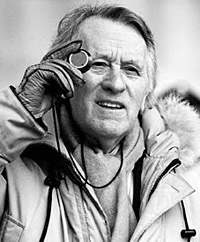

Frederick William Francis BSC[1] (22 December 1917 – 17 March 2007) was an English cinematographer and film director whose filmmaking career spanned over 60 years, from the late 1930s until the late 2000s.[2] One of the most celebrated British cinematographers of his time,[3] he received numerous accolades for his photography, including two Academy Awards and five BAFTA Awards.[4] As a director he was best known for his horror films, notably those made for production companies Amicus and Hammer in the 1960s and 1970s.[5]

Freddie Francis | |

|---|---|

Historical photo of Francis | |

| Born | 22 December 1917 Islington, London, England |

| Died | 17 March 2007 (aged 89) Isleworth, London, England |

| Resting place | Mortlake Crematorium, Kew, London, England |

| Occupation(s) | Cinematographer, film director |

| Years active | 1937–1999 |

| Spouses | Gladys Dorrell

(m. 1940; div. 1961)Pamela Mann (m. 1963) |

Francis started his film career as a cameraman for John Huston and for the directing team of Powell and Pressburger before becoming a cinematographer for notable British films such as Jack Clayton's drama Room at the Top (1959), Jack Cardiff's Sons and Lovers (1960) – which earned him his first Oscar – and the psychological horror film The Innocents (1961). He became well-known for his rich black-and-white CinemaScope framing, and was regarded as one of the top cameraman in the British film industry.[5] He made his directorial debut with the romantic comedy Two and Two Make Six (1962), but gained the most attention for his horror films and thrillers. During the 1960s he was a house director for Hammer Productions, where he made Paranoiac (1963; an early starring vehicle for Oliver Reed), The Evil of Frankenstein (1964), and Dracula Has Risen from the Grave (1968). In the 1970s he worked mainly for Amicus Productions, for which he notably directed the horror anthology Tales from the Crypt (1972).

After nearly two decades as a director, Francis returned to cinematography with The Elephant Man (1980). This established a collaboration with director David Lynch, for whom he also shot Dune (1984), and The Straight Story (1999). He won his second Oscar for the American Civil War film Glory (1989). He also earned acclaim for his work on Karel Reisz's The French Lieutenant's Woman (1981), and Martin Scorsese's Cape Fear (1991).[6]

In addition to his Oscar and BAFTA wins, Francis received an international achievement award from the American Society of Cinematographers in 1997, a lifetime achievement award from the British Society of Cinematographers the same year, and BAFTA's special achievement award in 2004.

Early life

editBorn in Islington in London, England, Francis originally planned to become an engineer. At school, a piece he wrote about films of the future won him a scholarship to the North West London Polytechnic in Kentish Town. He left school at the age of 16, becoming an apprentice to photographer Louis Prothero. Francis stayed with Prothero for six months. In this time they photographed stills for a Stanley Lupino picture made at Associated Talking Pictures (later Ealing Studios). This led to his successively becoming a clapper boy, camera loader and focus puller. He began his career in films at British International Pictures, then moved to British and Dominions. His first film as a clapper boy was The Prisoner of Corbal (1936).

War service

editIn 1939, Francis joined the Army, where he would spend the next seven years. Eventually, he was assigned as cameraman and director to the Army Kinematograph Service at Wembley Studios, where he worked on many training films. About this, Francis said, "Most of the time I was with various film units within the service, so I got quite a bit of experience in all sorts of jobs, including being a cameraman and editing and generally being a jack of all trades."

Career

edit1950–56: Early work

editFollowing his return to civilian life, Francis spent the next ten years working as a camera operator. He quickly became the regular cameraman of The Archers and their cinematographer, Christopher Challis. Francis served as a cameraman on six of The Archers' productions: The Small Back Room, The Elusive Pimpernel (1950), Gone to Earth, The Tales of Hoffmann (1951), Twice Upon a Time, and The Sorcerer's Apprentice. He served as Challis' cameraman on two other films as well: Angels One Five and Affair in Monte Carlo.

Francis was also the regular cameraman of Oswald Morris. His first feature with Morris was Golden Salamander (1950). The two also worked together on Knave of Hearts and three films directed by John Huston: Moulin Rouge, Beat the Devil, and Moby Dick. Francis was given a chance to lead the second unit of Moby Dick and shortly after became a full director of photography on A Hill in Korea (1956), which was shot in Portugal.

1959–68 : British films

editHe subsequently worked on such prestige British dramas such as Room at the Top (1959), Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960), Sons and Lovers (1960), and The Innocents (1961), which he regarded as one of the best films he shot.

For his work on Jack Cardiff's Sons and Lovers he received his first Academy Award for Best Cinematography. The film depicts societal repression in a small coal-mining town during the early 1900s. In the 1961 article of American Cinematographer, the magazine praised his work by stating that the film has "unusual visual beauty and is marked by photographic ingenuity throughout that easily makes it one of the finest monochrome photographic achievements to come along in some time." Cinematographer John Bailey also praised his work saying, "Then I saw Sons and Lovers, and I was knocked out by the poetry and visual beauty of the film. The camerawork was unlike anything I had seen before in an English-language movie."[7]

He next collaborated with director Jack Clayton for the psychological drama film The Innocents starring Deborah Kerr. Francis worked with the CinemaScope aspect ratio. He used colour filters and used the lighting rig to create darkness consuming everything at the edge of the frame. Francis used deep focus and narrowly aimed the lighting towards the centre of the screen.[8] Francis and Clayton framed the film in an unusually bold style, with characters prominent at the edge of the frame and their faces at the centre in profile in some sequences, which, again, created both a sense of intimacy and unease, based on the lack of balance in the image. For many of the interior night scenes, Francis painted the sides of the lenses with black paint to allow for a more intense, "elegiac" focus,[9] and used candles custom-made with four to five wicks twined together to produce more light.

The New Yorker film critic Pauline Kael praised Francis for his work, writing: "I don't know where this cinematographer Freddie Francis sprang from. You may recall that in the last year just about every time a British movie is something to look at, it turns out to be his".[10]

1963–70: Work as a director

editFollowing his Academy Award win for Sons and Lovers, Francis began his career as director of feature films. His first feature as director was Two and Two Make Six (1962). For the next 20-plus years, Francis worked continuously as a director of low-budget films, most of them in the genres of horror or psycho-thriller. Beginning with Paranoiac (1963), Francis made numerous films for Hammer throughout the 1960s and 1970s. These films included thrillers like Nightmare (1964) and Hysteria (1965), as well as monster films such as The Evil of Frankenstein (1964) and Dracula Has Risen from the Grave (1968). On his apparent typecasting as a director of these types of film, Francis said "Horror films have liked me more than I have liked horror films".

Also in the mid-1960s, Francis began an association with Amicus Productions, a company that, like Hammer, specialised in horror pictures. Most of the films he made for Amicus were anthologies, including Dr. Terror's House of Horrors (1965), Torture Garden (1967) and Tales from the Crypt (1972). He also did two films for the short-lived company Tyburn Films; these were The Ghoul and Legend of the Werewolf (both 1975). Francis was more than competent as a director, and his horror films possessed an undeniable visual flair. He regretted that he was seldom able to move beyond genre material as a director. He directed the little-seen Son of Dracula (1974), starring Harry Nilsson in the title role and Ringo Starr as Merlin the Magician. Of the films Francis directed, one of his favorites was Mumsy, Nanny, Sonny, and Girly (1970). Mumsy... is a black comedy about an isolated, upper-class family whose relationships and behaviours lead to deadly consequences. The film was not very well received by mainstream critics but has gone on to become a minor cult favorite among fans. In 1985, Francis directed The Doctor and the Devils, based on the crimes of Burke and Hare.

1980–91: Return to cinematography

editIn 1980 he returned to work as a director of photography, this time for David Lynch in the British drama The Elephant Man (1980). This was principally shot at Wembley Studios in Panavision, using Kodak's Plus X stock — the only monochrome emulsion that met Francis's standards and was available in sufficient quantities. He earned great acclaim for his black-and-white cinematography earning a British Academy Film Award nomination. Ben Kenigsberg of The New York Times dissected Francis's work on the film, writing: "Francis takes advantage of opportunities for high contrast, but note how more subtle elements of Francis’s shading affect the storytelling. Lynch defers a full look at the deformed title character, John Merrick (John Hurt), to milk it for maximum impact. So Francis shows Merrick in varying degrees of shadow for the first half-hour — until a nurse stumbles upon him, at last fully illuminated by a skylight, and screams."[11]

Francis gained a new-found industry and critical respect as a cinematographer. During the 1980s he collaborated with Lynch two more times, with the science fiction film Dune (1984) and the drama The Straight Story (1999), which was shot on location in Iowa in 23 days. One of his favorite camera operators was Gordon Hayman.

He worked on films such as The Executioner's Song (1982), Clara's Heart (1988). Francis's last film as director was 1987's Dark Tower (no relation to the 2004 book of the same name by Stephen King). Francis thought it was a bad picture owing to poor special effects and had his name taken off it. His name was substituted with the name Ken Barnett.

With his work on the Civil War drama Glory (1989) directed by Edward Zwick he earned his second Academy Award. David E. Williams of American Cinematographer wrote, "Francis and director Zwick studied period stills by famed photographer Matthew Brady and others. The stark black-and-white images suggested a realistic approach devoid of filtration or sepia tones, relying instead on the credibility of the locations and production design to simulate the era. Photographically, Francis rendered Glory simply and honestly, with much of the intimate drama revealed in the light and shadow playing upon soldiers’ faces".[12] Francis said of the experience "I’m a great believer in the futility of war and I believe we captured that idea quite well in several parts of Glory. That was always in the back of my mind."

Francis provided the cinematography for the critical favorite The Man in the Moon as well as Martin Scorsese's remake of Cape Fear (both 1991). Francis' suggested that he earned the job working with Scorsese was a recommendation that came from director Michael Powell. Francis again sought to utilize deep focus in order to keep the audience anxiously searching the frame for the psychopathic Max Cady played by Robert De Niro. Francis spoke fondly of his working relationship with Scorsese saying,

"Scorsese is another director who has shot the film in his head before you’ve exposed a single frame of film. You can sometimes talk him into something, though. There was one scene with Bob De Niro where he’s talking on the phone, hanging upside-down from a bar strung across a doorway. I suggested that we start the shot upside down, tight on his face, and then rotate the camera as we tracked backwards so the room would become upside-down. We did that shot with a Panatate remote head, and Marty just fell madly in love with the thing."[12]

Francis' final feature film as a director of photography was a reunion with David Lynch the small intimate drama The Straight Story (1999).

2004–12: Recognition and final years

editFrancis received many industry awards, including, in 1997, an international achievement award from the American Society of Cinematographers, and in 2004, BAFTA's special achievement award. Francis is featured in the book Conversations with Cinematographers (2012) by David A Ellis and published by American publisher Scarecrow Press.

Freddie's final film work was as cinematographer on the music video "Never Ever" by All Saints. It was directed by filmmaker Sean Ellis. The video won best British Video of the Year at the 1998 Brit Awards.

Style and influences

editAs a cinematographer, Francis cited his three mentors as Freddie Young, John Huston, and Michael Powell.[1] His main influences as director were Billy Wilder, William Wyler, and Tod Browning.[13]

Francis' photography favoured black-and-white, though he did work in colour for much of his latter career, and emphasized lighting and framing over colour schemes. In an interview with The Guardian, Francis said "I still photograph things in black and white, but the fact that it's colour stock means they come out in colour. I know that sounds rather facetious ... but I prefer to think in terms of light and shade than in colour."[1]

Director Martin Scorsese, who worked with Francis on Cape Fear, cited Francis's use of a gothic atmosphere.[1] "He understands the obligatory scene of a young maiden with a candle walking down a long hall towards a door. 'Don't go in that door!' you yell, and she goes in! Every time, she goes in! So I say to him, 'This has to look like The Hall,' and he understands that."[1]

Personal life

editFrancis married Gladys Dorrell in 1940, with whom he had a son; in 1963 he married Pamela Mann-Francis, with whom he had a daughter and a second son.

Francis died, aged 89, from the lingering effects of a stroke.

Filmography

editCinematographer

editFilm

TV series

| Year | Title | Director | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1961 | The Magical World of Disney | William Fairchild | Episode "The Horsemasters" |

TV movies

| Year | Title | Director | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1982 | The Executioner's Song | Lawrence Schiller | |

| 1989 | Peter Cushing: One Way Ticket to Hollywood | Alan J. W. Bell | Documentary film |

| 1990 | The Plot to Kill Hitler | Lawrence Schiller | |

| 1993 | A Life in the Theatre | Gregory Mosher |

Director

editFilm

edit| Year | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1962 | Two and Two Make Six | |

| The Brain | ||

| 1963 | The Day of the Triffids | Uncredited |

| Paranoiac | ||

| 1964 | Nightmare | |

| The Evil of Frankenstein | ||

| Traitor's Gate | ||

| 1965 | Dr. Terror's House of Horrors | |

| Hysteria | ||

| The Skull | ||

| 1966 | The Psychopath | |

| 1967 | The Deadly Bees | |

| They Came from Beyond Space | ||

| Torture Garden | ||

| 1968 | Dracula Has Risen from the Grave | |

| The Intrepid Mr. Twigg | Short film | |

| 1970 | Mumsy, Nanny, Sonny and Girly | |

| Trog | ||

| 1971 | The Vampire Happening | |

| 1972 | Tales from the Crypt | |

| 1973 | The Creeping Flesh | |

| Tales That Witness Madness | ||

| 1974 | Son of Dracula | |

| Craze | ||

| 1975 | The Ghoul | |

| Legend of the Werewolf | ||

| 1977 | Golden Rendezvous | Uncredited |

| 1985 | The Doctor and the Devils | |

| 1987 | Dark Tower | Co-directed with Ken Wiederhorn; Collectively credited as "Ken Barnett" |

Writer (Credited as "Ken Barnett")

- Diary of a Bachelor (1964)

- What Waits Below (1984) (Story only)

Television

edit| Year | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1967-1868 | Man in a Suitcase | 4 episodes |

| 1967-1969 | The Saint | 2 episodes |

| 1969 | The Champions | Episode "Shadow of the Panther" |

| 1973-1974 | The Adventures of Black Beauty | 5 episodes |

| 1974 | CBS Children's Film Festival | Episode "A Member of the Family" |

| 1976 | Star Maidens | 5 episodes |

| 1979 | Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson | 4 episodes |

| 1996 | Tales from the Crypt | Episode "Last Respects" |

Awards and nominations

editAcademy Awards

| Year | Category | Title | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 | Best Cinematography | Sons and Lovers | Won |

| 1989 | Glory | Won |

BAFTA Awards

| Year | Category | Title | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | Best Cinematography | The Elephant Man | Nominated |

| 1981 | The French Lieutenant's Woman | Nominated | |

| 1989 | Glory | Nominated | |

| 1991 | Cape Fear | Nominated |

References

edit- ^ a b c d e "BSC Members | British Society of Cinematographers". bscine.com. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ "Francis, Frederick William [Freddie] (1917–2007), cinematographer and film director". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/98649. Retrieved 31 October 2020. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "Cinematic Glory: Freddie Francis, BSC". The American Society of Cinematographers. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ "Freddie Francis | British cinematographer and director". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ a b "Freddie Francis: 10 essential films". BFI. 22 December 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ "Freddie Francis: 10 essential films". BFI. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ "Cinematic Glory". American Cinematographer. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ^ Landis 2011, p. 110.

- ^ Hogan 2016, p. 87.

- ^ "Freddie Francis on The Innocents". Criterion Collection. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ^ Kenigsberg, Ben (16 July 2020). "Do Cinematographers Have a Signature? Let's Try a Test". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ^ a b "Cinematic Glory: Freddie Francis, BSC". American Cinematographer. 30 December 2021.

- ^ Lindbergs, Kimberly (21 March 2007). "R.I.P. Freddie Francis 1917–2007". CINEBEATS. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

Sources

edit- Freddie Francis: The Straight Story from Moby Dick to Glory, a Memoir - Freddie Francis (with Tony Dalton), Scarecrow Press, 2013.

- The Films of Freddie Francis – Wheeler Winston Dixon, Scarecrow Press, 1991. ISBN 0-8108-2358-6 (hardcover)

- The Men Who Made The Monsters – Paul M. Jensen, published 1996 – ISBN 0-8057-9338-0 (paperback)

- Hogan, David J. (2016). Dark Romance: Sexuality in the Horror Film. McFarland Classics. ISBN 978-0-786-46248-3.

- Landis, John (2011). Monsters in the Movies. New York: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-756-68846-2.

External links

edit- Freddie Francis The British Entertainment History Project

- Freddie Francis at IMDb

- Freddie Francis biography on (re)Search my Trash