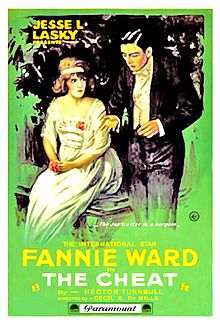

The Cheat is a 1915 American silent drama film directed by Cecil B. DeMille, starring Fannie Ward, Sessue Hayakawa, and Jack Dean, Ward's real-life husband.[2]

| The Cheat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Cecil B. DeMille (uncredited) |

| Written by | Hector Turnbull Jeanie MacPherson |

| Produced by | Cecil B. DeMille Jesse L. Lasky |

| Starring | Sessue Hayakawa Fannie Ward Jack Dean |

| Cinematography | Alvin Wyckoff |

| Edited by | Cecil B. DeMille |

| Music by | Robert Israel (1994) |

Production company | Jesse Lasky Feature Plays |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 59 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Languages | Silent English intertitles |

| Budget | $17,311[1] |

| Box office | $96,389 (domestic)[1] $40,975 (foreign)[1] |

Plot

editEdith Hardy is a spoiled society woman who continues to buy expensive clothes even when her husband, Richard, tells her all his money is sunk into a stock speculation and he can't pay her bills until the stock goes up. She even delays paying her maid her wages, and the embarrassed Richard must do so. Edith is also the treasurer of the local Red Cross fund drive for Belgian refugees, which holds a gala dance at the home of Hishuru Tori, a rich Japanese ivory merchant (or, in the 1918 re-release, Haka Arakau, a rich Burmese ivory merchant). He is an elegant and dangerously sexy man, to whom Edith seems somewhat drawn; he shows her his roomful of treasures, and stamps one of them with a heated brand to show that it belongs to him.

A society friend of the Hardys tells Edith that Richard's speculation will not be profitable and he knows a better one; he then offers to double her money in one day if she gives it to him to invest in the suggested enterprise. Edith, wanting to live lavishly and unwilling to wait for Richard to realize his speculation, takes the $10,000 the Red Cross has raised from her bedroom safe and gives it to the society friend.

The next day, however, her horrified friend tells her his tip was worthless and her money is completely lost. The Red Cross ladies have scheduled the handover of the money to the refugee fund for the day after that. Edith goes to Tori/Arakau to beg for a loan of the money, and he agrees to write her a check in return for her sexual favours the next day. She reluctantly agrees to this, takes his check and is able to give the money to the Red Cross. Then Richard announces elatedly that his investments have paid off and they are very rich. Edith asks him for $10,000, saying it is for a bridge debt, and he writes her a check for the amount with no reproof.

She takes it to Tori/Arakau, but he says she cannot buy her way out of their bargain. When she struggles against his advances, he takes his heated brand used to mark his possessions and brands her with it on the shoulder. In their struggle after that, she finds a gun on the floor and shoots him. She runs away just as Richard, hearing the struggle, bursts into the house. He finds the check he wrote to his wife there. Tori/Arakau is only wounded in the shoulder, not killed; when his servants call the police, Richard declares that he shot him, and Tori/Arakau does not dispute this.

Edith pleads with Tori/Arakau not to press charges, but he refuses to spare Richard. She visits Richard in his jail cell and confesses everything, and he orders her not to tell anyone else and let him take the blame. At the crowded trial, both he and Tori/Arakau, his arm in a sling, testify that he was the shooter but will not say why. The jury finds Richard guilty.

This is too much for Edith, and she rushes to the witness stand and shouts that she shot Tori/Arakau "and this is my defense". She bares her shoulder and shows everyone in the courtroom the brand on her shoulder. The male spectators are infuriated and rush to the front, clearly intending to lynch Tori/Arakau. The judge protects him and manages to hold them off. He then sets aside the verdict, and the prosecutor withdraws the charges. Richard lovingly and protectively leads the chastened Edith from the courtroom.

Cast

edit- Fannie Ward as Edith Hardy

- Sessue Hayakawa as Hishuru Tori (original release) / Haka Arakau (1918 re-release)

- Jack Dean as Richard Hardy

- James Neill as Jones

- Yutaka Abe as Tori's Valet

- Dana Ong as District Attorney

- Hazel Childers as Mrs. Reynolds

- Arthur H. Williams as Courtroom Judge (as Judge Arthur H. Williams)

- Raymond Hatton as Courtroom Spectator (uncredited)

- Dick La Reno as Courtroom Spectator (uncredited)

- Lucien Littlefield as Hardy's Secretary (uncredited)

Production and release

editThe Cheat featured art direction by Wilfred Buckland.[2]

Upon its release, The Cheat was both a critical and commercial success. The film's budget was $17,311. It grossed $96,389 domestically and $40,975 in the overseas market. According to Scott Eyman's Empire of Dreams: The Epic Life of Cecil B. DeMille, the film cost $16,540 to make, and grossed $137,364.[1]

Upon its release, the character of Hishuru Tori was described as a Japanese ivory merchant. Japanese Americans protested against the film for portraying a Japanese person as sinister. In particular, a Japanese newspaper in Los Angeles, Rafu Shimpo, waged a campaign against the film and heavily criticized Hayakawa's appearance. When the film was re-released in 1918, the character of Hishuru was renamed "Haka Arakau" and described in the title cards as a "Burmese ivory king". The change of the character's name and nationality were done because Japan was an American ally at the time. Robert Birchard, author of the book Cecil B. DeMille's Hollywood, surmised that the character's nationality was changed to Burmese because there were "not enough Burmese in the country to raise a credible protest."[3] Despite the changes, the film was banned in the United Kingdom and was never released in Japan.[4]

The film inspired French film critics to coin the term photogenie to specify cinema's medium-specific qualities and was filmed with innovative usage of lighting that helped raise awareness of film as a serious art form.

Critical reception

editMoving Picture World gave it a glowing review:

Space bids me be brief. I cannot, however, omit words of unqualified praise for Fanny Ward, whose impersonation of the social butterfly with the singed wings was a masterly performance. The lighting effects must be mentioned, too. They are beyond all praise in their art, their daring and their originality. There are those deft and subtle touches that we find all the Lasky pictures possess--only here they crowd upon one another. What a delicate but powerful effect was the omission of the bars in the prison scene. The shadow of the bars, the sombre light, the bent head of the prisoner silhouetted against the bare wall--this is but one of the numerous happy touches. The Cheat is worth advertising to the limit. It is one feature in a hundred.[5]

Accolades

editThe film was nominated for the American Film Institute's 2001 list AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills.[6] It was also nominated in the 2007 AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) list.

Remakes and adaptations

editThe film was remade in 1923, with George Fitzmaurice as director and Pola Negri and Jack Holt starring. In 1931, Paramount again remade The Cheat, with Broadway mogul George Abbott as director and starring Tallulah Bankhead.[4]

The Cheat was also remade in France as Forfaiture (1937) directed by Marcel L'Herbier. This version, however, makes significant changes to the original story, even though Hayakawa was cast once again as the sexually predatory Asian man.[3]

An operatic adaptation of the story, La Forfaiture, with music by Camille Erlanger and a libretto by André de Lorde and Paul Milliet, premiered at the Opéra-Comique in 1921. The first opera to be based on a film scenario, it was not a success, playing only three times.[7]

Preservation and availability

editIn 1993, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry.[4][8][9]

Copies of The Cheat are held by:

- George Eastman House on 35 mm movie film. This surviving version is the 1918 re-release footage which includes changes to the Hishuru Tori character.[10]

- Cinematheque Royale de Belgique

- Cineteca Del Friuli in Gemona on 16 mm film

- Library of Congress on 35 mm film and Laserdisc

- British Film Institute

- UCLA Film and Television Archive on 35 mm film and video

- Academy Film Archive on video

- Harvard Film Archive on 35 mm film[11]

The Cheat, which is now in public domain, was released on DVD in 2002 with another DeMille film Manslaughter (1922) by Kino International.[12][13]

References

edit- ^ a b c d Eyman, Scott (2010). Empire of Dreams: The Epic Life of Cecil B. DeMille. Simon and Schuster. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-439-18041-9.

- ^ a b "The Cheat". afi.com. Retrieved March 30, 2024.

- ^ a b Birchard, Robert (2004). Cecil B. DeMille's Hollywood. University Press of Kentucky. p. 70. ISBN 0-813-12324-0.

- ^ a b c Eagan, Daniel (2010). America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry. Continuum. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-826-42977-3.

- ^ Chalmers Publishing Company (1915). Moving Picture World (Dec 1915). New York The Museum of Modern Art Library. New York, Chalmers Publishing Company.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ Miyao, D. (2007). Sessue Hayakawa: Silent Cinema and Transnational Stardom. Duke University Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-8223-3969-4. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ "Librarian Announces National Film Registry Selections (March 7, 1994) - Library of Congress Information Bulletin". www.loc.gov. Retrieved September 18, 2020.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Retrieved September 18, 2020.

- ^ Birchard 2004 pp.69-70

- ^ "American Silent Feature Film Database: The Cheat". Library of Congress. Retrieved March 30, 2024.

- ^ "The Cheat". silentera.com.

- ^ "2002 Kino on Video DVD edition". silentera.com.

External links

edit- Media related to The Cheat (1915 film) at Wikimedia Commons

- The full text of The Cheat (1915 film) at Wikisource

- The Cheat at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- The Cheat at IMDb

- The Cheat at AllMovie

- The Cheat at the TCM Movie Database

- The Cheat is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive