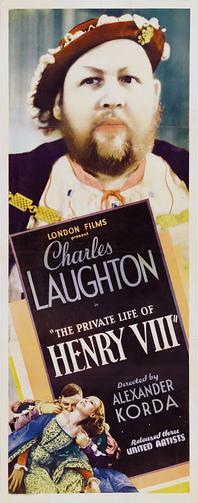

The Private Life of Henry VIII is a 1933 British film directed and co-produced by Alexander Korda and starring Charles Laughton, Robert Donat, Merle Oberon and Elsa Lanchester. It was written by Lajos Bíró and Arthur Wimperis for London Film Productions, Korda's production company. The film, which focuses on the marriages of King Henry VIII of England, was a major international success, establishing Korda as a leading filmmaker and Laughton as a box-office star.

| The Private Life of Henry VIII | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Alexander Korda |

| Written by | Lajos Bíró Arthur Wimperis |

| Produced by | Alexander Korda Ludovico Toeplitz |

| Starring | Charles Laughton Binnie Barnes Robert Donat |

| Cinematography | Georges Périnal |

| Edited by | Stephen Harrison |

| Music by | Kurt Schröder |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time | 97 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £93,710[1] |

| Box office | £750,000[2] |

Plot

editThe film begins 20 years into King Henry VIII's reign. In May 1536, in the immediate aftermath of the execution of his second wife Anne Boleyn, Henry married Jane Seymour, who died in childbirth 18 months later. He then weds a German princess, Anne of Cleves. This marriage ends in divorce after Anne deliberately makes herself unattractive so that she may be free to marry her sweetheart. Henry next marries the beautiful and ambitious Lady Katherine Howard. She has rejected love all of her life in favour of ambition, but after her marriage, she falls in love with Henry's handsome courtier Thomas Culpeper, who had attempted to woo her in the past. Their liaison is discovered by Henry's court and the two are executed. The weak and aging Henry consoles himself with a final marriage to Catherine Parr, who proves domineering. In the final scene, while Parr is no longer in the room, the king breaks the fourth wall, saying "Six wives, and the best of them's the worst."

Cast

edit- Charles Laughton as Henry VIII

- Merle Oberon as Anne Boleyn

- Wendy Barrie as Jane Seymour

- Elsa Lanchester as Anne of Cleves

- Binnie Barnes as Katherine Howard

- Everley Gregg as Catherine Parr

- Robert Donat as Thomas Culpeper

- Franklin Dyall as Thomas Cromwell

- Miles Mander as Wriothesley

- Laurence Hanray as Archbishop Thomas Cranmer

- William Austin as The Duke of Cleves

- John Loder as Thomas Peynell

- Lady Tree as The King's Nurse

- John Turnbull as Hans Holbein

- Frederick Culley as Duke of Norfolk

- William Heughan as Kingston

- Judy Kelly as Lady Rochford

- Hay Petrie as The King's Barber

- Wally Patch as Butcher

- Arthur Howard as Kitchen Helper

- Annie Esmond as Cook's Wife

- Claud Allister as Cornell

- Gibb McLaughlin as The French Executioner

- Sam Livesey as The English Executioner

Production

editAlexander Korda was seeking a film project suitable for Charles Laughton and his wife Elsa Lanchester. Originally, the story was to focus solely on the marriage of King Henry VIII and his fourth wife Anne of Cleves, but as the project grew, the story was modified to focus on five of Henry's six wives. Only the first wife, Catherine of Aragon, was omitted because those involved had no particular interest in her, describing her as a "respectable woman" in the film's first intertitles. Korda chose to ignore the religious and political aspects of Henry's reign, as the film makes no mention of the break with Rome and instead focuses on Henry's relations with his wives.[3]

The film cost £93,710 which was five times the average cost of a British feature in the early 1930s.[4]

Reception

editBox office

editThe Private Life of Henry VIII was a commercial success. It made Alexander Korda a premier figure in the film industry, and United Artists signed him for 16 films. It also advanced the careers of Charles Laughton, Robert Donat and Merle Oberon (in her first major film role). Laughton would later reprise the same role in the 1953 film Young Bess opposite Jean Simmons as his daughter Elizabeth.

The film earned receipts of £81,825 in the UK, which was not enough to recover its production costs.[5] However it was hugely successful overseas, being the 12th-most-successful of 1933 at the American box office[6] and ultimately earned rentals of £500,000 on its first release.[7]

It premiered to record-breaking crowds at New York's Radio City Music Hall and London's Leicester Square Theatre (now the Odeon West End), where it ran for nine weeks from 27 October 1933.[8]

Awards

editAt the Academy Awards, the film was the first foreign picture to win an Oscar (Charles Laughton for Best Actor), and the first foreign Best Picture nominee.

Laughton was voted best actor in a British film by readers of Film Weekly.[9]

Analysis

editHistorian Greg Walker has noted that Korda integrated references to contemporary political issues, as the film anachronistically refers to the Holy Roman Empire as Germany and portrays the empire as more united than it really was at the time.[10] The frequent wars between Holy Roman Emperor Charles V against King Francis I of France are depicted as examples of French–German enmity, with Henry attempting to act as peacemaker.[11] The film inaccurately portrays the French fighting Germans in the Habsburg-Valois wars rather than the Spanish.[10]

In the interwar period, the Treaty of Versailles was widely considered in Britain to be excessively harsh toward Germany, and successive British governments attempted to promote revision of the Versailles treaty in Germany's favour while also guarding against a resurgence of German militarism.[11] The Locarno Treaties of 1925 were an attempt to improve Franco-German relations, and evidence suggests that this policy was very popular with the British people.[12] Henry's monologue warning that the French and Germans will destroy Europe because of their mutual hatred and declaring that it is his duty to save the peace may have been understood by a 1933 British audience as an allegory for the current British policy of leniency toward Germany.[11]

The film possibly refers to the 1932 World Disarmament Conference and the current debate about rearmament when Henry is warned by Thomas Cromwell that spending on the navy will "cost us much money," to which he retorts that not to spend money on the navy will "cost us England."[13] Korda disliked the Labour Party's call for disarmament, and Henry's message in the film may have been a rebuke to those who called for Britain to continue with disarmament[14] and to those in the government who were cutting military spending in light of the Great Depression.[15]

In the 1920s and 1930s, many in Britain bristled at Hollywood's domination of the film industry;[16] by 1925, only 5% of the films shown in Britain were British.[17] In 1932, Sir Stephen Tallents called for "The Projection of England", warning that if the British film industry failed to tell its own stories that would define Britain, then Hollywood would do so.[18] This sparked interest in the Tudor era[18] and an image of the period as a prosperous, happy time untroubled by class divisions and economic depressions.[18] The character of John Bull was portrayed as uncultured but kind, boisterous and exuberant, all qualities perceived as typically British.[17] His lack of sophistication hid a mind that was shrewd and cunning, also a reflection of British self-image at the time.[17] Korda, a Hungarian immigrant who craved acceptance in Britain, may have ascribed much of John Bull's imagery and traits to Henry VIII in the film.[17]

Catherine of Aragon is excluded from the script because she was a "respectable woman," in the words of the introductory titles,[19] but the exclusion may have occurred because the real-life Catherine stubbornly refused to allow Henry to marry Anne Boleyn, a fact that might have weakened the audience's identification with the king. The film also does not mention that Boleyn was convicted of false charges of incest with her brother, who was also executed, a fact that might have pitted the audience against Henry.[20] The film inaccurately depicts Henry marrying Jane Seymour on the same day as Boleyn was beheaded; in fact, Henry only obtained permission to remarry that day, marrying Seymour on 30 May 1536.[21] The film's portrayal of Seymour as a vain, stupid, childlike woman contradicts some accounts that the real Seymour was an intelligent woman.[21]

Anne of Cleves is inaccurately shown in love with another man before she marries Henry, and this is presented as her reason for wanting to end the marriage. The relationship is played for comic effect, but the real process of ending the marriage lasted several weeks rather than over the course of a single night as portrayed in the film. Anne's desire to remain in England is attributed to her love for Peynell in the film, but in reality, her motivation may have been to escape the tyrannical supervision of her stern brother, the Duke of Cleves.[22]

According to historical accounts, Catherine Howard was an immature teenager of limited intelligence who did not realize the grave risk involved with her adultery.[23] However, the film portrays Howard as a mature, intelligent woman who knew the risks of adultery, an inaccuracy that may have been intended to elicit audience sympathy for Henry's decision to have her executed.[23]

Catherine Parr may also have been inaccurately portrayed; rather than a nagging tyrant, the real Parr was an intellectual with a strong interest in theology and a gentle demeanour who engaged Henry in intellectual discussions about religion in his final years.[24]

Legacy

editThe Private Life of Henry VIII is credited with creating the popular image of Henry VIII as a fat, lecherous glutton who eats turkey legs and tosses bones over his shoulder (although in the film, Henry eats an entire chicken).[25][26][27][28][29]

Historian Alison Weir has pointed out that this image is contradicted by primary sources, noting: "As a rule, Henry did not dine in the great halls of his palaces, and his table manners were highly refined, as was the code of etiquette followed at his court. He was in fact a most fastidious man, and—for his time—unusually obsessed with hygiene. As for his pursuit of the ladies, there is plenty of evidence, but most of it fragmentary, for Henry was also far more discreet and prudish than we have been led to believe. These are just superficial examples of how the truth about historical figures can become distorted."[30]

Copyright status

editThis section possibly contains original research. (February 2021) |

As a result of overlapping changes in British copyright law, the film never fell into the public domain in the UK and its copyright is now due to expire at the end of 2026, 70 years after Alexander Korda's death. In countries that observe a 50-year term, such as Canada and Australia, the copyright expired at the end of 2006.

In the United States, the film's original 1933 copyright registration[31] was not renewed after the initial 28-year term, and the film thus fell into the public domain there. As a foreign film still in copyright in its country of origin, its American copyright was automatically restored in 1996 with a term of 95 years from release, meaning that the copyright will expire at the end of 2028.

Bibliography

edit- Law, Jonathan (1997). Cassell Companion to Cinema. London: Market House Books Limited. ISBN 0-304-34938-0.

- Magill, Frank (1980). Magill's Survey of Cinema. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Salem Press, Inc. ISBN 0-89356-225-4.

- Korda, Michael (1980). Charmed Lives: The Fabulous World of the Korda Brothers. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 0-7139-1318-5.

- Walker, Greg (2003). The Private Life of Henry VIII: A British Film Guide. London: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 1860649092.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Chapman, J. (2022). The Money Behind the Screen: A History of British Film Finance, 1945-1985. Edinburgh University Press p 17. Variety gave the figure as US $550,000 see "Good Pix Can't Be Made Cheaply". Variety. 12 June 1934. p. 21.

- ^ "British Film Losses". The Barrier Miner. Broken Hill, New South Wales. 8 February 1936. p. 3. Retrieved 4 August 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Lipscomb, Suzannah. "Henry VIII: a King Caught on Camera". History Today. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ Chapman p 17

- ^ Chapman, p 17.

- ^ "Box Office Successes of 1933". The West Australian. Perth. 13 April 1934. p. 3. Retrieved 9 July 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ D. W. (25 November 1934). "TAKING A LOOK AT THE RECORD". The New York Times. ProQuest 101193306.

- ^ Popular Filmgoing in 1930s Britain: A Choice of Pleasures, Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 2000, pp. 77–78

- ^ "Best Film Performance Last Year". The Examiner. Launceston, Tasmania. 9 July 1937. p. 8. Retrieved 4 March 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b Walker, Greg (9 September 2001). "The Private Life of Henry VII". History Today. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ a b c Walker 2003, p. 54-55.

- ^ Walker 2003, p. 55.

- ^ Walker 2003, p. 57.

- ^ Walker 2003, p. 55-56.

- ^ Walker 2003, p. 56-57.

- ^ Walker 2003, p. 29-30.

- ^ a b c d Walker 2003, p. 31.

- ^ a b c Walker 2003, p. 30.

- ^ Walker 2003, p. 89.

- ^ Walker 2003, p. 90.

- ^ a b Walker 2003, p. 91.

- ^ Walker 2003, p. 93.

- ^ a b Walker 2003, p. 94.

- ^ Walker 2003, p. 95.

- ^ "Painting of Henry VIII Holding a Turkey Leg – Debunking Mandela Effects". debunkingmandelaeffects.com.

- ^ "The Private Life of Henry VIII". 30 August 2010.

- ^ Body in Medical Culture, The. SUNY Press. 16 April 2009. ISBN 9781438425962 – via Google Books.

- ^ Richards, Jeffrey (10 February 1984). The Age of the Dream Palace: Cinema and Society in 1930s Britain. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9781848851221 – via Google Books.

- ^ "The Private Life of Henry VIII". History Today.

- ^ Weir, Alison (18 April 2011). Henry VIII: King and Court. Random House. ISBN 9781446449233 – via Google Books.

- ^ US Copyright Catalogue of Copyright Entries, 1933, Volume 6, No. 8, page 361 – 3 November 1933, #7757.

External links

edit- The Private Life of Henry VIII at IMDb

- The Private Life of Henry VIII at the BFI's Screenonline

- The Private Life of Henry VIII at AllMovie

- The Private Life of Henry VIII at the TCM Movie Database

- The Private Life of Henry VIII at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- The Private Life of Henry VIII at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Private Life of Henry VIII review at Old Movies