Suffrage was available to most women and African Americans in New Jersey immediately upon the formation of the state. The first New Jersey state constitution (of 1776) allowed any person who owned a certain value of property to become a voter. In 1790, the state constitution was changed to specify that voters were "he or she". Politicians seeking office deliberately courted women voters who often decided narrow elections. This was so the Democratic-Republican Party had an advantage in the presidential election of 1808.[citation needed]

Under the auspices of election reform, in 1807 a "progressive" law was passed which abolished the property requirement for voting, boosting the number of eligible voters, while explicitly barring women and black voters. The law allowed the Democratic-Republican party to win the state in the 1808 United States presidential election under the new direct electoral system.[1] Like many women in other states, New Jersey women became involved in the abolition movement and several prominent abolitionists who later became suffragists lived in the state. One of the early suffrage protests took place when Lucy Stone refused to pay her property taxes in 1857 under the Revolutionary slogan of "taxation without representation".

After the Civil War, some suffrage groups formed and women began to engage in protest voting. African American women formed separate groups to help push for suffrage in their communities. In the late 1880s, a rural school suffrage bill that affected communities with open meetings, was passed, allowing some women limited access to vote. A series of state court cases were filed on different accounts in regards to voting, further muddying the law. In the early 20th century, suffragists in New Jersey grew in numbers and became bolder. They staged meetings, held parades, and other types of publicity stunts to raise awareness for women's suffrage. Most of the different suffrage groups worked together in cooperatives and pushed for a women's suffrage amendment.

In 1915, they had the change to campaign for a voter referendum on the amendment to the New Jersey state constitution. Despite the hard push, the amendment did not pass. Suffragists continued the fight in the state, with the notable addition of the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (CU), started by New Jersey's Alice Paul. The CU was later known as the National Woman's Party (NWP) and many New Jersey members acted as Silent Sentinels, protesting in Washington, D.C. They were pushing for a federal suffrage amendment which New Jersey ratified on February 10, 1920.

Early history

editSome women enjoyed early suffrage in New Jersey. The state constitution specified that any woman or man who could meet the property requirement set by law could vote.[2] This was a deliberate part of liberal sentiment in the state to allow many different groups of people the right to vote.[3][4][5] New Jersey specifically set the property value low and included African Americans and other groups of people as eligible voters.[3] Married women were not allowed to vote, but widows and unmarried women with property could.[6] The inclusion of women voting early in New Jersey's history was a "radical" effort to extend "Revolutionary doctrine to its furthest—but logical—extreme."[7] A refinement of the original wording specified that voters were considered "he or she," and this change took place in 1790.[8][9]

In 1797, the law was extended to allow women to vote in six New Jersey counties that were not originally included in 1790 change.[10] That year, on October 18, an early women's suffrage poem was published in the Newark Centinel of Freedom.[11] The same paper printed a letter from a state legislator that said that it was intentionally written into the state constitution that all women of all races should have the right to vote.[11] The role of women in the 1800 election of Thomas Jefferson was noticed by the New Jersey press.[11] Alexander Hamilton and Senator Matthias Ogden included women during their campaigning in parts of New Jersey.[12] Many politicians of the time included get out the vote campaigns that also targeted women.[13]

Allowing women to vote remained controversial because some people worried that Revolutionary thought and ideas could go too far.[14] In response to Abigail Adams writing in approval of women voters, her husband, John Adams, wondered "how far Revolutionary principles should be extended."[15] One lawmaker wrote disapprovingly in a newspaper, "Our constitution gives the right to maids and widows, white and black."[8]

Women voters became convenient scapegoats to blame for candidate's losses.[11] Women were sometimes called "petticoat electors" and were considered to be easy to manipulate and generally incompetent.[8] The Federalists also believed that denying women the right to vote would help them politically against the Republicans in New Jersey.[16] Newspapers started reporting that women often decided elections with slim margins.[17] In 1802, it was claimed by the loser of an election that he lost because a "married woman and an enslaved woman had illegally cast ballots."[8]

By studying poll lists, it is estimated that between 1797 and 1807 women made up 7.7% of total recorded votes and in some areas, up to 14%.[8] The True American wrote that women may have made up 25% of the vote in 1802.[13]

Women of the time expressed their political ideas in newspapers, some writing under the names "Mary Meanwell," "Miss Bannerman," and a "Quaker Woman."[18] As women began to vote in greater numbers after 1797, there were more challenges to the right of women to vote.[19] In 1807, there was a tight election that was "hotly contested" because of fraudulent activity where some voters may have voted more than once, with some men even going so far as to dress as women to perpetrate the fraud.[11][20] The men who dressed as women to vote fraudulently were not prosecuted for breaking the law.[21] By this time, women voting were seen as a "political liability rather than a political asset."[5]

The first attempt to take away women's and African-Americans' right to vote was written up in 1802 as "An Act Relating to Female Suffrage" by William Pennington.[22] After some debate, Pennington's act was withdrawn.[23] In 1807, John Condit, who had only won his position by a narrow margin, introduced another act to overturn the right of women and black people to vote in New Jersey.[24] African Americans in Lawnside and Gouldtown continued to agitate against this change, not only immediately after passage, but also in the decades following.[24] Because the statute removed the need for men to prove a property requirement before voting it was "billed as progressive reform."[25] Under the auspices of "election reform" and "anti-corruption," women and black people lost the right to vote.[11][21] There were no challenges to the law by women or African-Americans before the New Jersey constitution was revised.[26] Some white women may have supported the loss of the vote for themselves because it also meant that African-Americans and immigrants could not vote, either.[27] Later, in the 1910s, suffragists argued that stripping the rights of women and black people was done by a "corrupt legislature."[28]

Continued efforts

editDuring the 1830s, many New Jersey women became involved in the abolition movement.[29] Sarah and Angelina Grimké moved with Angelina's husband, Theodore Dwight Weld, to New Jersey in the late 1830s.[30] They met Elizabeth Cady Stanton when she and her husband, Henry Brewster Stanton came to visit.[31] Cady Stanton learned a lot about ongoing reform efforts during this visit.[29]

In 1844, New Jersey wrote a new Constitution which explicitly denied women and African Americans the right to vote.[32] On June 18, 1844, an attempt to include women's suffrage was asked by John C. Ten Eyck, who had a petition from Burlington.[33] The petition was read and not acted on.[33]

By 1847, feminist discussions on married women's property rights were taking place in New Jersey.[34] By 1851, married women were able to receive life insurance benefits.[35] The next year, a limited act to let married women have control over property was passed.[36]

During the Pennsylvania Women's Convention at West Chester in 1852, many New Jersey suffragists attended.[37] John Pierpont spoke about the early rights of New Jersey women to vote during the Women's Rights Convention in Rochester in 1853.[38] A petition for changing the laws of the state to declare that women and men were equal under the law was given to the state legislature by Henry Lafetra, a Monmouth Assemblyman in 1854.[39] The response from the legislature was that women "should accept their subservient role."[39] A few years later in 1857, Harriet Lafetra started another petition from Monmouth County for women's rights and the right to vote, which met with a similar response.[39] In the spring of the same year, Lucy Stone and Henry Browne Blackwell moved to Orange.[39] Stone refused to pay her property taxes that year in November on the grounds that it was "taxation without representation."[39] Because Stone didn't pay her taxes, some of her personal possessions were sold at auction on 1858.[40]

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, women's suffrage activities largely ceased in the state.[41]

After the Civil War

editIn December 1866, Stone and Blackwell encouraged the formation of the Vineland Equal Suffrage Association, which supported both women's and African-American suffrage.[41] The next year, in November, the New Jersey Woman Suffrage Association (NJWSA) was formed in Vineland with Lucy Stone as a leader.[42][43] Vineland was very much a hotbed of political activity at the time.[41] In early 1867, Stone and Antoinette Brown Blackwell created a petition to send to the New Jersey legislature to remove the words "white male" from the voting qualifications in the state constitution.[44] Stone also testified in front of a legislative committee on universal suffrage for both black people and women.[44] Her speech was published and shared throughout the state.[44]

On March 10, 1868, inspired by Stone, Portia Gage attempted to vote.[45] The next November, on the third, 172 women in Vineland, including four black women, attempted to vote.[45] The Vineland ballot box for women was created by teacher and farmer, Susan Pecker Fowler, who made it from blueberry cartons and green fabric.[46] The point of the exercise was to publicize the idea that women did want to vote.[47] Lucy Stone and her mother-in-law also attempted the same thing in Newark.[45] Fowler also wrote the first of around 40 annual letters to the editor in protest of women's disenfranchisement.[45]

After Stone moved to Boston in 1869 the suffrage group she started dissolved.[43][48] During the 1870s, women in New Jersey participated in further protest votes. In 1872, National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) encouraged women to vote to "test the word 'citizen' in the Fourteenth Amendment."[49] Elizabeth Cady Stanton also attempted to vote on November 2, 1880, in Tenafly.[50]

As New Jersey worked to change the state constitution in the 1870s, suffragists petitioned the constitutional convention planning committee to remove the requirement that voters be male.[51] In 1875, the state Constitution was amended to only remove the word "white" from the list of requirements to be a voter.[51] Phebe Hanaford, a Universalist preacher in the state, complained that "At the present time the Constitution of our State is in strict accordance with the statement, viz, that all persons may become voters except lunatics, criminals, idiots, and women."[49]

In the early 1880s, the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) grew in New Jersey, especially among African-American women who formed separate groups and committees.[52] Therese Walling Seabrook worked with the WCTU of New Jersey and helped push it towards affirming women's suffrage.[53] Seabrook worked on the New Jersey WCTU's legislative committee and learned effective strategies for conducting petition drives and lobbying the legislature.[54] In 1884, Seabrook and suffragists Henry Blackwell and Phebe Hanaford began to work together and were able to get some support for women's suffrage from state legislators.[55]

In February 1887, William Miller Baird introduced a bill to allow all people, regardless of race or sex to vote in school meetings.[56] In a surprise move, the New Jersey legislature unanimously passed a rural school suffrage bill in 1887.[49] The new law would only affect women who lived in areas, mostly rural, that voted in open meetings.[57] Cities with formal elections could still block women from voting.[57] In September 1887, Seabrook and Lillie Devereux Blake encouraged women to protest vote in the next election, however it is unknown if any women tried to actually protest vote that year.[58]

In 1890, the New Jersey Woman Suffrage Association (NJWSA) reorganized with the help of Mary Dudley Hussey and elected Judge John Whitehead as the president.[59][60] This group not only advocated for full women's suffrage, but also encouraged women to vote in school elections.[61] They also began to work more closely with the New Jersey WCTU and the New Jersey Grange on suffrage issues.[62]

The state of women's ability to vote in different elections continued to be challenged in the courts in New Jersey. In 1893, a law passed in the state allowed any freeholder, which could include women, the right to vote for local road commissioners.[63] Women's right to vote for the road commissioners was challenged through the case, Allison v. Blake.[64] William Outis Allison who ran for road commissioner and lost, claimed that his opponent, Clinton Hamlin Blake, had won due to illegal voting.[65] Allison claimed that the women's votes were invalid.[65] The Supreme Court of New Jersey ruled in this case on June 11, 1894, that women's votes were "unconstitutional under the 1844 New Jersey Constitution.[64] There were continued efforts to get women out to vote and just as much opposition to women voting in school elections.[66] The state Attorney General, John P. Stockton, issued a formal statement on June 13, 1894, that women's right to vote for school election issues was not affected by the supreme court decision in Allison v. Blake.[66] The case of Kimball v. Hendee took issue with women's votes being rejected during a school election on July 27, 1894, and the courts decided in November 1894 that women voting in school elections was unconstitutional.[67] Landis v. Ashworth was focused on an issue in 1893 were women had voted during a school meeting that included a tax levy.[67] In this case, decided in February 1895, it was decided that women could vote in school meetings for everything except electing school trustees.[67]

The campaign for the 1894 New York constitutional amendment for women's suffrage also had a positive effect on people in New Jersey.[68] NJWSA president, Florence Howe Hall hoped that this ruling might inspire more people to advocate for full women's suffrage in the state.[61] Due to legislators' opposition to full suffrage, NJWSA decided to embark on restoring school suffrage.[61] The year 1895 was the beginning of the New Jersey suffragists' effort to restore women's right to vote in school-related elections.[68] During this year, NJWSA, working with the Jersey City Woman's Club, supported women's right to become lawyers.[61] Their work enabled Mary Philbrook to become the first woman admitted to the New Jersey bar.[61] Later Philbrook became legal counsel to the NJWSA.[61]

In September 1897, the effort to pass the school suffrage bill failed.[61] This slowed down suffrage efforts in New Jersey again.[69]

Reinvigorating the fight

editIn the early 20th century, Harriot Stanton Blatch in New York was able to create a movement of suffragists that included working women.[69] Minola Graham Sexton, who served as president of NJWSA, began to hold suffrage meetings in Ocean Grove in 1902.[70] Sexton also began to give women's suffrage speeches at women's clubs and the New Jersey WCTU, starting in 1904.[71] New Jersey suffragists held a memorial suffrage meeting in Orange in 1906 in honor of the death of Susan B. Anthony.[72] Mina Van Winkle, a friend of Blatch, started the Equality League for Self-Supporting Women of New Jersey (ELSSWNJ) in 1908 which would later be known as the Women's Political Union of New Jersey (WPU).[69][73][74] That same year, Clara Schlee Laddey, a more modern leader took over the NJWSA.[69] In 1909, Emma O. Gantz and Martha Klatschken formed the Progressive Woman Suffrage Society which held the state's first open air meetings.[75]

Sophia Loebinger gave a speech in Palisades Amusement Park in 1909 where she discussed the influence that Native Americans had in suffrage issues and brought three Iroquois people with her.[76] In 1910, Blatch organized a parade in New York City in which New Jersey suffragists also participated.[77] The next year, the parade in New York City was even larger and attracted between 80 and 100 suffragists from New Jersey.[78]

In 1910, the Equal Franchise Society of New Jersey (EFSNJ) was organized in Hoboken with the national founder of the Equal Franchise Society, Katherine Duer Mackay present.[78][79] Around 200 women joined the group.[79] The EFSNJ was made up of prominent and wealthy women living in the state and was based on the New York Equal Franchise League.[80] The New Jersey Men's League for Equal Suffrage also formed in 1910.[78] Lillian Feickert and Miss Pope helped increase the number of members of NJWSA in Jersey City by 1,400 just by canvassing door to door.[81] EFSNJ began a campaign in 1911 to educate women on the importance of equal suffrage.[82]

In November 1911, lawyer, Mary Philbrook, went with a teacher from Newark, Harriet Carpenter, who attempted to register to vote.[83] Philbrook went on to file a case to challenge the "exclusion of women from NJ suffrage."[83] In the case, Carpenter v. Cornish, she argued that the 1844 state constitution "illegally deprived" women of their voting rights in the state.[83] Philbrook took on the case to bring publicity to women's suffrage issues and the case went on to be "highly-publicized."[83] Philbrook's case was rejected on April 11, 1912, by the Supreme Court of New Jersey with the court upholding the limitation on suffrage.[84] The opinion said that "women had not been authorized to vote under the constitution of 1776."[85] The opinion also cited Minor v. Happersett, where the Supreme Court of the United States decided "that the constitution of the United States does not confer the right of suffrage upon anyone."[86]

At the end of 1911, NJWSA and other suffrage groups in New Jersey worked to create a legislative committee.[87][88] A women's suffrage amendment was brought up again in the state legislature in January 1912 by Senator William C. Gebhardt.[83] Gebhardt's daughters were active in the NJWSA and also in the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU).[83] The legislature held a public hearing on the amendment on March 13, 1912.[83][89] There were around six hundred suffragists and anti-suffragists attending the hearing.[83] Working woman, Melilnda Scott, participated in the hearing, marking the first time a prominent labor activist joined the suffragists in New Jersey.[90] Several people, including Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Laddys, Linton Satterthwaite, Rhea Vickers, and Fanny Garrison Villard all testified on behalf of women's suffrage.[91] George Vickers addressed the hearing and said that "No state had ever taken from women the right to vote once it had been given them, excepting New Jersey."[83] The amendment did not pass both houses.[92]

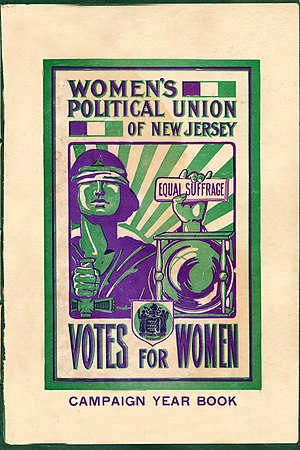

The Equality League, run by Van Winkle, changed their name to the Women's Political Union of New Jersey (WPUNJ) and affiliated with NJWSA in 1912.[92] This group did outreach to Catholic women and working women, including the Women's Trade Union League.[92] Van Winkle included working women including both professionals and blue-collar workers.[93] The WPUNJ had more modern suffrage tactics, planning speeches, suffrage events, and parades.[94] The group planned a "Caravan hike" which toured through 41 different towns throughout New Jersey.[95]

WPUNJ and NJWSA collaborated on a parade that was held on October 26, 1912, in Newark.[96] There were between 800 and 1,000 men and women marching with banners, a band, and a police escort.[96] Antoinette Brown Blackwell participated in the parade and was billed as the "oldest suffragist in the United States."[96] After the parade, Van Winkle headed a mass meeting.[96]

In 1912, Alice Paul became co-chair of the Congressional Committee of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).[97] Paul, who was a Quaker from New Jersey learned militant suffrage tactics in England.[97] She moved to Washington D.C. and rented a basement room to house the NAWSA committee.[98] By April 1913, Paul and Lucy Burns started the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (CU) to lobby for a federal suffrage amendment.[99] NAWSA removed Paul and Burns from the Congressional Committee and the CU became independent.[100] In July 1913, Mabel Vernon spoke throughout New Jersey and helped secure thousands of names for a women's suffrage petition to the U.S. Senate.[101]

During 1913, the New Jersey joint legislative committee for women's suffrage, made up of multiple suffrage groups, continued pressing for a state women's suffrage amendment.[102] In February 1913, a "Votes for Women Special" train left Newark to carry suffrage supporters to Trenton to attend the hearing of the bill.[103] An amendment for women's suffrage passed the New Jersey state legislature in the spring of 1913.[104] However, issues with the wording were discovered on March 27, and so it had to be rewritten and passed again.[105] After this first passage, to become an amendment, it would have to pass again in the next legislative session.[106] It also had to be posted in "designated newspapers" in each county of the state.[106] However, the proposed amendment wasn't published before August 4 when it should have been.[106] This voided the bill and the suffragists would have to try again in the next legislative session.[107] Governor James Fairman Fielder blamed his secretary for forgetting him to send the information to the newspapers on time.[108] The situation enraged many activists.[109]

After the state suffrage convention held in November 1913, a delegation of 75 suffragists met with President-elect Woodrow Wilson, who was the former governor of New Jersey, to request his support of the federal women's suffrage amendment.[110] President Wilson said that "he was giving the matter careful consideration and hoped soon to take a decided stand."[111] On March 3, 1913, Paul organized the Woman Suffrage Procession which drew around 7,000 women to march through Washington, D.C. the day before the inauguration of Woodrow Wilson.[97][112] Later in March, Paul led a delegation of suffragists to meet with the president to support women's suffrage.[98] Wilson said that he hadn't thought much about equal suffrage, but would consider the issue carefully.[98] In mid-November 1913, a delegation of 73 New Jersey activists attempted to meet with the president.[113] Despite getting help from state representative Walter I. McCoy, they were unable to get an appointment with President Wilson.[113] When they weren't able to see him through usual channels, Paul decided they would see the president anyway.[114] The delegation of suffragists marched to the White House where President Wilson did meet with them and talked to them about starting a Suffrage Committee in the House of Representatives.[114][115]

In 1914, NJWSA opened up a new office in Plainfield.[116] Another amendment bill for equal suffrage passed in the state legislature early in the year.[117]

The 1915 campaign

editOn May 6, 1915, the amendment bill was passed a second time.[117] The state suffrage groups created a Cooperative Committee and set up branch headquarters throughout the state.[117] A New Jersey Suffrage Press Committee was organized to send press releases and information to journalists.[118] They also created banners and other forms of advertisement around the state.[118] Elizabeth Colby, leader of the EFSNJ, raised money for the Press Committee.[118] Other forms of publicity included using baseball games to promote suffrage and the usage of a "suffrage camel."[119]

Activists organized their efforts into counties and political districts.[117] Outreach efforts and canvassing took place on a large scale.[117] The WPU didn't limit their outreach to white women and included German-speaking and African American women in their efforts.[117] They also brought in suffrage campaigners to speak to factory workers during lunch.[117] Around 1,000 outdoor meetings were held and an estimated 20,000 pieces of literature were handed out every day.[118] Campaign events were "extensively covered in national magazines and newspapers."[119]

Anna Howard Shaw lobbied President Wilson to support women's suffrage efforts in New Jersey in 1915.[120] John Cotton Dana, W. E. B. Du Bois, Thomas Edison, John Franklin Fort, Theodore Roosevelt, and eventually, President Wilson, came out in support of women's suffrage in New Jersey during this campaign.[121][118][122][123] The State Federation of Labor, however, refused to support the suffrage amendment, and Melinda Scott of the Hat Trimmers Union of Newark refused to affiliate with the state group because of this.[122]

As a publicity stunt, the Suffrage Torch was used in the suffrage campaigns in both New York and New Jersey.[124] The torch was taken around New York and then handed off in middle the Hudson River to Mina Van Winkle of the WPU.[124] Lillian Feickert organized a "Flying Suffrage Squadron."[124] The Squadron toured throughout Middlesex County and held meetings in different locations.[125] New York suffragists also helped the effort, canvassing commuters from New Jersey on the Hudson ferries and conducting get out the vote efforts.[126]

NJWSA held an event on August 13 in Orange to celebrate the birth of Lucy Stone and her tax protest there.[119] Alice Stone Blackwell, John Franklin Fort, and Shaw attended the event.[119] Shaw brought her yellow roadster, Eastern Victory, and drove it in the parade that was held afterwards.[119]

The election was held on October 19, 1915, and had a high voter turnout.[127][128] Some suffragists claimed that anti-suffragists, especially James R. Nugent, had brought in voters from New York to defeat the amendment.[129] Women, including black women served as poll watchers at the majority of the state's polling places.[127] The amendment was defeated by more than 51,000 votes and did especially poorly in urban areas.[130] After the loss of the women's suffrage amendment, Mary Garrett Hay said that "If the women had had a fair vote it would have been wonderful."[131]

The fight continues

editOn December 1, 1915, a chapter of the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (CU) was formed in New Jersey with Alison Turnbull Hopkins serving as the president.[132] The temporary headquarters for the CU were in Morristown.[133] Feickert, involved with the NJWSA, was unhappy that another new suffrage organization had set up in New Jersey.[134] The NJWSA outlined a new direction for the group at its annual convention in January 1916.[127]

In February 1916, the Joint Legislative Committee was able to convince the state legislature to submit a presidential suffrage bill, however, it did not pass the state senate.[130] In 1917, another presidential suffrage bill was introduced, but never made it out of committee.[130] By spring of 1917, the New Jersey State Federation of Women's Clubs (NJSFWC) finally endorsed women's suffrage.[135]

The Eastern Campaign of the CU held a mass meeting in Atlantic City to discuss their opposition towards Democratic members of the government who were blocking the federal suffrage amendment.[136] By March 1917, the CU changed their name to the National Woman's Party (NWP) New Jersey branch.[132] Members of the NWP picketed the White House as "Silent Sentinels."[132] NWP members represented their state on New Jersey Day, picketing the White House as well as participating in a mass picket of around 1,000 women.[137][132]

As the United States voted to enter World War I, NAWSA leaders decided that suffragists would help support the war effort.[138] The NJWSA began to work on patriotic tasks to support the effort in WWI and were the first group to offer their services to the New Jersey governor to help with the war effort.[139][140] Feickert became a vice-chair on the New Jersey Women's Committee of the Council of National Defense where she represented NJSWA.[139] Paul and NWP continued to picket the White House despite the US entry into the war, and emphasized that it was hypocritical to go to war for democracy when women in the US could not vote.[138]

As a federal women's suffrage amendment began to make headway in early 1918 in the United States House of Representatives, NJSFWC resolved to put pressure on President Wilson to influence members of his party to vote for the bill in the United States Senate.[141] In New Jersey, suffragists campaigned for pro-suffrage candidates with some real success.[142] The vote on the federal amendment in the U.S. Senate was lost by only one vote on February 10, 1919, when New Jersey Senator David Baird Sr. voted "no."[142] Eventually, the federal suffrage amendment was passed and waited on ratification by 36 states.[142]

Feickert started chairing a new group, the New Jersey Suffrage Ratification Committee (NJSRC), to fight for the state legislature to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.[143] This group included NJWSA, NJSFWC, the New Jersey Federation of Colored Women's Clubs (NJFCWC), the New Jersey WCTU, and other groups of professional women.[143] The NWP of New Jersey worked to selectively lobby state legislators.[143] Like before, NJSRC used the tactic of supporting pro-suffrage candidates in elections.[143]

In January 1920, the state legislature took up the issue of the federal amendment.[143] It passed the Senate by a large margin on February 2.[143] The debate on the ratification took place in the state assembly on February 9.[143] Suffragists filled the chamber to listen to the debate and early into the night the Assembly passed the resolution on February 10, leading to women celebrating in the halls of the building after the passage.[143][144][145]

Suffragists celebrated the ratification formally on April 23 in Newark, where the NJWSA transitioned into the League of Women Voters of New Jersey.[146]

African-American women suffragists in New Jersey

editIn the early 1880s, African-American women created their own organizations in New Jersey to promote temperance and which were affiliated with the WCTU.[147] During the annual convention in 1887, the New Jersey WCTU voted to support women's suffrage.[147] White members of the Women's Political Unions did outreach to black women in Newark.[117]

W. E. B. Du Bois publicly supported the 1915 New Jersey campaign, writing in The Crisis, "To say the woman is weaker than man is sheer rot: It is the same sort of thing we hear about the 'darker races' and 'lower classes.'"[118] Mary Church Terrell campaigned in New Jersey in October, urging black men to vote for the women's suffrage amendment.[118] During the 1915 election, black women were also part of the poll watching effort.[127] In a New York Times article, the black poll watchers were blamed for losing the women's suffrage amendment in Atlantic County.[148] The paper wrote, "According to responsible citizens, many voted against suffrage for this reason who might have favored the amendment."[148]

Florence Spearing Randolph was involved with getting the New Jersey State Federation of Colored Women's Clubs (NJFCWC) to affiliate with the NJWSA which took place in November 1917.[149][135]

Anti-suffragists in New Jersey

editDuring a testimony on women's suffrage held on March 13, 1912, many anti-suffragists came to testify against equal suffrage.[83] Some the speakers included Harriet White Fisher and Minnie Bronson.[91] The anti-suffragists decided to organize after the hearing, creating the New Jersey Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (NJAOWS) in Trenton on April 14, 1912.[92] The group was an affiliate of the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (NAOWS).[92] The Men's Anti-Suffrage League also opposed suffrage in New Jersey and argued that women did not want the vote.[122] The Dean of Princeton College, William Francis Magie, served as president of the New Jersey Men's Anti-Suffrage League.[150] Magie argued that women's suffrage would disrupt gender roles and "undermine civilization."[150]

Anti-suffragists began to mobilize against the 1915 women's suffrage amendment starting in May 1915.[128] Lillian Feickert, president of the NJWSA accused anti-suffragists of misrepresenting her speech, given in 1915.[151] When the women's suffrage amendment was lost in 1915, anti-suffragists celebrated.[131]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "A New Nation Votes".

- ^ Lewis 2011, p. 1017.

- ^ a b Lewis 2011, p. 1019.

- ^ Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 2.

- ^ a b Klinghoffer & Elkis 1992, p. 162.

- ^ Lewis 2011, p. 1020.

- ^ Lewis 2011, p. 1022.

- ^ a b c d e Schuessler, Jennifer (February 24, 2020). "On the Trail of America's First Women to Vote". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

- ^ Gertzog 1990, p. 49.

- ^ Gertzog 1990, p. 52.

- ^ a b c d e f McGoldrick & Crocco 1993, p. 4.

- ^ Lewis 2011, p. 1025-1026.

- ^ a b Gertzog 1990, p. 53.

- ^ Lewis 2011, p. 1026.

- ^ Lewis 2011, p. 1027-1028.

- ^ Klinghoffer & Elkis 1992, p. 178.

- ^ Lewis 2011, p. 1030.

- ^ Klinghoffer & Elkis 1992, p. 185.

- ^ Lewis 2011, p. 1031.

- ^ Lewis 2011, p. 1031-1032.

- ^ a b Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 4.

- ^ Klinghoffer & Elkis 1992, p. 183.

- ^ Klinghoffer & Elkis 1992, p. 183-184.

- ^ a b McGoldrick & Crocco 1993, p. 5.

- ^ Lewis 2011, p. 1033.

- ^ Klinghoffer & Elkis 1992, p. 189.

- ^ Klinghoffer & Elkis 1992, p. 190-191.

- ^ Gigantino II, James J. (January 22, 2020). "The Curious Memory of Slavery in New Jersey, 1865–1941". New Jersey Studies. 6 (1): 51. doi:10.14713/njs.v6i1.188. ISSN 2374-0647.

- ^ a b Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 5.

- ^ Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 5-6.

- ^ Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 6.

- ^ Dodyk 1997, p. 36-37.

- ^ a b Dodyk 1997, p. 39.

- ^ Dodyk 1997, p. 45.

- ^ Dodyk 1997, p. 46.

- ^ Dodyk 1997, p. 46-47.

- ^ Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 7.

- ^ Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 7-8.

- ^ a b c d e Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 8.

- ^ Dodyk 1997, p. 64.

- ^ a b c Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 10.

- ^ Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 10-11.

- ^ a b Harper 1922, p. 412.

- ^ a b c Dodyk 1997, p. 83.

- ^ a b c d Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 11.

- ^ Getzinger, Diane. "Biographical Sketch of Susan Pecker Fowler". Biographical Database of NAWSA Suffragists, 1890–1920 – via Alexander Street.

- ^ McGoldrick & Crocco 1993, p. 18.

- ^ Michals, Debra (2017). "Lucy Stone". National Women's History Museum. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

- ^ a b c Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 15.

- ^ Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 17.

- ^ a b Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 14.

- ^ Dodyk 1997, p. 200-201.

- ^ Dodyk 1997, p. 202.

- ^ Dodyk 1997, p. 203.

- ^ Dodyk 1997, p. 204.

- ^ Dodyk 1997, p. 208.

- ^ a b Dodyk 1997, p. 209.

- ^ Dodyk 1997, p. 209-210.

- ^ Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 18.

- ^ McGoldrick & Crocco 1993, p. 21.

- ^ a b c d e f g Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 19.

- ^ McGoldrick & Crocco 1993, p. 22.

- ^ Dodyk 1997, p. 245-246.

- ^ a b Dodyk 1997, p. 247.

- ^ a b Dodyk 1997, p. 246-247.

- ^ a b Dodyk 1997, p. 248.

- ^ a b c Dodyk 1997, p. 248-249.

- ^ a b Anthony 1902, p. 821.

- ^ a b c d Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 20.

- ^ Harper 1922, p. 413.

- ^ Harper 1922, p. 414.

- ^ Harper 1922, p. 415.

- ^ "Women's Suffrage in the Early Twentieth Century". On Account of Sex: The Struggle for Women's Suffrage in Middlesex County. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- ^ Perrone 2021, p. 22.

- ^ Harper 1922, p. 416.

- ^ "Amusement Seekers Hear Suffrage Talk". The New York Times. August 15, 1909. p. 35. Retrieved July 11, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 20-21.

- ^ a b c Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 21.

- ^ a b "N.J. Suffragists Are Organized". The Central New Jersey Home News. February 26, 1910. p. 3. Retrieved July 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Dodyk 1997, p. 306.

- ^ Harper 1922, p. 419.

- ^ "Do Women Want the Ballot?". Passaic Daily Herald. October 10, 1911. p. 4. Retrieved July 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 22.

- ^ "Defeating Woman Suffrage in New Jersey". Museum of the American Revolution. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- ^ Vroom 1913, p. 697.

- ^ Vroom 1913, p. 699.

- ^ Dodyk 1997, p. 321.

- ^ "Suffrage Plans in Jersey". Perth Amboy Evening News. January 8, 1912. p. 4. Retrieved July 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "'Votes for Women' Was Their Slogan". The Morning Call. March 13, 1912. p. 6. Retrieved July 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Dodyk 1997, p. 324.

- ^ a b Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 22-23.

- ^ a b c d e Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 23.

- ^ Dodyk 1997, p. 334.

- ^ Dodyk 1997, p. 336.

- ^ Dodyk 1997, p. 337.

- ^ a b c d Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 24.

- ^ a b c McGoldrick & Crocco 1993, p. 28.

- ^ a b c Berberian, Laura. "Research Guides: American Women: Topical Essays: Marching for the Vote: Remembering the Woman Suffrage Parade of 1913". Library of Congress. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- ^ Perrone 2021, p. 31.

- ^ Perrone 2021, p. 31-32.

- ^ Dodyk 1997, p. 357-358.

- ^ Dodyk 1997, p. 341.

- ^ "Special Train for Suffragists". The Montclair Times. February 15, 1913. p. 3. Retrieved July 23, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Dodyk 1997, p. 343.

- ^ Dodyk 1997, p. 343-344.

- ^ a b c Dodyk 1997, p. 344.

- ^ Dodyk 1997, p. 345.

- ^ Harper 1922, p. 432.

- ^ Perrone 2021, p. 30.

- ^ Harper 1922, p. 421-422.

- ^ Harper 1922, p. 422.

- ^ "1913 Woman Suffrage Procession". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- ^ a b Irwin 1921, p. 40.

- ^ a b Irwin 1921, p. 41.

- ^ "Suffragist Ire Up". The Washington Post. November 18, 1913. p. 1. Retrieved August 2, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Suffragists Have New State Office". The Central New Jersey Home News. May 6, 1914. p. 9. Retrieved July 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Perrone 2021, p. 35.

- ^ a b c d e f g Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 35.

- ^ a b c d e Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 34.

- ^ Pusey, Allen (January 2015). "Wilson, Women and War". ABA Journal. Vol. 101, no. 1. Archived from the original on October 25, 2020. Retrieved September 10, 2021.

- ^ "Edison Comes Out Unqalifiedly for Suffrage". Passaic Daily News. October 7, 1915. p. 12. Retrieved August 2, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 37.

- ^ Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 39.

- ^ a b c Perrone 2021, p. 36.

- ^ "Flying Suffrage Squadron Visits New Brunswick". Perth Amboy Evening News. September 20, 1915. p. 8. ISSN 2576-9189. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- ^ Dodyk 1997, p. 387-388.

- ^ a b c d Perrone 2021, p. 40.

- ^ a b "Woman Suffrage Battle Opens in New Jersey As Antis Unlimber Big Guns". The Chatham Press. May 29, 1915. p. 7. Retrieved August 2, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Harper 1922, p. 424-425.

- ^ a b c Perrone 2021, p. 41.

- ^ a b "Suffragists Sad, Antis Jubilant". The New York Times. October 20, 1915. p. 2. Retrieved August 2, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d Perrone 2021, p. 42.

- ^ Dodyk 1997, p. 424.

- ^ Dodyk 1997, p. 425.

- ^ a b Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 47.

- ^ Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 42.

- ^ Irwin 1921, p. 198.

- ^ a b Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 44.

- ^ a b Perrone 2021, p. 43.

- ^ Harper 1922, p. 427.

- ^ Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 50.

- ^ a b c Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 51.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 52.

- ^ "New Jersey and the 19th Amendment". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ "New Jersey Ratification of the 19th Amendment, 1920". New Jersey Women's History. Retrieved August 4, 2021.

- ^ Levin & Dodyk 2020, p. 53.

- ^ a b Perrone 2021, p. 18.

- ^ a b "Negro Women As Watchers". The New York Times. October 20, 1915. p. 2. Retrieved August 2, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Perrone 2021, p. 46.

- ^ a b Mappen, Marc (October 14, 1990). "JERSEYANA". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ "State President Resents Anti Misrepresentation". Passaic Daily News. August 19, 1915. p. 11. Retrieved July 26, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

Sources

edit- Anthony, Susan B. (1902). Anthony, Susan B.; Harper, Ida Husted (eds.). The History of Woman Suffrage. Vol. 4. Indianapolis: The Hollenbeck Press.

- Dodyk, Delight Wing (May 1997). Education and Agitation: The Woman Suffrage Movement in New Jersey (PhD). Rutgers University. ProQuest 304363653 – via ProQuest.

- Gertzog, Irwin N. (1990). "Female Suffrage in New Jersey, 1790-1807" (PDF). In Lynn, Naomi B. (ed.). Women, Politics, and the Constitution. New York: Haworth Press. pp. 47–58. ISBN 9781560240297.

- Harper, Ida Husted (1922). The History of Woman Suffrage. New York: J.J. Little & Ives Company.

- Irwin, Inez Haynes (1921). The Story of the Woman's Party. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company.

- Klinghoffer, Judith Apter; Elkis, Lois (Summer 1992). "'The Petticoat Electors': Women's Suffrage in New Jersey, 1776–1807". Journal of the Early Republic. 12 (2): 159–193. doi:10.2307/3124150. JSTOR 3124150 – via JSTOR.

- Levin, Carol Simon; Dodyk, Delight Wing (March 2020). "Reclaiming Our Voice" (PDF). Garden State Legacy. Susanna Rich. Retrieved June 8, 2021.

- Lewis, Jan Ellen (2011). "Rethinking Women's Suffrage in New Jersey, 1776–1807" (PDF). Rutgers Law Review. 63 (3): 1017–1035.

- McGoldrick, Neale; Crocco, Margaret (1993). Reclaiming Lost Ground: The Struggle for Woman Suffrage in New Jersey (PDF). New Jersey Council for the Humanities. OCLC 29178051.

- Perrone, Fernanda H. (2021). On Account of Sex: The Struggle for Women's Suffrage in Middlesex County (PDF). New Brunswick, New Jersey: Arts Institute of Middlesex County. p. 21.

- Vroom, Garret D. W. (1913). "Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court and, at Law, in the Court of Errors and Appeals of the State of New Jersey". New Jersey Law Reports. 83 (54): 696–704.