User:BushelCandle/sandbox/National identity cards in the European Economic Area

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2012) |

National identity cards are available for issue to all their citizens above a certain age from the governments of all European Economic Area (EEA) member states except Denmark, Ireland[1] Norway and the United Kingdom. (Gibraltar residents can be issued a biometric identity card and Norway has decided to start issuing such cards from 2017).

These national identity cards have considerable domestic utility in the surveillance of criminals and detection and prevention of crimes such as identity fraud, and under age drinking. For adults who do not have a driving licence they are particularly useful since other definitive state-issued identity documentation such as passports are usually both cumbersome to carry and considerably more expensive. EEA ID cards are often accepted in other parts of the world for similar unofficial identification purposes and sometimes also for official purposes such as proof of identity and nationality.

Although Switzerland is not formally part of the EEA, citizens holding an EEA or Swiss national identity card that states they have EEA or Swiss citizenship, can not only use it as an identity document within their home country, but also as a travel document to exercise the right of free movement in the EEA and Switzerland.[2] Identity cards that do not state EEA or Swiss citizenship, including national identity cards issued to residents who are not citizens, are not valid as a travel document within the EEA and Switzerland[citation needed].

History

editPerhaps the earliest "identity cards" in what is now an EEA territory, would have been the terracotta tiles carried by Roman ex-slaves to certify their emancipation.[3]

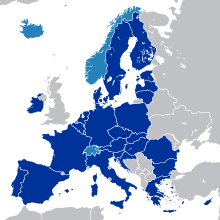

Dark blue: French Empire

Light blue: French satellite states

and occupied zones

Blue-grey: Countries forced by France

into the Continental System.

However, the French identity card re-introduced by Napoleon in 1803 might be considered as the main ancestor of many of the modern, government issued, identity cards in Europe today.[4] Napoleon transformed the French Republic into the Empire, a tightly controlled police state. His new identity card, based on the old livret d'ouvrier but updated with new identity features, had a purpose in holding down wages, by providing an additional obstacle to workers moving around to find better jobs and better remuneration.[5] The necessity for workers to get an impossible string of visas before they could legally move from place to place within the Empire meant a diminution of the free market in and mobility of labour that had been driving up wages.[6]

After the ebb of the French Empire, newly freed Continental monarchies often retained the Napoleonic systems of control since they were too useful and efficient, as part of domestic surveillance and assisting the authorities to keep track of people who might be a threat to the established order, to abolish.[4]

Starting in 1839, Sultan Mahmud II, impressed by the success of the Napoleonic reforms for building state capabilities, introduced national ID cards to the Ottoman empire in 1844[7] but he was an outlier since relatively few countries would adopt national ID cards until the shock of a World War. [8] National identity cards remained rare in both Europe and the rest of the world throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. [9] There was not much practical need for them and, since paper identity cards without photographs could be easily forged, this made them an unreliable tool for bureaucrats.[10]

Subsequently, the numbers of identity cards issued increased greatly because of advances in photography. Once it became technologically feasible and cost effective to pair a person's identifying documents with their photograph, the efficacy of these documents multiplied.

Fearing the impending battle with Germany for national and Empire survival, lawmakers in the United Kingdom passed the National Registration Act 1939. This mandated that all resident men, women and children carry identity cards at all times.[11]

After the First World War, Germany developed into one of the most democratic, tolerant and liberal nations in Europe. Its welfare, social insurance and national health service were surpassed only by New Zealand. How did the Nazis manage to transform this into totalitarianism?

By establishing a people's registration (Volkskartei - ID card) we will achieve complete supervision of the entire German people.

— Herman Göring, quoted in The Nazi Census – Identification and Control in the Third Reich by Gotz Aly and Karl Heinz Roth, published by Temple University Press, 2004, p. 938

German Jewry did not understand how, but the Reich seemed to be all-knowing as it identified and encircled them and then systematically wrung the dignity from their lives. Indeed, it was clear to the world that somehow the Reich always knew the names even if no one quite understood how it knew the names.

— Edwin Black, in his book IBM and the Holocaust - The Strategic Alliance between Nazi Germany and America's Most Powerful Corporation, Crown Publishers, 2001, p. 125

For the Nazis, the computer system was far more important than the ID card itself[12] but the ubiquitous use of the ID card enabled personal files to be organised in a computerised system, designed to gather and classify information and identify groups of particular interest.

A lot of Germans refused to carry ID cards – Himmler continued to complain about this as late as 1945. A few hours before Adolf Eichmann was executed, a prison warden asked him, "What should the Jews have done? How could they have resisted?"

Eichmann replied "…We would have been at a loss if they had disappeared before being registered… The number of our commandos was very small, and even if the police had helped us with all they had, their chances would have been at least fifty-fifty. …A mass flight would have been disastrous for us." [13]

The few thousand Jews that survived in Germany were predominantly, those who avoided identification by changing address and identity at the time of registration and issue of identity cards. Those who escaped identification and ‘isolation’ in ghettoes generally escaped altogether.

Following defeat in the Battle of France, national identity cards were first issued in France as the carte d'identité des Français under the law of 27 October 1940, and were compulsory for everyone over the age of 16. A central record was also instituted. From 1942, French Jews had the word "Jew" added to their card in red, which helped the Vichy authorities identify 76,000 for deportation as part of the Holocaust.

Under the decree 55-1397 of 22 October 22, 1955[14] a revised non-compulsory card, the carte nationale d'identité (CNI) was introduced, and the central records abandoned. With the introduction of lamination in 1988 it was renamed the carte nationale d’identité sécurisée (CNIS) (secure national identity card). In 1995 the cards were made machine-readable.

Current use

editAlthough there is no longer a general facility for national identity cards to be issued by UK central government to British citizen residents in all parts of Britain, lawful residents[15] of Gibraltar and electors in Northern Ireland can be issued identity cards by the local administrations.

Ireland does not issue national identity cards as such,[16] but on 5 October 2015 it started to issue biometric passports in a handy, credit card sized format.

Norway has decided to start issuing national identity cards from 2016.[17][18]

Identification document

editSmart and secure National Identity Cards have great potential for reducing the costs of governments and making the lives of citizens easier. In the Estonian parliamentary election of 2011, some 140,846 votes were cast electronically representing 24% of the total votes cast.[19] The Estonian ID card was used to authenticate legitimate voters in Estonia's ambitious Internet-based voting programme.

The Estonian Identity Card's chip stores a key pair, allowing users to cryptographically sign digital documents based on principles of public key cryptography using DigiDoc. By 27 May 2014, 160,809,440 electronic signatures had been made - an average of 10 signatures per card holder per year.[20]

The English speaking countries typically lack a tradition of residence registration. The introduction of more systematic identity and registration procedures has often become a matter of great controversy in them and has often been fiercely criticized. Discussion often focuses on the symbolic token of the identity card rather than on the dry details of numbering or the act of registering one’s address. The case of Iceland, however, shows that a personal numbering system, rather than cards or other physical tokens of identity, can be the key feature of how a societyʹs personal identification system is structured.[21][22]

EEA and Swiss citizens exercising their right to free movement in another EEA member state or Switzerland are entitled to use their national identity card as an identification document when dealing not just with government authorities, but also with private sector service providers. For example, where a supermarket in the UK refuses to accept a German national identity card as proof of age when a German citizen attempts to purchase an age-restricted product and insists on the production of a UK-issued passport or driving licence or other identity document, the supermarket would, in effect, be discriminating against this individual on this basis of his/her nationality in the provision of a service, thereby contravening the prohibition in Art 20(2) of Directive 2006/123/EC of discriminatory treatment relating to the nationality of a service recipient in the conditions of access to a service which are made available to the public at large by a service provider.[23]

On 11 June 2014, The Guardian published leaked internal documents from HM Passport Office in the UK which revealed that government officials who dealt with British passport applications sent from overseas treated EU citizen counter-signatories differently depending on their nationality. The leaked internal documents showed that for citizens of Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia and Sweden who acted as a counter-signatory to support the application for a British passport made by someone whom they knew, HM Passport Office would be willing to accept a copy of the counter-signatory's passport or the national identity card.[24] HM Passport Office considered that national identity cards issued to citizens of these member states were acceptable taking into account the 'quality of the identity card design, the rigour of their issuing process, the relatively low level of documented abuse of such documents at UK/Schengen borders and our ability to access samples of such identity cards for comparison purposes'. In contrast, citizens of other EU member states (Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, France, Greece, Italy, Romania and Spain) acting as counter-signatories could only submit a copy of their passport and not their national identity card to prove their identity as national identity cards issued by these member states were deemed by HM Passport Office to be less secure and more susceptible to fraud/forgery. The day following the revelations, on 12 June 2014, the Home Office and HM Passport Office withdrew the leaked internal guidance relating to EU citizen counter-signatories submitting a copy of their national identity card instead of their passport as proof of identity, and all EU citizen counter-signatories are now able only to submit a copy of their passport and not of their national identity card.[25][26]

Travel document

editAs an alternative to presenting a passport, EEA and Swiss citizens are entitled to use a valid national identity card as a travel document to exercise their right of free movement within the European Economic Area and Switzerland.

Strictly speaking, it is not necessary for an EEA or Swiss citizen to possess a valid national identity card or passport to enjoy the right of free movement. In theory, if an EEA or Swiss citizen outside of either the EEA and Switzerland can prove their nationality by any other means (e.g. by presenting an expired national identity card or passport, or a citizenship certificate), they must be permitted to enter the EEA or Switzerland. An EEA or Swiss citizen who is unable to demonstrate their nationality satisfactorily must, nonetheless, be given 'every reasonable opportunity' to obtain the necessary documents or to have them delivered within a reasonable period of time.[27][28][29]

However, when travelling within the Schengen Area or Common Travel Area, other valid identity documentation (such as a driving licence or EHIC card) is often sufficient.[30]

Additionally, EEA and Swiss citizens can enter a number of countries and territories outside the EEA and Switzerland on the strength of their national identity cards alone, without the need to present a passport to the border authorities. (However, Swedish and Finnish law does not allow their own citizens to to leave directly for a non-EEA country or Switzerland without a passport):

A: Unlike Gibraltar, the British overseas territory of Akrotiri and Dhekelia and the British Crown Dependencies of Guernsey, the Isle of Man and Jersey are not part of the European Union. Nonetheless, EEA and Swiss citizens are able to use their national identity cards as travel documents to enter all of these territories.

B: Monaco, San Marino and the Vatican City are de facto parts of the Schengen Area.

C: EEA and Swiss citizens can use their national identity cards when travelling directly between mainland Europe (usually France) and French overseas territories.[46][47][48][48][49][50] In practice, the only French overseas departments/collectivities which can be reached directly by plane from mainland Europe are French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Mayotte and Réunion. In addition, EEA and Swiss citizens can use their national identity cards when travelling within/between French overseas territories (e.g. when flying directly between Guadeloupe and Saint Martin.

D: The national ID card must be in card format.

E: The national ID card must be biometric.

F: Applies only to EU citizens.

G: Applies only to EU citizens and only when travelling on an organised tour entering/exiting at Aqaba airport.

H: Not applicable to nationals of Liechtenstein

J: Except for nationals of: Croatia, France (who are granted the full 6-month visa-free period with an ID card). EFTA nationals using an ID card may only stay for up to 14 days

Turkey allows citizens of Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and Switzerland to enter using a national identity card.[51] Egypt allows citizens of Belgium, France, Germany, Italy and Portugal to enter using a national identity card with a minimum remaining period of validity of 6 months.[52][53] Tunisia allows nationals of Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland to enter using a national identity card if travelling on an organized tour. Dominica, Saint Lucia and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines allow nationals of France to enter using a national identity card. As of March 2016[update], Dominica de facto accepts (at least) German and Swedish ID cards as well. Gambia allows nationals of Belgium to enter using a national ID card.[54] Finally, Greenland allows Nordic citizens to enter with a national identity card (only Sweden and Finland have them, whereas Norway will introduce them in 2016). In practice, all EEA and Swiss citizens can use their ID cards, because no passport control takes place on arrival in Greenland, only by the airline at check-in and the gate, and both Air Greenland and Air Iceland accept any EEA or Swiss ID card.

Difficulties

editAlthough, as a matter of European law, holders of a Swedish national identity card are entitled to use it as a travel document to any European Union member state (regardless of whether it belongs to the Schengen Area or not), Swedish national law did not recognise the card as a valid travel document outside the Schengen Area until July 2015[55] in direct violation of European law. What this meant in practice was that leaving Schengen directly from Sweden (i.e., without making a stopover in another Schengen country) with the card was not possible. This partially changed in July 2015, when travel to non-Schengen countries in the EU (but not others, even if they accept the ID card) was permitted.[56]

Similarly, Finnish citizens cannot leave Finland directly for an EU or EFTA country with only their ID cards.

UK Border Force officials have been known to place extra scrutiny on and to spend longer processing national identity cards issued by certain member states which are deemed to have limited security features and hence more susceptible to tampering/forgery. Unlike their counterparts in the Schengen Area (who, by law, must only perform a 'rapid' and 'straightforward' visual check for signs of falsification and tampering and are not obliged to use technical devices – such as document scanners, UV light and magnifiers – when EEA and Swiss citizens present their passports and/or national identity cards at external border checkpoints),[57] as a matter of policy UKBF officials are required to examine physically all passports and national identity cards presented by EEA and Swiss citizens for signs of forgery and tampering.[58] In addition, unlike their counterparts in the Schengen Area (who, when presented with a passport or national identity card by an EEA or Swiss citizen, are not legally obliged to check it against a database of lost/stolen/invalidated travel documents – and, if they do so, must only perform a 'rapid' and 'straightforward' database check – and may only check to see if the traveller is on a database containing persons of interest on a strictly 'non-systematic' basis where such a threat is 'genuine', 'present' and 'sufficiently serious'),[57] as a matter of policy UKBF officials are required to check every EEA and Swiss citizen and their passport/national identity card against the Warnings Index (WI) database.[58] For this reason, when presented with a non-machine readable identity card, it can take up to four times longer for a UKBF official to process the card as the official has to enter the biographical details of the holder manually into the computer to check against the WI database and, if a large number of possible matches is returned, a different configuration has to be entered to reduce the number of possible matches.[59] For example, at Stansted Airport UKBF officials have been known to take longer to process Italian paper identity cards because they often need to be taken out of plastic wallets,[60] because they are particularly susceptible to forgery/tampering[61] and because, as non-machine readable documents, the holders' biographical details have to be entered manually into the computer.[60]

in 2015, according to statistics published by Frontex[62], the top 6 EU member states whose national identity cards were falsified and detected at external border crossing points of the Schengen Area were Italy, Spain, Belgium, Greece, France and Romania.

Particularly within the Schengen and Hiberno-British[63] travel areas, the active policies of international transport operators rather than the formal requirements of the law have assumed paramount importance. For example, unlike Aer Lingus[64], the largest European carrier, Ryanair demands a passport from British and Irish citizens flying between Dublin and London. Indeed, until 17 June 2014, Ryanair demanded to see a passport even on a purely domestic flight between Belfast and Glasgow.[65] The date of change in Ryanair's conditions of carriage was not entirely coincidental since, also in 2014, a private member's bill was put before the Irish parliament proposing to prohibit transport operators from requiring the production of a passport for travel within the Common Travel Area - but was not passed.[66]

Common design and security features

editOn 13 July 2005, the Justice and Home Affairs Council called on all European Union member states to adopt common designs and security features for national identity cards by December 2005, with detailed standards being laid out as soon as possible thereafter.[67]

Non-EU members, such as the "EFTA four" that nevertheless remain closely associated with the EU, increasingly experience a loss of sovereignty. This erosion happens regardless of the type of EU affiliation and whether a country only has bilateral, static agreements with the EU like Switzerland,[68] or is affiliated through the ever changing and evolving EEA agreements such as Norway, Liechtenstein and Iceland.[69] The loss of sovereignty is not compensated for through participation in the various EU decision-making bodies, as it may be for actual EU member states.[70] These tensions have been exacerbated by the 2015 asylum seekers crisis and it may be that the "border-less" travel area that was Schengen in 2014 will soon be viewed with a nostalgia akin to that of the "passport-less" railway travel area of continental Europe immediately prior to the Great War.[71]

On 4 December 2006, all European Union member states agreed to adopt the following common designs and minimum security standards for national identity cards that were in the draft resolution of 15 November 2006:[72][73]

Material

editThe card can be made with paper core that is laminated on both sides or made entirely of a synthetic substrate.

Biographical data

editThe data on the card shall contain at least: name, gender, birth date, nationality, a photo, signature, card number, start and end date of validity.[74] Some cards contain more information such as height, eye colour, issue place or province, and birth place.

The biographical data on the card is to be machine readable and follow the ICAO specification for Machine-readable travel documents. (However, three European Union member states — Cyprus, Greece and Italy — as well as Gibraltar continue to issue non-machine readable national identity cards.)

Electronic identity cards

editAll EEA electronic identity cards should comply with the ISO/IEC standard 14443. Effectively this means that all these cards should implement electromagnetic coupling between the card and the card reader and, if the specifications are followed, are only capable of being read from proximities of less than 0.1 metres.[75]

They are not the same as the RFID tags often seen in stores and attached to livestock. Neither will they work at the relatively large distances typically seen at US toll booths or automated border crossing channels.[76]

The same ICAO specifications adopted by nearly all European passport booklets (Basic Access Control - BAC) means that miscreants should not be able to read these cards[77] unless they also have physical access to the card.[78] BAC authentication keys derive from the three lines of data printed in the MRZ on the obverse of each TD1 format identity card that begins "I".

According to the ISO 14443 standard, wireless communication with the card reader can not start until the identity card's chip has transmitted a unique identifier. Theoretically an ingenious attacker who has managed to secrete multiple reading devices in a distributed array (eg in arrival hall furniture) could distinguish bearers of MROTDs without having access to the relevant chip files. In concert with other information, this attacker might then be able to produce profiles specific to a a particular card and, consequently its bearer. Defence is a trivial task when most electronic cards make new and randomised UIDs during every session [NH08] to preserve a level of privacy more comparable with contact cards than commercial RFID tags.[79]

The electronic identity cards of Austria, Belgium, Estonia, Finland, Germany,[80] Italy, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Portugal and Spain all have a digital signature application which, upon activation, enables the bearer to authenticate the card using their confidential PIN.[81] Consequently they can, at least theoretically, authenticate documents to satisfy any third party that the document's not been altered after being digitally signed. This application uses a registered certificate in conjunction with public/private key pairs so these enhanced cards do not necessarily have to participate in online transactions.[82]

An unknown number of national European identity cards are issued with different functionalities for authentication while online. Dutch and Swedish national identity cards also have an additional contact chip containing their electronic signature functionality.[83]

Overview of current national identity cards

editMember states issue a variety of national identity cards with differing issuing procedures and technical specifications.[85] Naturally the local names vary (e.g. Personalausweis in German or Dowód osobisty in Polish[86]) in the different languages, but typically translate into English as "IDENTITY CARD" or a close synonym as can clearly be seen if you examine the images of the cards below.

| Territory | Territory, biometric ( ) ? | Reverse of card | Compulsory? | Price | Validity | Issued by? | Latest version | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria |

Identity documentation is optional |

|

|

3 May 2010 | ||||

| Belgium |

National identity card compulsory for Belgian citizens aged 15 or over |

|

|

|

12 Dec 2013 | |||

| Bulgaria [87] |

National identity card compulsory for Bulgarian citizens aged 14 or over |

|

|

The police on behalf of the Ministry of the Interior. | 29 Mar 2010 | |||

| Croatia |

National identity card compulsory for Croatian citizens resident in Croatia aged 18 or over | HRK79.50[88] | 5 years | The police on behalf of the Ministry of the Interior.[89] | 8 Jun 2015 | |||

| Cyprus |

center|frameless|center|upright=0.7 | National identity card compulsory for Cypriot citizens aged 12 or over | €20.00 | 10 years | 24 Feb 2015[90] | |||

| Czech Republic |

National identity card compulsory for Czech citizens over 15 years of age with permanent residency in the Czech Republic |

|

|

Municipality on behalf of the Ministry of the Interior | 19 May 2014 | |||

| Denmark |

No national identity card (See Identity document#Denmark). | |||||||

| — | — | Identity documentation is optional | — | — | — | — | ||

| Estonia |

National identity card compulsory for all Estonian citizens and permanent residents aged 15 or over |

|

5 years | Police and Border Guard Board | 1 Jan 2011 | |||

| Finland |

Identity documentation is optional |

|

5 years | Police | 31 May 2011 | |||

| France |

National identity card optional, however valid government-issued identity documentation is compulsory for all persons |

|

|

|

1 Oct 1994 | |||

| Germany |

Either a national identity card or passport is compulsory for German citizens aged 16 or over and valid identity documentation is compulsory for foreigners |

|

|

City or town of residence | 1 Nov 2010 | |||

| Gibraltar |

Identity documentation is optional, however a national identity card is required for employment | Free of charge |

|

Civil Status and Registration Office, Gibraltar | 8 Dec 2000 | |||

| Greece |

National identity card compulsory for Greek citizens aged 12 or over |

|

15 years | Police | 1 Jul 2010 | |||

| Hungary |

National identity card optional, however a national identity card, passport or driving licence is compulsory for Hungarian citizens aged 14 |

|

|

1 Jan 2016 | ||||

| Iceland | Icelandic state-issued identity cards (nafnskírteini) do not state nationality and consequently are not usable as travel documents in many territories outside of the Nordic countries. | Identity documentation compulsory for all persons 14 years and older [93][94][citation needed] | — | — | — | — | ||

| "Non-nationals" aged 16 years and over must produce identification on demand to any immigration officer or a member of the Garda Síochána (police).[95] | ||||||||

| Ireland | Ireland does not issue[96] and, except for a brief period during the second world war when the Irish Department of External Affairs issued ID Cards to those wishing to travel to the UK,,[97] has never issued national identity cards as such. (On 5 October 2015 it started to issue biometric passports in a handy card format.) | Identity documentation is optional for Irish & British citizens. | ||||||

| Italy (only electronic version, issued in limited parts of Italy) |

Some municipalities issue a new plastic, electronic version | National identity card optional but you must be able to prove identity if stopped by police |

|

|

Town Hall | 1 May 1994 | ||

| Latvia |

National identity card optional but a national identity card or passport compulsory for Latvian citizens aged 15 or over |

|

5 years | Office of Citizenship and Migration Affairs | 1 Apr 2012 | |||

| Liechtenstein |

Identity documentation is optional |

|

|

Immigration and Passport Office, Vaduz | 23 Jun 2008 | |||

| Lithuania |

Identity documentation is optional |

|

1 Jan 2009 | |||||

| Luxembourg |

Luxembourg |

National identity card compulsory for Luxembourg citizens resident in Luxembourg aged 15 or over |

|

1 Jul 2014 [98] | ||||

| Malta |

National identity card compulsory for Maltese citizens aged 18 or over |

|

|

|

12 Feb 2014 | |||

| Netherlands |

Dutch nationals, residing on the Dutch Caribbean islands, although also EU citizens, can only apply for a specific ID card issued by the island's authorities. These cards are not valid for travel in the EEA. | |||||||

| File:New biometroc dutch ID cards, European part of the Netherlands - (Front).png | File:New biometroc dutch ID cards, European part of the Netherlands - (Back).png | National identity card optional, however valid identity documentation is compulsory for all persons aged 14 or over. |

|

9 Oct 2011 | ||||

| Norway |

No national identity card currently, however planned to be introduced in 2016.[103][104] | |||||||

| Identity documentation is optional | Norwegian Police Service | 2016 | ||||||

| Poland |

National identity card compulsory for Polish citizens resident in Poland aged 18 or over | Free of charge |

|

Wójt/Mayor/President of the City | 1 Mar 2015 | |||

| Portugal |

National identity card compulsory for Portuguese citizens aged 6 or over |

|

5 years | Notary and Registry Institute (IRN) | 1 Jun 2009 | |||

| Romania |

National identity card compulsory for Romanian citizens aged 14 or over | RON12 for first or re-issue |

|

Nearest police station | 12 May 2009 | |||

| Slovakia |

National identity card compulsory for Slovak citizens aged 15 or over | Free of charge |

|

1 Dec 2013 | ||||

| Slovenia |

National identity card optional, however a form of ID with photo is compulsory for Slovenian citizens permanently resident in Slovenia aged 18 or over |

|

|

Administrative Unit of the Ministry of Home Affairs | 20 Jun 1998 | |||

| Spain |

National identity card compulsory for Spanish citizens aged 14 or over | €10.60 |

|

Police | 16 Mar 2006 | |||

| Sweden |

Swedish authorities check that Swedes have a passport rather than a Swedish ID card for direct travel from Sweden to a country outside the EU or EFTA even if it accepts the ID card. | |||||||

| Sweden |

Identity documentation is optional for Swedish citizens, however a passport or national identity card is compulsory for alien persons | SEK400 | 5 years | Police | 2 Jan 2012 | |||

| EFTA member state Switzerland is not part of the EEA but, via a series of bilateral agreements, participates in a practical sense. Swiss identity cards can be used to travel inside the EEA and CEFTA areas (except Kosovo) as well as Turkey, and EEA ID cards are accepted by Switzerland. | ||||||||

| Switzerland |

Identity documentation is optional |

|

|

2003 (planned change 2016) | ||||

| United Kingdom | The short-lived UK ID cards were abolished in 2011 by the UK's Identity Documents Act 2010) but Gibraltar identity cards can be issued to Gibraltar residents and Northern Ireland electors can be issued official ID cards | Identity documentation is optional | — | — | — | — | ||

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ In 1988 the government of Ireland announced in the 1989 - 1993 Programme For Government document that it had abandoned plans to establish a national numbering system and ID card. The then Data Protection Commissioner for Ireland, Donal Linehan, had objected vehemently to the proposal at the time it was being proposed. While acknowledging the importance of controlling fraud, the Commissioner observed that the proposal posed "very serious privacy implications for everybody" in the Commissioner's Annual Report for 1991, p.2, 42

- ^ ECB08: What are acceptable travel documents for entry clearance, UK Visas and Immigration. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ^ Manumissio - article by George Long, M.A., Fellow of Trinity College accessed on website of the University of Chicago, 29 March 2016

- ^ a b Allonby, Nathan. 2009. "ID Cards – an Historical View" quoted by Douglas Batson, Al Di Leonardo, Christopher K. Tucker in "Napoleonic Know-How" in an Age of Persistent Engagement

- ^ The Age of Napoleon ISBN 0-313-32014-4 by Susan Punzel Conner, published 2004 by Greenwood Publishing Group, Westport, Connecticut. P.83: "...the livret d'ouvrier - a worker's identity card that laborers were required to present in order to work. So long as workers were employed, the employer kept the livret on file. Workers without livrets or permanent addresses could be arrested as vagabonds and vagrants and jailed. In such a labor environment, workers clamoured for their livrets... Since the revolutionary Le Chapelier Law of 1791 continued to be enforced during the Napoleonic period, labor unrest was at a minimum..."

- ^ Grand Empire: Virtue and Vice in the Napoleonic Era by Walter . Markov, published 1992 by Abbeville Press, New York. Pp: 92-95

- ^ A Brief History of National ID Cards at the website of the François-Xavier Bagnoud Center For Health And Human Rights at Harvard

- ^ Both Australia and Great Britain, for example, introduced the requirement for a photographic passport in 1915 after the so-called Lody spy scandal (see Doulman, Jane, and David Lee (2008). Every Assistance & Protection: A History of the Australian Passport. Federation Press. p. 56. ISBN 9781862876873. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)) - ^ Photographic identification appeared in 1876, (see Hall, Roger, Gordon Dodds, Stanley Triggs (1993). The World of William Notman. David R. Godine. p. 46, 47. ISBN 9780879239398. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)) but did not become widely used until the early 20th century when photographs became part of passports and other ID documents such as driving licences, all of which came to be referred to as "photo IDs" in the US. - ^ Evergreen ID Systems

- ^ A Brief History of National ID Cards at the website of the François-Xavier Bagnoud Center For Health And Human Rights at Harvard gives a wrong date of 1938 and an incorrect title for this piece of legislation

- ^ The Nazi Party: IBM & "Death's Calculator" by Edwin Black

- ^ The Nazi Census – Identification and Control in the Third Reich by Gotz Aly and Karl Heinz Roth, published by Temple University Press, 2004, p. 02

- ^ http://legifrance.gouv.fr/jopdf/common/jo_pdf.jsp?numJO=0&dateJO=19551027&pageDebut=10604&pageFin=&pageCourante=10604

- ^ Security Document World news item of 15 May 2015

- ^ Demography, State and Society: Irish Migration to Britain, 1921-1971 by Enda Delaney, published by Liverpool University Press 2000

- ^ http://norwaytoday.info/home_view.php?id=9975

- ^ 3rd paragraph of page 14 of a briefing paper from the European Migration Network published by the European Commission in 2014

- ^ http://www.vvk.ee/riigikogu-valimised-2011/statistika-2011/e-haaletamise-statistika/

- ^ Estonian ID-card website

- ^ Hallgrímur Snorrason: "Endurskipulagning Þjóðskrár." Lecture at meeting of Skýrslutækni‐félag Íslands, 1 October 1985. Available at [1]

- ^ A short history of national identification numbering in Iceland by Ian Watson in Bifröst Journal of Social Science — 4 (2010)

- ^ http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getAllAnswers.do?reference=E-2014-004933&language=EN

- ^ The Guardian: Passport Office briefing document (11 June 2014) Note that although the list included Switzerland, in practice Swiss citizens would not have been eligible to act as counter-signatories as they are not EU citizens.

- ^ https://www.gov.uk/countersigning-passport-applications

- ^ http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2014/jun/12/ministers-intervene-to-prevent-relaxation-of-rules-in-passport-office

- ^ Article 6.3.2 of the Practical Handbook for Border Guards (C (2006) 5186)

- ^ Judgement of the European Court of Justice of 17 February 2005, Case C 215/03, Salah Oulane vs. Minister voor Vreemdelingenzaken en Integratie ([2])

- ^ [3] Processing British and EEA Passengers without a valid Passport or Travel Document

- ^ Travel documents for EU nationals, europa.eu. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ^ [4]

- ^ [5]

- ^ https://www.geoconsul.gov.ge/HtmlPage/Html/View?id=25&lang=Eng

- ^ https://www.nyidanmark.dk/en-us/coming_to_dk/visa/the_faroe_islands_and_greenland.htm

- ^ https://www.airgreenland.com/help/at-the-airport/check-in

- ^ [6]

- ^ Republic of Macedonia, Ministry of Foreign Affairs official website: Visitors holding national identity cards issued by EU members, or from those countries applying the Schengen acquis, do not need further documentation or visas to enter Macedonia.

- ^ [7]

- ^ http://lex.justice.md/index.php?action=view&view=doc&lang=1&id=359340v (Romanian)

- ^ [8]

- ^ [9]

- ^ [10]

- ^ [11]

- ^ Lov om utlendingers adgang til riket og deres opphold her (utlendingsloven) kap 2 § 15 (Norwegian)

- ^ [12]

- ^ http://www.guyane.cci.fr/fr/aeroport/informations_pratiques

- ^ http://www.guadeloupe.aeroport.fr/guide-du-voyageur/formalites-police-et-douanes.php#formalites-de-police

- ^ a b http://www.aeroport-mayotte.com/gp/Documents-et-Formalites/89

- ^ http://www.martinique.aeroport.fr/Formalites.asp

- ^ http://www.reunion.aeroport.fr/index.php?id=88

- ^ Countries whose citizens are allowed to enter Turkey with their national IDs

- ^ http://www.ibz.rrn.fgov.be/fileadmin/user_upload/CI/eID/fr/acces_etranger/voyager_avec_des_documents_d_identite_belges.pdf

- ^ http://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/fr/conseils-aux-voyageurs/conseils-par-pays/egypte-12239/

- ^ [13]

- ^ Passlag (1978:302) (See 5§) (Swedish)

- ^ Ökade möjligheter att resa inom EU med nationellt identitetskort (Swedish)

- ^ a b Article 7(2) of the Schengen Borders Code (OJ L 105, 13 April 2006, p. 1).

- ^ a b Home Office WI Checking Policy and operational instructions issued in June 2007 (see [14], pg 21)

- ^ See [15], pg 12

- ^ a b See [16], pg 3

- ^ See [17], table of statistics at 4.13 on pg 12

- ^ See [18], table of statistics of fraudulent document detected, by main countries of issuance, 2015 on p. 24

- ^ Irish Independent website accessed 5 December 2015, opinion piece by Kevin Myers: The Hiberno-British dance through time goes on, but it obeys no rules of science or history"

- ^ Aer Lingus website "Travel between Ireland and the UK or UK Domestic travel" accessed 7 December 2015

- ^ Ryanair website "General terms & conditions of carriage" accessed 7 December 2015

- ^ "Houses of the Oireachtas - Freedom of Movement (Common Travel Area) (Travel Documentation) Bill 2014". oireachtas.ie. 2014. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- ^ Council of the European Union: Draft Conclusions of the Representatives of the Governments of the Member States on common minimum security standards for Member States' national identity cards

- ^ Geneva-based researchers Sandra Lavenex and René Schwok writing in "The EU's non-members: independence under hegemony?" edited by Erik O. Eriksen and John Erik Fossum, published by Routledge, 2015

- ^ "The European Unions's non-members: independence under hegemony?" edited by Erik O. Eriksen and John Erik Fossum, published by Routledge, 2015. Chapter 6: The EEA and the case-law of the ECJ: Incorporation without participation? by Halvard Haukeland Fredriksen

- ^ "The EU's non-members: independence under hegemony?" edited by Erik O. Eriksen and John Erik Fossum, published by Routledge, 2015. ISBN: 9781138922457

- ^ "The EU's non-members: independence under hegemony?" edited by Erik O. Eriksen and John Erik Fossum, published by Routledge, 2015. ISBN: 9781138922457. Chapter 12: The United Kingdom, a once and future (?) non-member state by Professor Christopher Lord

- ^ Council of the European Union: Draft Resolution of the Representatives of the Governments of the Member States meeting within the Council on common minimum security standards for Member States’ national identity cards

- ^ List of texts adopted by the Council in the JHA area – 2006

- ^ Machine Readable Travel Documents - Part 5

- ^ HM Government Guide

- ^ [19]

- ^ FIDIS Study on ID Documents

- ^ Privacy Features of European eID Card Specifications Authors: Ingo Naumann, Giles Hogben of the European Network and Information Security Agency (ENISA), Technical Department P.O. Box 1309, 71001 Heraklion, Greece. This article originally appeared in the Elsevier Network Security Newsletter, August 2008, ISSN 1353-4858, pp. 9-13

- ^ Helmbrecht, Udo; Naumann, Ingo (31 January 2011). "8: Overview of European Electronic Identity Cards". In Fumy, Walter; Paeschke, Manfred (eds.). Handbook of eID Security: Concepts, Practical Experiences, Technologies. Vol. II. John Wiley & Sons (published 2011). p. 109. ISBN 978-3-89578-379-1.

- ^ Bundesdruckerei

- ^ Page 110 of the Handbook of eID Security: Concepts, Practical Experiences, Technologies edited by Walter Fumy, Manfred Paeschke and published by John Wiley & Sons

- ^ Helmbrecht, Udo; Naumann, Ingo (31 January 2011). "8: Overview of European Electronic Identity Cards". In Fumy, Walter; Paeschke, Manfred (eds.). Handbook of eID Security: Concepts, Practical Experiences, Technologies. Vol. II. John Wiley & Sons (published 2011). p. 110. ISBN 978-3-89578-379-1.

- ^ Helmbrecht, Udo; Naumann, Ingo (31 January 2011). "8: Overview of European Electronic Identity Cards". In Fumy, Walter; Paeschke, Manfred (eds.). Handbook of eID Security: Concepts, Practical Experiences, Technologies. Vol. II. John Wiley & Sons (published 2011). p. 109. ISBN 978-3-89578-379-1.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|lay-date=and|lay-source=(help) - ^ Sniffing with the Portuguese Identify (sic) Card for fun and Profit by Paul Crocker (Institute of Telecommunications, Covilhã, Portugal), Vasco Nicolau & Simão Melo de Sousa of the Universidade da Beira Interior. Conference paper presented at ECIW'2010 describes "a case study of the re-engineering process used to discover the low-level application protocol data units (APDUs) and their associated significance when used in communications with the Portuguese e-id smart card... primarily done simply to learn the processes involved given the low level of documentation available from the Portuguese government concerning the inner workings of the Citizens Card... also done in order to produce a generic platform for accessing and auditing the Portuguese Citizen Card and for using Match-on-Card biometrics for use in different scenarios... The Portuguese government rolled out a new electronic identity card ... called the "Cartão de Cidadão Português" produced by the "Imprensa Nacional-Casa da Moeda" (INCM www.incm.pt). The initial concept of the card was to merge various identification documents into a single electronic smart card and permit the maximum of interoperability between the various entities whilst following Portuguese law." http://www.researchgate.net/publication/259884617_Sniffing_with_the_Portuguese_Identify_Card_for_fun_and_profit

- ^ State of play concerning the electronic identity cards in the EU Member States (COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, 2010)

- ^ Polish Ministry of the Interior and Administration website page accessed 29 Nov 2015

- ^ http://www.novinite.com/view_news.php?id=108362

- ^ http://www.mup.hr/42.aspx

- ^ Zakon o osobnoj iskaznici (in Croatian)

- ^ The Civil Registry and Migration Department said on Thursday that as of next Tuesday all new ID cards issued to Cypriot citizens would be biometric. News article from Cyprus Mail dated 19 February 2015 accessed 24 February 2015

- ^ https://www.politsei.ee/et/teenused/riigiloivud/riigiloivu-maarad/isikut-toendavad-dokumendid/index.dot

- ^ https://www.poliisi.fi/poliisi/home.nsf/www/serviceprice

- ^ Law put before Icelandic Parliament on 4 March 1965 and passed without controversy as law 25/1965 on 21 April originally featured a minimum age of 12

- ^ "Nafnskírteini afhent þeim sem vilja í næstu viku," Morgunblaðið, 24 June 1965, pp. 2‐3

- ^ Section 12 of the 2004 Immigration Act as amended by section 34 of The Civil Law (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 2011

- ^ In a speech made on 29 May 2003, the then Irish Minister for Justice, McDowell, ruled out the introduction of a national identity card. He further said that such a card, on the continental model, would "irrevocably and irretrievably" alter the relationship between the ordinary person and the police force. "It would make the police the enemy rather than the friend of the people. There are privacy issues and civil liberties issues to be considered," he added.

- ^ Page 117 of Demography, State and Society: Irish Migration to Britain, 1921-1971 by Enda Delaney, published by Liverpool University Press 2000

- ^ https://www.gouvernement.lu/3793755/18-kersch-carte-identite1

- ^ a b [20]

- ^ a b [21]

- ^ Paspoort en identiteitskaart

- ^ Identiteitskaart wordt 10 jaar geldig

- ^ Lover nasjonalt ID-kort i 2015 ([22])

- ^ IKT-satsingen i justissektoren trappes opp ([23])

External links

edit