A transient lunar phenomenon (TLP) or lunar transient phenomenon (LTP) is a short-lived change in light, color or appearance on the surface of the Moon. The term was created by Patrick Moore in his co-authorship of NASA Technical Report R-277 Chronological Catalog of Reported Lunar Events, published in 1968.[1]

Claims of short-lived lunar phenomena go back at least 1,000 years, with some having been observed independently by multiple witnesses or reputable scientists. Nevertheless, the majority of transient lunar phenomenon reports are irreproducible and do not possess adequate control experiments that could be used to distinguish among alternative hypotheses to explain their origins.

Most lunar scientists will acknowledge that transient events such as outgassing and impact cratering do occur over geologic time. The controversy lies in the frequency of such events.

Description of events

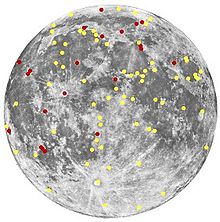

editReports of transient lunar phenomena range from foggy patches to permanent changes of the lunar landscape. Cameron[2] classifies these as (1) gaseous, involving mists and other forms of obscuration, (2) reddish colorations, (3) green, blue or violet colorations, (4) brightenings, and (5) darkening. Two extensive catalogs of transient lunar phenomena exist,[1][2] with the most recent tallying 2,254 events going back to the 6th century. Of the most reliable of these events, at least one-third come from the vicinity of the Aristarchus plateau.

An overview of the more famous historical accounts of transient phenomena include the following:

Pre 1700

edit- On June 18, 1178, five or more monks from Canterbury reported an upheaval on the Moon shortly after sunset:

This description appears outlandish, perhaps due to the writer's and viewers' lack of understanding of astronomical phenomena.[3][4] In 1976, Jack Hartung proposed that this described the formation of the Giordano Bruno crater. However, more recent studies suggest that it appears very unlikely the 1178 event was related to the formation of Crater Giordano Bruno, or was even a true transient lunar phenomenon at all. The millions of tons of lunar debris ejected from an impact large enough to leave a 22-km-wide crater would have resulted in an unprecedentedly intense, week-long meteor storm on Earth. No accounts of such a memorable storm have been found in any known historical records, including several astronomical archives from around the world.[5] In light of this, it is suspected that the group of monks (the event's only known witnesses) saw the atmospheric explosion of a directly oncoming meteor in chance alignment, from their specific vantage point, with the far more distant Moon.[6]There was a bright new moon, and as usual in that phase its horns were tilted toward the east; and suddenly the upper horn split in two. From the midpoint of this division a flaming torch sprang up, spewing out, over a considerable distance, fire, hot coals, and sparks. Meanwhile the body of the moon which was below writhed, as it were, in anxiety, and, to put it in the words of those who reported it to me and saw it with their own eyes, the moon throbbed like a wounded snake. Afterwards it resumed its proper state. This phenomenon was repeated a dozen times or more, the flame assuming various twisting shapes at random and then returning to normal. Then after these transformations the moon from horn to horn, that is along its whole length, took on a blackish appearance.

- On November 26, 1540, a transient phenomenon appeared between Mare Serenitatis and Mare Imbrium. This event is depicted on a contemporary woodcut.[7]

1701–1800

edit- On the evening of August 16, 1725, the Italian astronomer Francesco Bianchini saw a reddish light streak across the floor of crater Plato, "like a bar stretching straight from one end to the other" along the major axis of the foreshortened elliptical shape of the crater.[8]

- During the night of April 19, 1787, the British astronomer Sir William Herschel noticed three red glowing spots on the dark part of the Moon.[9] He informed King George III and other astronomers of his observations. Herschel attributed the phenomena to erupting volcanoes and perceived the luminosity of the brightest of the three as greater than the brightness of a comet that had been discovered on April 10. His observations were made while an aurora borealis (northern lights) rippled above Padua, Italy.[10] Aurora activity that far south from the Arctic Circle was very rare. Padua's display and Herschel's observations had happened a few days before the number of sunspots had peaked in May 1787.

- In December 1787, a luminous point was seen by a Maltese observer named d'Angos.[11]

- On September 26, 1789, the German astronomer Johann Hieronymus Schröter noticed a speck of light close to the eastern foot of the Montes Alpes. It was seen on the night side of the Moon and appeared like a star of Magnitude 5 to the naked eye.[12]

- On October 15, 1789, J.H.Schröter observed two bright bursts of light, each one of them composed of many single, separate small sparks, appearing on the night side of the Moon near crater Plato and Mare Imbrium.[13]

- In 1790, Sir William Herschel saw one or more star-like appearances on the eclipsed Moon.[11]

- On November 1–2, 1791, J.H.Schröter noticed the bowl-shaped crater Posidonius A on the floor of crater Posidonius without internal shadow.[14]

- In 1794, a report circulated that it was possible to see a volcano on the Moon with the naked eye.[11]

1801–1900

edit- Between 1830 and 1840, the German astronomer Johann Heinrich von Mädler observed a strong reddish tint closely east of crater Lichtenberg in Oceanus Procellarum.[15] See also Barcroft in 1940, Haas at a later date, Baum in 1951, and Hill in 1988.

- On November 24, 1865, Williams and two others observed for one hour and a half a distinct bright speck like an 8 magnitude star on the dark side near crater Carlini in Mare Imbrium.[16]

- In 1866, the experienced lunar observer and mapmaker J. F. Julius Schmidt claimed that the Linné crater had changed its appearance. Based on drawings made earlier by J. H. Schröter, as well as personal observations and drawings made between 1841 and 1843, he stated that the crater "at the time of oblique illumination cannot at all be seen"[17] (his emphasis), whereas at high illumination, it was visible as a bright spot. Based on repeat observations, he further stated that "Linné can never be seen under any illumination as a crater of the normal type" and that "a local change has taken place". Today, Linné is visible as a normal young impact crater with a diameter of about 1.5 miles (2.4 km).

- On January 4, 1873, French astronomer Étienne Léopold Trouvelot observed crater Kant which was "filled with mist".[18]

- On August 31, 1877, English amateur astronomer Arthur Stanley Williams noticed some sort of phosphorescent glow on the shadowed southern part of the walled plain Plato.[19]

- On August 6–7, 1881, German astronomer Hermann Joseph Klein observed the region of craters Aristarchus and Herodotus, and noticed a strong violet glare with some sort of nebulosity.[20]

- On March 27, 1882, A.S.Williams saw the floor of Plato at sunrise "glowing with a curious milky kind of light".[21]

- On July 3, 1882, several residents of Lebanon, Connecticut, observed two pyramidal luminous protuberances on the Moon's upper limb. They were not large, but gave the Moon a look strikingly like that of a horned owl or the head of an English bull terrier.[22]

- On February 19, 1885, Gray saw a small crater near the larger crater Hercules glow dull red "with vivid contrast".[23]

- On February 21, 1885, Knopp observed red patches in crater Cassini.[23]

- In 1887, French amateur astronomer and selenographer Casimir Marie Gaudibert noticed a temporary white spot in the central part of crater Herodotus.[24]

- One night in 1892, American astronomer Edward Emerson Barnard found the bowl of crater Thales filled with luminous haze.[25]

- 1891–1897, American astronomer William Henry Pickering gives drawings of a probable eruption of steam from crater Schröter.[26]

- A photograph made on August 26, 1898, through the équatorial coudé, shows bowl-shaped craterlet Posidonius C on the floor of crater Posidonius as a bright spot without shadow, although the terminator (day-night boundary) was nearby.[27]

1901–1950

edit- A photograph made on September 30, 1901, through the équatorial coudé, shows bowl-shaped craterlet Posidonius C as an elongated bright spot without shadow, although the photograph was made shortly before sunset at crater Posidonius.[27]

- In 1902, French astronomer Albert Charbonneaux, using the Meudon 33-inch refractor telescope at the Paris Observatory, noticed a small white cloud west of crater Theaetetus.[28]

- In 1905, German astronomer Friedrich Simon Archenhold observed a bright spot at the location of the bowl-shaped craterlet Posidonius C on the floor of crater Posidonius.[29]

- On May 19, 1912, Austrian astronomer and rocketry pioneer Max Valier noticed a small red glowing area on the Moon's night side.[23]

- In January 1913, William Henry Pickering observed the last one of a series of eruptions of some sort of white material at crater Eimmart.[30]

- On June 15, 1913, the British civil engineer and astronomer William Maw observed a 'small reddish spot' in crater South.[31]

- On February 22, 1931, Joulia observed a reddish glow in crater Aristarchus. In the same year (1931) and at the same location, British businessman and amateur astronomer Walter Goodacre and (?) Molesworth (1931?) observed a bluish 'glare'.[23] Percy B. Molesworth ? (1867–1908).

- On June 17, 1931, N.J.Giddings and his wife observed unusual flashes of light (lightning-like phenomena) on the night side of the Moon.[32]

- On August 2, 1939, British moon observer Patrick Moore noticed that the internal detail of the walled plain Schickard was obliterated by an extensive mist.[25]

- In 1940, American amateur astronomer David P. Barcroft (1897–1974) observed a pronounced reddish-brown color near crater Lichtenberg in Oceanus Procellarum.[15] See also J.H.Mädler between 1830 and 1840, Baum in 1951, and Hill in 1988.

- On July 10, 1941, American amateur astronomer Walter H. Haas noticed a moving dot of white light near crater Hansteen in the southern section of Oceanus Procellarum.[33]

- On August 31, 1944, the floor of the walled plain Schickard looked misty to the Welsh-born engineer and amateur astronomer Hugh Percy Wilkins. Some minor craters in it, which are normally well shadowed, stood out as white spots under a low sun.[25]

- On January 30, 1947, Harold Hill observed an abnormal absence of the main peak's shadow at the central mountain group of crater Eratosthenes.[34]

- On April 15, 1948, F.H.Thornton, using a 9-inch reflector, observed crater Plato and noticed a minute but brilliant flash of light which he described as looking very much like the flash of an AA shell exploding in the air at a distance of about ten miles. In color it was on the orange side of yellow.[35]

- On May 20, 1948, British amateur astronomer Richard M. Baum noted a reddish glow to the northeast of crater Philolaus, which he watched for fifteen minutes before it faded from sight. Three years later he observed another red glow west of crater Lichtenberg.[36]

- On February 10, 1949, F.H.Thornton, using an 18-inch reflector, observed the Cobra-Head of Vallis Schroteri and recorded a "puff of whitish vapour obscuring details for some miles in the area".[25]

- in November 1949, and also in June and July 1950, Bartlett noticed a white spot at the central part of crater Herodotus.[37]

1951–1960

edit- In 1951, Richard Myer Baum (1930–2017) observed the regions near crater Lichtenberg in Oceanus Procellarum and reported a rose-pink coloration which persisted for a time and then faded.[38] See also J.H.Mädler between 1830 and 1840, Barcroft in 1940, and Hill in 1988.

- On November 15, 1953, Dr. Leon Stuart photographed a lunar flare at approximately 10 miles southeast of crater Pallas. The duration of the flare was 8 to 10 seconds. According to Bonnie Buratti, the coordinates of the impacted object are 3.88° Latitude / 357.71° Longitude.

- On May 11, 1954, Peter Cattermole observed the disappearance of the central mountains of crater Eratosthenes, although the surrounding detail remained clearly visible.[25]

- In 1954, Patrick Moore detected curious ray-like features crossing crater Helmholtz.[39]

- On June 25, 1955, mountaineer and amateur astronomer Valdemar Axel Firsoff observed a faint mist in crater Theophilus.[25]

- On July 15, 1955, V.A.Firsoff observed crater Herodotus which had a 'pseudo central peak' casting a shadow.[40]

- On January 16–17, 1956, Robert Miles of Woodland, Calif., noticed a flash of white or bright blue light east of Mare Crisium.[41]

- On November 2, 1958, the Russian astronomer Nikolai A. Kozyrev observed an apparent half-hour "eruption" that took place on the central peak of Alphonsus crater using a 48-inch (122-cm) reflector telescope equipped with a spectrometer. During this time, the obtained spectra showed evidence for bright gaseous emission bands due to the molecules C2 and C3.[42] While exposing his second spectrogram, he noticed "a marked increase in the brightness of the central region and an unusual white colour." Then, "all of a sudden the brightness started to decrease" and the resulting spectrum was normal.

- On November 19, 1958, Raymond J. Stein of Newark observed a change in the shadow of crater Alpetragius.[43]

- On December 23, 1958, Greek observers of the moon noticed a greenish coloration at crater Schickard.[44]

1961–1970

edit- On October 29, 1963, two Aeronautical Chart and Information Center cartographers, James Clarke Greenacre and Edward M. Barr,[45] at the Lowell Observatory, Flagstaff, Arizona, manually recorded very bright red, orange, and pink colour phenomena on the southwest side of Cobra Head; a hill southeast of the lunar valley Vallis Schröteri; and the southwest interior rim of the Aristarchus crater.[46][47] This event sparked a major change in attitude towards TLP reports. According to Willy Ley: "The first reaction in professional circles was, naturally, surprise, and hard on the heels of the surprise there followed an apologetic attitude, the apologies being directed at a long-dead great astronomer, Sir William Herschel."[48] A notation by Winifred Sawtell Cameron states (1978, Event Serial No. 778): "This and their November observations started the modern interest and observing the Moon."[49] The credibility of their findings stemmed from Greenacre's exemplary reputation as an impeccable cartographer, rather than from any photographic evidence.

- On the night of November 1–2, 1963, a few days after Greenacre's event, at the Observatoire du Pic-du-Midi in the French Pyrenees, Zdeněk Kopal[50] and Thomas Rackham[51] made the first photographs of a "wide area lunar luminescence".[52] His article in Scientific American transformed it into one of the most widely publicized TLP events.[53] Kopal, like others, had argued that Solar Energetic Particles could be the cause of such a phenomenon.[54]

- On July 16, 1964, AAVSO member Thomas A. Cragg (1927–2011) observed a 3 km diameter "temporary hill casting a shadow" southeast of crater Ross D in Mare Tranquillitatis.[25]

- On November 15, 1965, personnel of the Trident Engineering Associates, Inc., Annapolis, Md. observed via Moon-Blink device a color phenomenon which lasted at least four hours.[55]

- On April 30 and May 1, 1966, Peter Sartory, Patrick Moore, P.Ringsdore, T.J.C.A.Moseley, and P.G.Corvan observed a wedge-shaped reddish colored appearance on the eastern part of crater Gassendi's floor.[56]

- In 1967, T.J.C.A.Moseley of the Armagh Observatory recorded a flash in the area of crater Parrot.[57]

- In 1968, J.C.McConnell reported that the north-east wall of crater Posidonius seemed hazy and obscured; the rest of the crater was clearly visible.[57]

- On April 13, 1968, during the eclipse of the Moon, Winifred Cameron of the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center noticed a great many star-like points on the Moon. They were seen by a group of observers who accompanied her.[57]

- K.E.Chilton: "At times, light is polarized in areas on the moon. On the night of September 18, 1968, I was observing the crater Gauss through a polaroid filter to cut down the glare. The eastern wall of the crater was not visible; when the filter was rotated the wall appeared, indicating that the area was reflecting polarized light. Although the same area has been examined since, this phenomenon has not been noticed again".[57]

- On October 31, 1968, K.E.Chilton observed a red-colored glow in crater Eratosthenes. The glow lasted 5 or 6 minutes and then faded to obscurity.[57]

- During the Apollo 11 mission in July 1969, Houston radioed to Apollo 11: "We've got an observation you can make if you have some time up there. There's been some lunar transient events reported in the vicinity of Aristarchus." Astronomers in Bochum, West Germany, had observed a bright glow on the lunar surface—the same sort of eerie luminescence that has intrigued Moon watchers for centuries. The report was passed on to Houston and thence to the astronauts. Neil Armstrong reported back: "Hey, Houston. I'm looking north up toward Aristarchus now, and I can't really tell at that distance whether I really am looking at Aristarchus, but there's an area there that is considerably more illuminated than the surrounding area. It just has – seems to have a slight amount of fluorescence to it as a crater can be seen, and the area around the crater is quite bright."[58]

1971–1980

edit- During the Apollo 17 mission in December 1972, Lunar Module Pilot Harrison Schmitt observed a bright flash-like phenomenon north of crater Grimaldi while in orbit around the Moon (First Revolution, 21:11:09 GMT, December 10, 1972).[59]

- While in orbit, Command Module Pilot Ronald Evans of Apollo 17 noticed a light flash eastward of Mare Orientale (14th Revolution, 22:28:27 GMT, December 11, 1972).[59]

- In September 1973, the Dutch author of books on mysterious phenomena Hans van Kampen and a friend (Van Cleef) observed near crater Linné a bright point of light which was visible for almost two minutes.[60]

1981–1990

edit- On December 27, 1982, British Moon observer Harold Hill noticed the absence of the principal craterlet (Nasmyth A) on the floor of the crater Nasmyth. A similar phenomenon was noticed by P.Wade on December 8, 1981.[61]

- On January 1, 1983, Harold Hill noticed an unusual bright appearance of craterlet Furnerius A near the pronounced crater Furnerius at the evening terminator.[62]

- On January 29, 1983, several members of the British Astronomical Association (BAA) observed abnormal brightness and purplish coloration at the bowl shaped crater Torricelli B north-northeast of the pear shaped crater Torricelli in Sinus Asperitatis.[63]

- On October 29, 1983, Harold Hill observed abnormal brightness at the hillock just north of crater Kirch.[64]

- On December 28, 1985, Harold Hill observed an extraordinary brilliance at the mid-section of the east inner wall of crater Peirescius.[62]

- On April 1, 1988, Harold Hill noticed rosy-tinged areas fringing the northern edge of the lava sheet near crater Lichtenberg in Oceanus Procellarum.[15] See also J.H.Mädler between 1830 and 1840, Barcroft in 1940, and Baum in 1951.

1991–2000

edit- In 1992, Audouin Dollfus of the Observatoire de Paris reported anomalous features on the floor of Langrenus crater using a one-meter (3.2-foot) telescope. While observations on the night of December 29, 1992, were normal, unusually high albedo and polarization features were recorded the following night that did not change in appearance over the six minutes of data collection.[65] Observations three days later showed a similar, but smaller, anomaly in the same vicinity. While the viewing conditions for this region were close to specular, it was argued that the amplitude of the observations were not consistent with a specular reflection of sunlight. The favored hypothesis was that this was the consequence of light scattering from clouds of airborne particles resulting from a release of gas. The fractured floor of this crater was cited as a possible source of the gas.[66]

No date given

edit- Johann Hieronymus Schröter once saw for a short time on the dark side, near craters Agrippa and Godin, a minute point of light.[67]

- J.Adams (English Mechanic N°2374) noted on two occasions near sunrise, when the interior of the walled plain Plato was filled with shadow, that two beams of light traversed two-thirds of the floor from the western wall resembling searchlights; they were parallel and well-defined, and had the appearance of passing through a slight vapour resting on the surface.[68]

- Harold Hill: "A number of observers have claimed in the past that the inner slopes of the formation Young have a greenish, almost translucent cast or sheen when seen at the evening terminator."[69]

- Patrick Moore: "There is a darkish streak across the floor of crater Fracastorius which is of a slightly reddish hue, and is detectable with a moonblink device."[18]

- American amateur astronomer David Barcroft (1897–1974) had seen the crater Timocharis "filled with vapor and very indistinct near full moon".[70]

- Spanish astronomer Josep Comas i Solà once saw crater Reiner "as a white patch when it should have been sharply defined".[70]

- T. W. Webb recommended crater Cichus (in the eastern part of Palus Epidemiarum) for further detailed study. In Cichus, a small crater seemed to have grown larger as compared to the earlier representations by Schröter and Mädler.[71]

Explanations

editExplanations for the transient lunar phenomena fall in four classes: outgassing, impact events, electrostatic phenomena, and unfavorable observation conditions.

Outgassing

editSome TLPs may be caused by gas escaping from underground cavities. These gaseous events are purported to display a distinctive reddish hue, while others have appeared as white clouds or an indistinct haze. The majority of TLPs appear to be associated with floor-fractured craters, the edges of lunar maria, or in other locations linked by geologists with volcanic activity. However, these are some of the most common targets when viewing the Moon, and this correlation could be an observational bias.

In support of the outgassing hypothesis, data from the Lunar Prospector alpha particle spectrometer indicate the recent outgassing of radon to the surface.[72] In particular, results show that radon gas was emanating from the vicinity of the craters Aristarchus and Kepler during the time of this two-year mission. These observations could be explained by the slow and visually imperceptible diffusion of gas to the surface, or by discrete explosive events. In support of explosive outgassing, it has been suggested that a roughly 3 km (1.9 mi) diameter region of the lunar surface was "recently" modified by a gas release event.[73][74] The age of this feature is believed to be about 1 million years old, suggesting that such large phenomena occur only infrequently.

Impact events

editImpact events are continually occurring on the lunar surface. The most common events are those associated with micrometeorites, as might be encountered during meteor showers. Impact flashes from such events have been detected from multiple and simultaneous Earth-based observations.[75][76][77][78] Tables of impacts recorded by video cameras exist for years since 2005 many of which are associated with meteor showers.[79] Furthermore, impact clouds were detected following the crash of ESA's SMART-1 spacecraft,[80] India's Moon Impact Probe and NASA's LCROSS. Impact events leave a visible scar on the surface, and these could be detected by analyzing before and after photos of sufficiently high resolution. No impact craters formed between the Clementine (global resolution 100 metre, selected areas 7–20 metre) and SMART-1 (resolution 50 metre) missions have been identified.[citation needed]

Electrostatic phenomena

editIt has been suggested that effects related to either electrostatic charging or discharging might be able to account for some of the transient lunar phenomena. One possibility is that electrodynamic effects related to the fracturing of near-surface materials could charge any gases that might be present, such as implanted solar wind or radiogenic daughter products.[81] If this were to occur at the surface, the subsequent discharge from this gas might be able to give rise to phenomena visible from Earth. Alternatively, it has been proposed that the triboelectric charging of particles within a gas-borne dust cloud could give rise to electrostatic discharges visible from Earth.[82] Finally, electrostatic levitation of dust near the terminator could potentially give rise to some form of phenomenon visible from Earth.[83]

Unfavourable observation conditions

editIt is possible that many transient phenomena might not be associated with the Moon itself but could be a result of unfavourable observing conditions or phenomena associated with the Earth. For instance, some reported transient phenomena are for objects near the resolution of the employed telescopes. The Earth's atmosphere can give rise to significant temporal distortions that could be confused with actual lunar phenomena (an effect known as astronomical seeing). Other non-lunar explanations include the viewing of Earth-orbiting satellites and meteors or observational error.[77]

Debated status of TLPs

editThe most significant problem that faces reports of transient lunar phenomena is that the vast majority of these were made either by a single observer or at a single location on Earth (or both). The multitude of reports for transient phenomena occurring at the same place on the Moon could be used as evidence supporting their existence. However, in the absence of eyewitness reports from multiple observers at multiple locations on Earth for the same event, these must be regarded with caution. As discussed above, an equally plausible hypothesis for some of these events is that they are caused by the terrestrial atmosphere. If an event were to be observed at two different places on Earth at the same time, this could be used as evidence against an atmospheric origin.

One attempt to overcome the above problems with transient phenomena reports was made during the Clementine mission by a network of amateur astronomers. Several events were reported, of which four of these were photographed both beforehand and afterward by the spacecraft. However, careful analysis of these images shows no discernible differences at these sites.[84] This does not necessarily imply that these reports were a result of observational error, as it is possible that outgassing events on the lunar surface might not leave a visible marker, but neither is it encouraging for the hypothesis that these were authentic lunar phenomena.

Observations are currently being coordinated by the Association of Lunar and Planetary Observers and the British Astronomical Association to re-observe sites where transient lunar phenomena were reported in the past. By documenting the appearance of these features under the same illumination and libration conditions, it is possible to judge whether some reports were simply due to a misinterpretation of what the observer regarded as an abnormality. Furthermore, with digital images, it is possible to simulate atmospheric spectral dispersion, astronomical seeing blur and light scattering by our atmosphere to determine if these phenomena could explain some of the original TLP reports.

Literature

edit- William R. Corliss: Mysterious Universe, A Handbook of Astronomical Anomalies (The Sourcebook Project, 1979).

- William R. Corliss: The Moon and the Planets, A Catalog of Astronomical Anomalies (The Sourcebook Project, 1985).

- Thomas William Webb: Celestial Objects for Common Telescopes, Volume 1: The Solar System (Dover Publications, 1962).

- Valdemar Axel Firsoff: The Old Moon and the New (Sidgwick & Jackson – London, 1969).

- A.J.M.Wanders: Op Ontdekking in het Maanland (Het Spectrum, 1949).

- Harry de Meyer: Maanmonografieën (Vereniging Voor Sterrenkunde, VVS, 1969).

- Patrick Moore: New Guide to the Moon (W.W.Norton & Company, 1976).

- Harold Hill: A Portfolio of Lunar Drawings (Cambridge University Press, 1991).

- Don E. Wilhelms: To a Rocky Moon, a Geologist's History of Lunar Exploration (The University of Arizona Press, 1993).

- William P. Sheehan & Thomas A. Dobbins: Epic Moon, A History of Lunar Exploration in the Age of the Telescope (Willmann Bell, 2001).

See also

edit- Geology of the Moon

- Lunar lava tube

- Lunar soil (see: Moon dust fountains and electrostatic levitation)

- Lunar swirls

- Observing the Moon

- Project A119

- Project Moon-Blink, a 1960s NASA investigation into transient lunar phenomena

- Selenography

- Splitting of the Moon

References

editCited references

- ^ a b Barbara M. Middlehurst; Burley, Jaylee M.; Moore, Patrick; Welther, Barbara L. (1967). "Chronological Catalog of Reported Lunar Events" (PDF). Astrosurf. NASA. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ^ a b Winifred S. Cameron. "Analyses of Lunar Transient Phenomena (LTP) Observations from 557–1994 A.D."

- ^ Jack B. Hartung (1976). "Was the Formation of a 20-km Diameter Impact Crater on the Moon Observed on June 18, 1178?". Meteoritics. 11 (3): 187–194. Bibcode:1976Metic..11..187H. doi:10.1111/j.1945-5100.1976.tb00319.x.

- ^ "The Giordano Bruno Crater". BBC.

- ^ Kettlewell, Jo (1 May 2001). "Historic lunar impact questioned". BBC. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ^ "The Mysterious Case of Crater Giordano Bruno". NASA. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ^ Barbara M. Middlehurst, An Analysis of Lunar Events, Reviews of Geophysics, May 1967, Vol.5, N°2, page 173

- ^ Bianchini, Observations concerning the planet Venus, translated by Sally Beaumont, Springer, 1996, p. 23, from Bianchini, Hesperi et phosphori nova phaenomena, Rome, 1728, pp. 5–6

- ^ Herschel, W. (1956, May). Herschel’s ‘Lunar volcanos.’ Sky and Telescope, pp. 302–304. (Reprint of An Account of Three Volcanos in the Moon, William Herschel’s report to the Royal Society on April 26, 1787, reprinted from his Collected Works (1912))

- ^ Kopal, Z. (December 1966). "Lunar flares". Astronomical Society of the Pacific Leaflets. 9: 401–408.

- ^ a b c K.E.Chilton, Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, Vol.63, page 203

- ^ T.W.Webb, Celestial Objects for Common Telescopes, Volume 1: The Solar System, page 113

- ^ K.Bispham, Schröter and Lunar Transient Phenomena, Journal of the British Astronomical Association, 78:381, 1968

- ^ A.J.M.Wanders, Op Ontdekking in het Maanland, blz 352

- ^ a b c Harold Hill, A Portfolio of Lunar Drawings, page 94

- ^ T.W.Webb: Celestial Objects for Common Telescopes, Volume 1: The Solar System, page 125 (lunar crater N°128: Carlini).

- ^ J. F. Julius Schmidt (1867). "The Lunar Crater Linne". Astronomical Register. 5: 109–110. Bibcode:1867AReg....5..109S.

- ^ a b Patrick Moore: New Guide to the Moon, page 289

- ^ A.J.M.Wanders, Op Ontdekking in het Maanland, blz 356

- ^ A.J.M.Wanders, Op Ontdekking in het Maanland, blz 159

- ^ A.J.M.Wanders, Op Ontdekking in het Maanland, blz 356. V.A.Firsoff, The Old Moon and the New, page 183

- ^ "A Curious Appearance of the Moon", Scientific American, 46:49, 1882

- ^ a b c d V.A.Firsoff, The Old Moon and the New, page 185

- ^ Harry De Meyer, Maanmonografieën P.72, Vereniging Voor Sterrenkunde (VVS), 1969

- ^ a b c d e f g V.A.Firsoff, The Old Moon and the New, page 183

- ^ T.W.Webb, Celestial Objects for Common Telescopes, Volume 1: The Solar System, page 161

- ^ a b A.J.M.Wanders, Op Ontdekking in het Maanland, blz 354

- ^ Patrick Moore, New Guide to the Moon, page 203

- ^ A.J.M.Wanders, Op Ontdekking in het Maanland, blz 353

- ^ "Change in a Lunar Crater", American Journal of Science, 4:38:95, 1914

- ^ V.A.Firsoff, The Old Moon and the New, page 185. T.W.Webb, Celestial Objects for Common Telescopes, Volume 1: The Solar System, page 163

- ^ N.J.Giddings, "Lightning-like phenomena on the Moon", Science, 104:146, 1946

- ^ Harry de Meyer, Maanmonografieën, blz 67, Vereniging Voor Sterrenkunde (VVS), 1969

- ^ Harold Hill, A Portfolio of Lunar Drawings, page 48

- ^ Patrick Moore, New Guide to the Moon, page 201

- ^ William P. Sheehan, Thomas A. Dobbins: Epic Moon, a history of lunar exploration in the age of the telescope, page 309

- ^ Harry De Meyer, Maanmonografieën P.72, Vereniging Voor Sterrenkunde (VVS), 1969

- ^ Harold Hill, A Portfolio of Lunar Drawings, page 94

- ^ Patrick Moore, New Guide to the Moon, page 292

- ^ V.A.Firsoff, The Old Moon and the New, page 182

- ^ Another Flashing Lunar Mountain? Strolling Astronomer, 10:20, 1956

- ^ Dinsmore Alter, Dinsmore (1959). "The Kozyrev Observations of Alphonsus". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 71 (418): 46–47. Bibcode:1959PASP...71...46A. doi:10.1086/127330.

- ^ Sky and Telescope, February 1959, page 211

- ^ Sky and Telescope, June 1961, page 337

- ^ Greenacre, J. A. (December 1963). "A recent observation of lunar colour phenomena". Sky & Telescope. 26 (6): 316–317. Bibcode:1963S&T....26..316G.

- ^ Zahner, D. D. (1963–64, December–January). Air force reports lunar changes. Review of Popular Astronomy, 57(525), 29, 36.

- ^ O'Connell, Robert; Cook, Anthony (August 2013). "Revisiting The 1963 Aristarchus Events". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 123 (4): 197–208. Bibcode:2013JBAA..123..197O.

- ^ Ley, W. (1965). Ranger to the moon (p. 71). New York: The New American Library of World Literature, Inc.

- ^ Cameron, W. S. (1978, July). Lunar transient phenomena catalog (NSSDC/WDC-A-R&S 78-03). Greenbelt, MD: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

- ^ Meaburn, J. (June 1994). "Z. Kopal". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society. 35 (2): 229–230. Bibcode:1994QJRAS..35..229M.

- ^ Moore, P. (2001). "Thomas Rackham, 1919–2001". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 111 (5): 291. Bibcode:2001JBAA..111..291M.

- ^ Kopal, Z.; Rackham, T. W. (1963). "Excitation of lunar luminescence by solar activity". Icarus. 2: 481–500. Bibcode:1963Icar....2..481K. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(63)90075-7.

- ^ Kopal, Z. (May 1965). "The luminescence of the moon". Scientific American. 212 (5): 28. Bibcode:1965SciAm.212e..28K. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0565-28.

- ^ Kopal, Z.; Rackham, T. W. (March 1964). "Lunar luminescence and solar flares". Sky & Telescope. 27 (3): 140–141. Bibcode:1964S&T....27..140K.

- ^ Project Moon-Blink – Final Report, Washington – NASA, October 1966

- ^ Patrick Moore, Color Events on the Moon, Sky and Telescope, 33:27, 1967

- ^ a b c d e K.E.Chilton, Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, Vol.63, page 203

- ^ "Apollo 11 Flight Journal – Day 4 part 3: TV from Orbit". Apollo Flight Journal. NASA. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ a b NASA SP-330, Apollo 17 Preliminary Science Report, P.28–29

- ^ Hans van Kampen, 40 jaar UFO's: de feiten – de meningen (De Kern, Baarn, 1987), blz 139

- ^ Harold Hill, A Portfolio of Lunar Drawings, pages 160–161

- ^ a b Harold Hill, A Portfolio of Lunar Drawings, page 232

- ^ Marie C. Cook, "The strange behaviour of Torricelli B", Journal of the British Astronomical Association, 110, 3, 2000

- ^ Harold Hill, A Portfolio of Lunar Drawings, page 60

- ^ Audouin Dollfus, A (2000). "Langrenus: Transient Illuminations on the Moon". Icarus. 146 (2): 430–443. Bibcode:2000Icar..146..430D. doi:10.1006/icar.2000.6395.

- ^ Dollfus, Audouin (March 11, 1999). "Langrenus: Transient Illuminations on the Moon" (PDF). Observatoire de Paris Report. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 22, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ T.W.Webb, Celestial Objects for Common Telescopes, Volume 1: The Solar System, page 118

- ^ T.W.Webb, Celestial Objects for Common Telescopes, Volume 1: The Solar System, page 162

- ^ Harold Hill, A Portfolio of Lunar Drawings, page 234

- ^ a b William P. Sheehan, Thomas A. Dobbins: Epic Moon, a history of lunar exploration in the age of the telescope, page 309

- ^ William P. Sheehan, Thomas A. Dobbins: Epic Moon, a history of lunar exploration in the age of the telescope, page 142

- ^ S. Lawson, Stefanie L.; W. Feldman; D. Lawrence; K. Moore; R. Elphic & R. Belian (2005). "Recent outgassing from the lunar surface: the Lunar Prospector alpha particle spectrometer". J. Geophys. Res. 110 (E9): E09009. Bibcode:2005JGRE..110.9009L. doi:10.1029/2005JE002433.

- ^ G. Jeffrey Taylor (2006). "Recent Gas Escape from the Moon". Planetary Science Research Discoveries.

- ^ P. H., Schultz; Staid, M. I. & Pieters, C. M. (2006). "Lunar activity from recent gas release". Nature. 444 (7116): 184–186. Bibcode:2006Natur.444..184S. doi:10.1038/nature05303. PMID 17093445. S2CID 7679109.

- ^ Tony Phillips (November 30, 2001). "Explosions on the Moon". Archived from the original on February 23, 2010.

- ^ Cudnik, Brian M.; Palmer, David W.; Palmer, David M.; Cook, Anthony; Venable, Roger; Gural, Peter S. (2003). "The Observation and Characterization of Lunar Meteoroid Impact Phenomena". Earth, Moon, and Planets. 93 (2): 97–106. Bibcode:2003EM&P...93...97C. doi:10.1023/B:MOON.0000034498.32831.3c. S2CID 56434645.

- ^ a b "Lunar impact monitoring". NASA. 6 March 2017. Archived from the original on 4 September 2019. Retrieved 31 October 2007.

- ^ "Bright Explosion on the Moon". NASA. May 17, 2013.

- ^ "2005-06 Impact Candidates". rates and sizes of large meteoroids striking the lunar surface. Marshall Space Flight Center. 5 September 2008. Archived from the original on 2016-06-25. Retrieved 2009-12-25.

- ^ "SMART-1 impact flash and dust cloud seen by the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope". 2006.

- ^ Richard Zito, R (1989). "A new mechanism for lunar transient phenomena". Icarus. 82 (2): 419–422. Bibcode:1989Icar...82..419Z. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(89)90048-1.

- ^ David Hughes, David W. (1980). "Transient lunar phenomena". Nature. 285 (5765): 438. Bibcode:1980Natur.285..438H. doi:10.1038/285438a0. S2CID 4319685.

- ^ Trudy Bell & Tony Phillips (December 7, 2005). "New Research into Mysterious Moon Storms". Space.com.

- ^ B. Buratti, B; W. McConnochie; S. Calkins & J. Hillier (2000). "Lunar transient phenomena: What do the Clementine images reveal?" (PDF). Icarus. 146 (1): 98–117. Bibcode:2000Icar..146...98B. doi:10.1006/icar.2000.6373.

General references

- William Sheehan & Thomas Dobbins (2001). Epic Moon: A History of Lunar Exploration in the Age of the Telescope. Willmann-Bell. pp. 363. ISBN 0-943396-70-0.

- Patrick Moore, On the Moon, Cassel & Co., 2001, ISBN 0-304-35469-4.

External links

edit- Lunar Transient Phenomena NASA feature story

- Lunar transient phenomena Association of Lunar & Planetary Observers

- NASA – Lunar Impact Monitoring Program Archived 2013-05-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Poratta, David (June 27, 2007). "Columbia Astronomer Offers New Theory Into 400-year-old Lunar Mystery". Columbia University. Retrieved 2007-06-28.

Professor Hakan Kayal of the Space Technology at Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg (JMU) in Bavaria, Germany – Moon telescope set up in Spain, to investigate Transient Lunar Phenomena