since Keiller's escape was unsuccessful, word has not reached the Malay resistance, so the Allies are still unaware of the situation on Blood Island. Lambert asks Anjou to pass a message via Mrs. Beattie for Mrs. Keiller to be under the water tower at the women's camp at midnight. Anjou tries, but the person he is burying turns out to be Mrs. Beattie, so he cannot convey the message.

Bellamy and Dutch escape from a working party, leading to the beheading of six hostages. They overpower a truck driver bringing dispatches and steal his vehicle. They try to rendezvous with Mrs. Keiller; but she is not under the water tower, as Anjou could not give her the message. Bellamy breaks into the camp, kills a Japanese officer who is with one of the female prisoners (who the women suspect is a collaborator), forcing her to take him to Mrs. Keiller. They escape but Dutch is killed holding off the guards. Bellamy and Mrs. Keiller eventually make it to the Malay village to alert the Allies.

Back at the camp, Lambert apprises the NCOs of the situation. Not knowing if the escapees have reached the Malay village or not, he tells the NCOs to instruct the men to arm themselves with small weapons. The next day the Japanese bring Dutch's body back and take another six prisoners for execution, including Major Dawes from the officers' hut. Beattie talks Sakamura into taking him to Yamamitsu, insisting that he has something vital to tell him, but triggers a grenade, killing Sakamura and Yamamitsu. The prisoners attack the guards and a bloody fight ensues. Lambert inadvertently kills Tom Shields, who has seized a Japanese machine gun in a tower. Lambert lobs a grenade into the tower, thinking the gun is manned by a Japanese soldier. Allied paratroopers are eventually dropped on the camp, and the fight is over. The women's camp was taken without a shot being fired, so whilst many of the men are dead, their actions have at least saved the surviving women and children.

Cast

edit- André Morell as Col. Lambert

- Carl Möhner as Piet van Elst

- Edward Underdown as Major Dawes

- Walter Fitzgerald as Cyril Beattie

- Phil Brown as Lt. Commander Peter Bellamy

- Barbara Shelley as Kate Keiller

- Michael Goodliffe as Father Paul Anjou

- Michael Gwynn as Tom Shields

- Ronald Radd as Colonel Yamamitsu, Camp commandant

- Marne Maitland as Captain Sakamura

- Richard Wordsworth as Dr. Robert Keiller

- Mary Merrall as Helen Beattie

- Wolfe Morris as Interpreter

- Michael Ripper as Japanese Driver

- Edwin Richfield as Sergeant-Major

- Geoffrey Bayldon as Foster

- Lee Montague as Japanese Officer

- Barry Lowe as Betts

- Max Butterfield as Hallam

- Jan Holden as Nurse

Production

editThe film was allegedly based on a true story which Hammer executive Anthony Nelson Keys heard from a friend who had been a prisoner of the Japanese.[2] Keys in turn told the story to colleague Michael Carreras who commissioned John Manchip White to write a script. Finance was provided as part of a co-production deal with Columbia Pictures and shooting began at Bray Film Studios on 14 July 1957.[3]

Reception

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2018) |

The film was very successful at the box office, being one of the twelve most popular British movies of the year, despite sometimes hostile reviews[3] and earned rentals of $3.5 million worldwide.[1][4]

Kinematograph Weekly listed it as being "in the money" at the British box office in 1958.[5]

The novelisation of the script sold over two million copies and has been described as "arguably the most successful piece of merchandise ever licensed by Hammer."[6]

The chairman of the Motion Pictures Producers' Association of Japan, Shiro Kido, who was also the president of Japanese film studio Shochiku, wrote to Columbia Pictures who were distributing the film worldwide to request that the film be banned in the United States as it hurt US-Japanese relationships stating that "It is most unfortunate that a certain country still maintains a hostile feeling toward Japan and cannot forget the nightmare of the Japanese army." and bemoaning the film's advertising.[7]

References

edit- ^ a b "Hammer: Five-a-Year for Columbia". Variety. 18 March 1959. p. 19. Retrieved 23 June 2019 – via Archive.org.

- ^ Fowler, Roy (1988). "Interview with Val Guest". British Entertainment History Project.

- ^ a b Marcus Hearn, "The Camp of Blood Island" Viewing Notes, Camp of Blood Island DVD, 2009

- ^ "Britain's Money Pacers 1958". Variety. 15 April 1959. p. 60.

- ^ Billings, Josh (18 December 1958). "Others in the Money". Kinematograph Weekly. p. 7.

- ^ Marcus Hearn, The Hammer Vault, Titan Books, 2011 p19

- ^ "British 'Camp on Blood Island' May Hurt Japanese in U.S. - Kido Fears". Variety. 4 November 1958. p. 11. Retrieved 7 July 2019 – via Archive.org.

External links

edit- The Camp on Blood Island at IMDb

- The Camp on Blood Island at BritMovie (archived)