The Plumber is a 1979 Australian psychological thriller film about a psychotic plumber who terrorizes a grad student. Written and directed by Peter Weir, The Plumber was originally made and broadcast as a television film in Australia in 1979 but was subsequently released to theatres in several countries beginning with the United States in 1981.[1] The film was made shortly after Weir's critically acclaimed Picnic at Hanging Rock became one of the first Australian films to appeal to an international audience.[2] The film stars Judy Morris, Ivar Kants, and Robert Coleby, all of them being most notable at the time as actors in Australian soap operas.[3]

| The Plumber | |

|---|---|

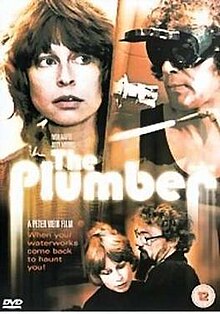

DVD cover | |

| Written by | Peter Weir |

| Directed by | Peter Weir |

| Starring | Judy Morris Ivar Kants |

| Music by | Rory O'Donoghue Gerry Tolland |

| Country of origin | Australia |

| Original language | English |

| Production | |

| Producer | Matt Carroll |

| Cinematography | David Sanderson |

| Editor | Gerald Turney-Smith |

| Running time | 76 minutes |

| Original release | |

| Release | 8 June 1979 |

Plot

editDr. Brian Cowper takes a shower in the flat he shares with his wife Jill, who is a masters student in anthropology. As he exits the building's lift on his way to work, an ominous character is seen entering and randomly choosing the button for the ninth floor. He knocks on the Cowpers' door and announces himself as Max, the building's plumber. Jill insists that they did not call for a plumber, and Max assures her that he is simply doing a mandatory check of the building's pipes.

Max maintains an affable, loquacious facade. Once inside the bathroom, he starts to chip away at the tile under the sink. When Jill rushes to the bathroom to see what he is doing, Max impishly encourages her to leave him to his work. He closes the door and then takes a very loud shower. Meanwhile, Brian has been informed that a team from the World Health Organization is coming to interview him about his work. He calls Jill to share the news, and in his glee, he dismisses her concerns about Max.

Max tells Jill that the apartment's pipes are a mess and that he will come back tomorrow to replace them. After he leaves, Jill goes to the bathroom to look at the mess that Max made, and he suddenly appears behind her. He claims that the door was unlocked and that he was just bringing in her groceries, since he had noticed they were in a heavy box. This basic pattern of Max's odd, slightly ominous behaviour recurs and expands throughout the film. He keeps finding excuses to visit the unit, and his work in the bathroom only makes a bigger mess each time. Because Brian never sees Max, he dismisses Jill's concerns out of hand. In one shot, Max patiently waits in his car for Brian to leave before heading up to the apartment.

Max eventually erects an elaborate scaffolding in the bathroom which renders it largely useless. As the Cowpers host the WHO officials for dinner, one of their guests gets himself trapped in the rigging and injures himself. During an argument with Jill, Max finally promises to finish his work, threatening that he will do a haphazard job just to get it over with. Sure enough, the plumbing explodes, pouring fetid water all over the bathroom, and prompting the return of Max to the apartment.

The police arrest Max, search his car and find items that belong to Jill that she placed there to frame him. She looks down on the arrest from her balcony, and Max screams at her that she set him up.

Cast and characters

edit- Judy Morris as Jill Cowper

- Ivar Kants as Max

- Robert Coleby as Brian Cowper

- Candy Raymond as Meg

- Henri Szeps as David Medavoy

Production

editThe film was one of three movies the South Australian Film Corporation had contracted to make for Channel Nine. It was shot on 16mm over three weeks.[4] In an interview, Weir said that the idea for the film came from a dinner conversation with a friend about a plumber who had "terrorized" her. As a television film project "made from one end to the other" and "was done very quickly and with no fuss," written "mostly because I needed the money, which is sometimes a good way of doing things."[5] Weir also revealed that during production he videotaped each cut so that he could review and screen them at home before the final version would be edited. "There’s a curious ritual about going into the cutting room and looking at what the editor has done the day or night before. This demystified that cutting-room".[6]

Reception

editJanet Maslin, reviewing the film for The New York Times, described the film as "more evidence of the versatility of Peter Weir" and as "a droll, claustrophobic work of absurdist humor." Drawing attention to Jill's role as an anthropology student, Maslin contends that "Mr. Weir's point here, as it has been in other films, is that the line dividing civilized behavior from more primitive kinds is so thin as to be nonexistent."[7]

Other critics have also drawn attention to the issues of class and gender that the film evokes. Comparing Weir's production to Michael Haneke's Funny Games, Felicia Feaster calls The Plumber "a skin-crawling examination of the quiet subterranean struggle for power that can unfold between two people."[8] Professor William "Bill" Blick puts even more emphasis on the class division between Max the plumber and Jill the anthropology student: "The Plumber seems to be escapist entertainment on the surface. Yet at the heart of this off-beat genre piece is a revelation of social conventions and classism."[9] Tim Brayton places the movie within the context of the simultaneous rise of Australian "art-house" movies, like Weir's The Last Wave, and "Ozploitation" (Australian exploitation) films like Weir's The Cars That Ate Paris and Peter Jackson's early movies, remarking, "Weir is a point where Ozploitation and the Australian New Wave meet up."[10]

On Rotten Tomatoes the film has 3 reviews listed, all positive.[11]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Maslin, Janet. Peter Weir's 'The Plumber', The New York Times, 1 December 1981. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- ^ Groenewegen, Stephen. The Plumber, eFilmCritic.com, 25 July 2003. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- ^ Tooze, Gary. The Plumber, DVDBeaver.com. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- ^ David Stratton, The Last New Wave: The Australian Film Revival, Angus & Robertson, 1980 p79-80

- ^ Matthews, Sue (1985). "Interview with Peter Weir, from 35 mm Dreams: Conversations with Five Directors about the Australian Film Revival". The Peter Weir Cave. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ Lindbergs, Kimberly (12 October 2017). "Untapped Fears: The Plumber (1979)". Cinebeats. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (1 December 1981). "Peter Weir's 'The Plumber'". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ Feaster, Felicia (7 July 2011). "The Plumber". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ Blick, William "Bill" (November 2017). "Stopping Up the Works: Weir's The Plumber and Social Class Conflict". Senses of Cinema. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ Brayton, Tim (25 May 2020). "The Plumber (1979)". Alternate Ending. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ "The Plumber". Rotten Tomatoes.

External links

edit- The Plumber at IMDb

- The Plumber at AllMovie

- The Plumber at the TCM Movie Database

- The Plumber at Australian Screen Online

- The Plumber at Oz Movies