Worminghall is a village and civil parish in the Buckinghamshire district of the ceremonial county of Buckinghamshire, England.

| Worminghall | |

|---|---|

SS Peter & Paul parish church | |

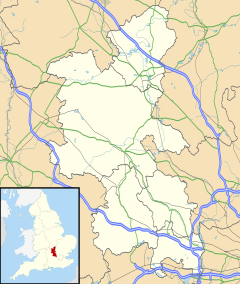

Location within Buckinghamshire | |

| Population | 534 (2011 Census)[1] |

| OS grid reference | SP645085 |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Aylesbury |

| Postcode district | HP18 |

| Dialling code | 01844 |

| Police | Thames Valley |

| Fire | Buckinghamshire |

| Ambulance | South Central |

| UK Parliament | |

The village is beside a brook that forms most of the eastern boundary of the parish. The brook joins the River Thame, which forms the southernmost part of the eastern boundary. The western boundary of the parish also forms part of the county boundary with Oxfordshire. The village is about 4+1⁄2 miles (7 km) west of the Oxfordshire market town of Thame.

The 2011 Census recorded the parish population as 534.[2]

Toponym

editThe Domesday Book of 1086 records the village's toponym as Wermelle.[3] An entry written in 1163 in a pipe roll records it as Wurmehal, and an entry made in 1229 in an episcopal register records it as Wirmehale.[4] Other spellings included Wormehale in the 12th and 13th centuries, Wrmehale in the 13th and 14th centuries, Worminghale in the 14th and 15th centuries and Wornall in the 18th century.[3] "Wornall" (or "Wunnle") are still common local pronunciations.[citation needed]

The toponym is derived from Old English. Halh is a nook or corner of land.[5] Wyrma could be either the name of a man who held the land, or a reference to "worms" living there. In Old and Middle English usage, "worm" could mean reptiles,[4] as in the legend of the Lambton Worm.

J. R. R. Tolkien in his novella Farmer Giles of Ham suggests (tongue-in-cheek) that the 'worm' element in Worminghall derives from the dragon in the story.

Manor

editIn the reign of Edward the Confessor, the manor of Worminghall was part of the estates of his queen, Edith of Wessex.[3] The Domesday Book records that after the Norman conquest of England, Wermelle was assessed at five hides and was one of many manors held by the powerful Norman nobleman Geoffrey de Montbray, Bishop of Coutances.[3] Worminghall became part of the Honour of Gloucester and passed via Hugh de Audley, 1st Earl of Gloucester (1291–1347) and then Margaret de Audley, 2nd Baroness Audley to Hugh de Stafford, 2nd Earl of Stafford (died 1386).[3]

However, Thomas of Woodstock, 1st Duke of Gloucester rebelled against Richard II in 1388. Thomas was attaindered in 1397, and Worminghall was amongst the estates that Thomas forfeited to Henry of Bolingbroke, 3rd Earl of Derby.[3] When Henry father John of Gaunt died in 1399, the Earl was crowned Henry IV of England and Worminghall thus became part of the Duchy of Lancaster.[3] Crown rights to Worminghall appear in a record dating from 1562.[3]

Parish church

editThe Church of England parish church of Saints Peter and Paul is Norman, and the north and south doorways survive from this time.[6] The chancel was built or rebuilt in the 14th century and the bell tower was added in the 15th century.[6] In 1847 the north wall was rebuilt and the present stained glass was inserted in the 15th century[3] east window.[6] The church is a Grade II* listed building.[7]

The tower has a ring of three bells and there is also a Sanctus bell.[3] John Taylor & Co recast all four bells in 1847 at the foundry they had at the time in Oxford.[3]

Saints Peter and Paul's is now part of the Benefice of Worminghall with Ickford, Oakley and Shabbington.[citation needed]

Social and economic history

editWorminghall had a windmill by about 1160 or 1170.[8] A windmill is recorded again in the 14th century, along with a fishery.[3]

The Clifden Arms public house is a timber framed building with brick nogging and a thatched roof.[9] The older part is medieval and the newer wing was added in the 17th century.[9] The pub's current name is more recent, being derived from an 18th or 19th century Viscount Clifden who was heir to the advowson of the parish.[3]

Wood Farm, nearly 2 miles (3 km) west of the village, has a barn that was built in the 17th century or possibly earlier.[10] It is of six bays and is built of rubblestone with ashlar quoins, and was re-roofed in 1779 with a double purlin roof.[10]

John King founded an almshouse charity in 1670 in memory of his father Henry King (1592–1669) who was Bishop of Chichester and a poet.[3] There are ten almshouses, for six old men and four old women.[3] They were built in 1675[6][11] and are now a Grade II* listed building.[11]

A parish school was built in Worminghall in the 19th century. Its Victorian building of polychromatic brick is now the village hall.

RAF Oakley

editRAF Oakley occupied much of the northern part of Worminghall parish from 1942 until 1945. Many of its buildings survive, and those on the south side of the airfield now form the nucleus of a trading estate. This is called Wornal Industrial Park, maintaining the traditional pronunciation and 18th century spelling of the toponym.

Amenities

editReferences

edit- ^ "Key Figures for 2011 Census: Key Statistics". Neighbourhood Statistics: Full Dataset View. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ^ UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Worminghall Parish (E04001557)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Page 1927, pp. 125–130.

- ^ a b Ekwall 1960, Worminghall

- ^ Ekwall 1960, halh

- ^ a b c d Pevsner 1960, p. 301.

- ^ Historic England. "Church of St Peter and Paul (Grade II*) (1158914)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- ^ Reed 1979, p. 135.

- ^ a b Historic England. "Clifden Arms (Grade II) (1311280)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- ^ a b Historic England. "Barn Circa 20 Metres of Wood Farmhouse (Grade II) (1124215)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- ^ a b Historic England. "The Almshouses (Grade II*) (1124253)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- ^ The Clifden Arms

Bibliography

edit- Ekwall, Eilert (1960) [1936]. Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Halh, Worminghall. ISBN 0198691033.

- Page, WH, ed. (1927). "Worminghall". A History of the County of Buckingham. Victoria County History. Vol. IV. London: The St Katherine Press. pp. 125–130.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1960). Buckinghamshire. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. p. 301. ISBN 0-14-071019-1.

- Reed, Michael (1979). Hoskins, WG; Millward, Roy (eds.). The Buckinghamshire Landscape. The Making of the English Landscape. London: Hodder & Stoughton. pp. 135, 194. ISBN 0-340-19044-2.

External links

editMedia related to Worminghall at Wikimedia Commons